|

| Athens, NAM Roman, Antonine, Osteotheke. Yes, this marble osteotheke is a millennium, more or less, earlier than this Post, but see the remarks below on the ivory Veroli casket. |

MIDDLE BYZANTINE AND ROMANESQUE

Middle

Byzantine art is the art of the Macedonian and Commenian dynasties at

Constantinople. It began with the

end of iconoclasm in the Macedonian dynasty and is part of a great revival of

scholarship and literature called the Macedonian Renascence, in art often

called the Second Golden Age of Byzantine Art, Justinian's century being the

First. It is punctuated by the

rise of Venice and the First Crusade (1095-1099) and terminated in 1204 by the

Fourth Crusade's sacking Constantinople (illustrating the difficulty of

controlling an army at a distance with anything less than present-day

communications). That the

Macedonian Renascence tried to recapture the values of Greek civilization as

well as its prose style and grammar and, in art, some of its imagery, is

apparent in their attitude to the classics of Greek literature, such as

Athenian drama, as well as in the profound humanism that pervades Christian

Middle Byzantine imagery, preeminently in the great mosaics in the monastic

church at Daphnê, just outside Athens.

Despite the difficulties of travel, and even before the first crusade,

western Europe was hardly unaware of Byzantine culture; after that crusade a

trickle became a flood. But the

great new architecture of the late eleventh and early twelfth centuries shows

closer acquaintance with Islamic architecture than with Byzantine, except in

Venice where San Marco is practically a Byzantine church and in parts of

southern France (at Périgueux); it is not that they travelled to Damascus or

Baghdad or even to north Africa, but that southern Spain had remained Moslem

until c. 1085 A.D., and they did know the great mosque at Cordoba.

The term

"Romanesque" that we use to designate European art beginning in the

second half of the eleventh century really refers to what happened in

architecture and sculpture all over Europe; there is no comparable revolution

in book illustration or other kinds of painting, although the styles certainly

are different from earlier ones.

The revolution in architecture is in reviving vaulted ashlar stone

building on a scale to rival ancient Rome. Since southern France and the German Rhineland had been part

of the ancient Roman empire, those regions had very impressive examples of

Roman building, especially in towns like Trier and Arles, just to name

two. Now, in Rome itself, where

they had access to volcanically formed hydraulic cement, the vaulting of

buildings had been done in concrete (see the Basilica of Constantine and the

Pantheon and the Great Hall of Trajan's Markets in your Prints). But Europe north of the Alps, while

possessing fine stone, had no such cement for making concrete (neither had the

Greek East, which is why Byzantine domes are of stone or brick). In France and the Rhineland, the

ancient Roman buildings had stone vaults, and as much of the mason's

traditional craft as survived was in building with stone. Of course, a number of persons did go

to Rome; they knew about the ancient structures there, but when they turned to

emulating and competing with Roman glory in architecture, architects north of

the Alps created a Roman-ish revival using their own materials.

Each region

(not necessarily coinciding with the boundaries of modern nations) had its own

building traditions. Each vied in

the effort of "revival" (actually producing original architectural

forms), but all that the various styles of the different regions share is their

Romanishness, so that Romanesque is a perfect label. Much the same is true of the different regional styles of

architectural sculpture (to be discussed with slides).

It is

inappropriate and futile to try to find any other embracing formula for

"what is Romanesque?".

For example, it is not the "round arched" period, because in

Burgundy pointed arches are used in Romanesque. It is not even true that all the churches are vaulted; in

Tuscany otherwise advanced church design has wooden roofs. They are not less Roman-ish for that

reason; the Italians knew best of all that Roman basilicas were

wooden-roofed. It is not

meaningful to ask which region is more progressive than another. Cluniac, Pilgrimage, Norman,

Anglo-Norman, Rhineland, Lombard, and Tuscan are only some of the richly varied

architectural types within Romanesque.

The first three works that we consider here

are contemporary with Ottonian art in the West, but while the latter is usually

included under "Early Medieval Art", in the Greek-speaking world the

art of the 10th and early 11th centuries goes under our "Middle

Byzantine" heading, although, as we have noted, this period is punctuated

by the events of the First Crusade at about the chronological point where we

regard "Romanesque Art" in the West as beginning.

[K 148]

[1606] The book called the Paris Psalter (because it is in the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris),

like certain Byzantine literary works of the same period, is more egregiously

"Classical" (i.e., Greco-Roman, since by the 10th century all

of pagan antiquity seemed "Classical" to them) than anything we have

seen for some time. The framed,

full-color illustrations are full of carefully labelled personifications (Melodia, the Red Sea, with an oar over

her shoulder, Bethlehem). The rocks and trees look almost like

something from Pompeii. The

modelling in light and dark is more purposeful than in the Carolingian

Coronation Gospels; the 3/4 views (and even the foreshortened shoulders) are

rather convincing, while the adorable animals listening to David's harp (as is

he were Orpheus! Both David and

Orpheus have come to be regarded as antetypes of Christ) and the lunging horses

in the Crossing of the Red Sea put us back in a world wholly different from

that of symbolic, stylized animals.

In the latter scene, we have again the flying cape with its end lifted by

some invisible wind that we saw in the Vienna Genesis (in fact, the 6th-century

Genesis has a scene of Noah's Flood as full of naturalism as this Crossing of

the Red Sea). Even more remarkable

is the presence of Mood and Sentiment: I mean, the whole of the David picture

is imbued with idyllic feeling, and the whole of the Red Sea picture

is dramatic--not just the features of individual figures. Equally important and impressive is the

indication of atmospheric distance (with the distant trees and buildings

becoming paler and brighter as well as smaller) in the David picture. All these characteristics indicate that

the learned segment of the Byzantine world still possessed ancient illustrated

books, early enough to have served as models for the Paris Psalter, a prime

document of the Macedonian Renascence (we save the French spelling,

Renaissance, for the 15th and 16th centuries). On the other hand, the frames of these pictures are

wholly anti-classical in character: they are painted imitations of enamel work

and jewels in gold settings, unlike the acanthus frames we saw in the

Carolingian manuscripts. The

Middle Ages loved to set ancient treasures, such as Roman cameos, in rich,

bejewelled settings, and books of the Gospels had heavily jewel-encrusted covers. These pictures look like ancient images

set in "barbarian" frames: recall the Germanic pins that we

studied. Most Byzantine jewelry is

just as "medieval" as that of the west.

[K 19] [K 20] The Harbaville Triptych, ca. A.D. 1000 (to correct the dates on the Prints) is one of the finest Middle Byzantine ivories. A triptych, of course, differs from a diptych in being threefold, but also it is not writing tablets, rather a portable divine image whose outer leaves close. When closed, you see the cross with trees (recall Sigvald's Balustrade at Cividale) on the back (the inscription is IC XC NI-KA: Jesus Christ Conquers) and on the leaves 8 full-length saints and 4 saints' busts in circles. When open, you see it as in [K 19]. The four soldier saints are George, Eustathios, and the two Theodores. St. John the Theologian (i.e., the Evangelist, not the Baptist) and St. Andrew accompany SS. Peter and Paul below the figure of Christ enthroned; the entreating figures left and right of Christ are Mary, his mother, and John the Forerunner (i.e., the Baptist). This composition of Mary and John interceding with Christ for believers is called a Deësis, which is Greek for "intercessory prayer". Here, then, the subject matter is as Christian as can be, and the attenuation of bodily substance to suggest spirituality that we have noted before is especially obvious here. But, to the contrary, the style of the figures, and especially of their drapery in relation to their bodies, shows once again how Byzantine artists have not lost the Greek sense of structural logic: the drapery wraps around and continues, it falls in accord with gravity, it folds reasonably, and, even if the bodies seem to be made of stuff more rarified than flesh, the drapery obeys the stance of the body. In sum, the artist is not thinking of drapery as a pattern but in terms of the cloth (being one thing) in relation to a figure (which is another).

[K 300] The Veroli Casket offers

another contrast. This is the kind

of Middle Byzantine secular luxury art probably destined for wealthy young

women of marriageable age. So it

bears famous stories about girls: Iphigeneia and Europa. The workmanship is excellent. The style is utterly different from

that of the Harbaville Triptych, doubtless because it both has different

prototypes and also may have been made in a workshop with a different ancestry

of successive apprenticeships. The

dichotomy is astonishing: the subject matter and even the compositions are from

ancient classical sources, with no hint of Christian content since this is a

secular piece, but the short-bodied, knobby, almost funny (but very skillful)

style seems to us hilariously un-Classical. We wonder, how did it seem to them? Did they really look at this style as,

somehow, the way ancient literature was supposed to look? That is why Byzantine art is so richly

fascinating: this is the civilization that inherits and preserves alive, both

together, Christianity in the language of the Gospels, in the world where the

evangelists mostly moved, and Greek language, history, and art and

literature, from their own unbroken past.

Many considerations have been brought to bear on the style of the Veroli

casket (and other ivories resembling it): the use of drills, reinterpreting in

ivory a style in book illustration, reinterpreting in ivory the style of

certain late Roman-Empire marble sarcophagi.

The Antonine osteotheke (for the collected bones of a corpse) is just as atypical of Antonine styles of the 2nd c. AD as the Veroli Casket is of a date c. 1,000 AD. The casket is much more painstaking work. In any case, the Antonine work could not itself be a model for the Byzantine piece. Not only is their manner, however unmistakably related but they share several stories and compositions, favorites from Greek literature, such as Iphigeneia and Jason and Europa and an Aphrodite in the Capua/deMilo pose (and with Eros at her feet). We are forcibly reminded of how many illustrated books existed that have been lost, as also, in a different way, we are with the Paris Psalter.

The Antonine osteotheke (for the collected bones of a corpse) is just as atypical of Antonine styles of the 2nd c. AD as the Veroli Casket is of a date c. 1,000 AD. The casket is much more painstaking work. In any case, the Antonine work could not itself be a model for the Byzantine piece. Not only is their manner, however unmistakably related but they share several stories and compositions, favorites from Greek literature, such as Iphigeneia and Jason and Europa and an Aphrodite in the Capua/deMilo pose (and with Eros at her feet). We are forcibly reminded of how many illustrated books existed that have been lost, as also, in a different way, we are with the Paris Psalter.

[G 199] Venice did not need to go on Crusade to

learn about the Byzantine world; having control of the Dalmatian coast (most of

Croatia), Venice ruled the Adriatic at this period and not only traded with but

was under Byzantine political influence.

Yet the Church of San Marco,

begun in 1063, although so Byzantine-like that some call it

"Byzantine", is rather broader-proportioned than contemporary Eastern

churches. Its plan is different

from Hagia Sophia's, though it is nearly equally grand: it is a cross inscribed

in a square, each arm of the cross also being square, and a dome is raised over

each of the arm squares as well as over the center, none of the domes singly

being as vast as Hagia Sophia's.

Like the Roman Pantheon's, its domes are not concealed by roofs but

covered with gilded copper over wood (in the Pantheon, it was originally bronze

over the concrete dome). The

general effect of the figured mosaics, on a gold ground, recalls Byzantine

mosaic, but their styles (from several centuries) are rather different.

Now we turn to the Romanesque art of Western

Europe

CLUNIAC CHURCH

DESIGN

[MG 268] [MG 29] [K 31] The Abbey Church and Monastery of Cluny was the most powerful Benedictine Abbey throughout the Middle Ages; the Benedictine Order, too, was international, and sometimes the Abbot of Cluny told the Pope what to do. The architecture and sculpture of Cluny and of the churches of her daughter houses (priories) are among the most important and influential of the Romanesque styles.

You cannot fail to notice the general resemblance of the plan of the monastery to St. Gall and Centula, since all three are Benedictine (if you have read Umberto Eco's novel, The Name of the Rose, you will know that a 14th-century abbey in Italy also was laid out similarly). By the late 11th century, Cluny had already outgrown two abbey churches. Cluny III, which you see in the Plan and in Kenneth J. Conant's fine drawing, stood until the French Revolution; today one end of one transept survives. Let us read the plan: it is 5-aisled with two transepts; apsidal chapels emerge to the east from the arms of the transepts, and five apsidal chapels radiate from the apse; beyond the choir, a ring of columns separates the apse, proper, from the ambulatory (Latin for "walk-around") that wraps around it. Now let us read the drawing which is a view from the east: low down we see the nine low chapels, on the eastern transept and around the apse; next highest we see the wall and windows of the ambulatory; next highest, then, is the clerestory of the apse and the roofs, to left and right, of the arms of the eastern transept; higher, we see the end wall of the choir above the half-dome of the apse, which is level with the roofs of the nave and the taller western transept, and we see that the promise of multiple towers seen in the Carolingian and Ottonian churches is fulfilled in Romanesque: three matching octagonal towers over the crossing of the western transept and nave and over the ends of the western transept. An architectural drawing, even one that looks like a picture, to be studied must be read, even as we have just done. What is not visible in these drawings is that inside Cluny III's nave was vaulted, with a slightly pointed barrel vault, reinforced at every support (pier) in the nave by a stout, slightly pointed transverse arch. A pointed arch is double-centered: its lines are arcs drawn from two centers, intersecting at the point. We think the idea was borrowed from Islamic building practice. On the wall of the nave, below the clerestory and above the arcade (the nave-wall arcade also had slightly pointed arches), was a "blind" arcade called a triforium; it is called blind because it has no light behind it. All of this is in ashlar stone; stone is the native building material of the Rhône basin and was so even during the Roman Empire, but medieval builders heretofore had seldom ventured to emulate their ancestors' Roman vaulting. Note that this is not dry-stone ashlar, like Greek and Egyptian, but mortared ashlar.

The capitals of the columns separating the apse from the ambulatory, completed ca. 1095, are figured. Sometimes, for example in the Baths of Caracalla, the Romans put figures in Composite capitals; those are the ancestors of these, which still might be called "Composite", but the figural decoration now is much more important. Now several centers in Europe are having their own Renascence of learning (not just the Macedonian Dynasty in Constantinople), to which the Cluny capitals are eloquent testimony. The figures represent not only human labors, like Agriculture, but the fields of basic and more advanced learning, the Trivium and the Quadrivium, and the musical Modes (the transposable scales that we call Keys had not yet been devised). We are forcibly reminded that the abbeys were great centers of learning and music; learning and plainsong are the opus dei (work of God), at least as much as agriculture, since the latter can be done for profit. Especially characteristic of the heads of these Cluny sculptures are the close-set drilled eyes, the neatly combed, center-parted hair, the rather pursed lips of the mouths, and the carefully designed drapery folds, flattened and neatly arranged one on top of the other. Now we have the revival of architectural sculpture on a large scale. The artists must have had recourse to book illustrations and small sculptures, such as ivories, to re-create major sculpture "overnight".

In summary, a Cluny type church has an ambulatory with radiating chapels around its main apse; it has slightly pointed arches (let no one tell you that pointed = Gothic); it has a clerestory and a triforium.

[MG 268] [MG 29] [K 31] The Abbey Church and Monastery of Cluny was the most powerful Benedictine Abbey throughout the Middle Ages; the Benedictine Order, too, was international, and sometimes the Abbot of Cluny told the Pope what to do. The architecture and sculpture of Cluny and of the churches of her daughter houses (priories) are among the most important and influential of the Romanesque styles.

You cannot fail to notice the general resemblance of the plan of the monastery to St. Gall and Centula, since all three are Benedictine (if you have read Umberto Eco's novel, The Name of the Rose, you will know that a 14th-century abbey in Italy also was laid out similarly). By the late 11th century, Cluny had already outgrown two abbey churches. Cluny III, which you see in the Plan and in Kenneth J. Conant's fine drawing, stood until the French Revolution; today one end of one transept survives. Let us read the plan: it is 5-aisled with two transepts; apsidal chapels emerge to the east from the arms of the transepts, and five apsidal chapels radiate from the apse; beyond the choir, a ring of columns separates the apse, proper, from the ambulatory (Latin for "walk-around") that wraps around it. Now let us read the drawing which is a view from the east: low down we see the nine low chapels, on the eastern transept and around the apse; next highest we see the wall and windows of the ambulatory; next highest, then, is the clerestory of the apse and the roofs, to left and right, of the arms of the eastern transept; higher, we see the end wall of the choir above the half-dome of the apse, which is level with the roofs of the nave and the taller western transept, and we see that the promise of multiple towers seen in the Carolingian and Ottonian churches is fulfilled in Romanesque: three matching octagonal towers over the crossing of the western transept and nave and over the ends of the western transept. An architectural drawing, even one that looks like a picture, to be studied must be read, even as we have just done. What is not visible in these drawings is that inside Cluny III's nave was vaulted, with a slightly pointed barrel vault, reinforced at every support (pier) in the nave by a stout, slightly pointed transverse arch. A pointed arch is double-centered: its lines are arcs drawn from two centers, intersecting at the point. We think the idea was borrowed from Islamic building practice. On the wall of the nave, below the clerestory and above the arcade (the nave-wall arcade also had slightly pointed arches), was a "blind" arcade called a triforium; it is called blind because it has no light behind it. All of this is in ashlar stone; stone is the native building material of the Rhône basin and was so even during the Roman Empire, but medieval builders heretofore had seldom ventured to emulate their ancestors' Roman vaulting. Note that this is not dry-stone ashlar, like Greek and Egyptian, but mortared ashlar.

The capitals of the columns separating the apse from the ambulatory, completed ca. 1095, are figured. Sometimes, for example in the Baths of Caracalla, the Romans put figures in Composite capitals; those are the ancestors of these, which still might be called "Composite", but the figural decoration now is much more important. Now several centers in Europe are having their own Renascence of learning (not just the Macedonian Dynasty in Constantinople), to which the Cluny capitals are eloquent testimony. The figures represent not only human labors, like Agriculture, but the fields of basic and more advanced learning, the Trivium and the Quadrivium, and the musical Modes (the transposable scales that we call Keys had not yet been devised). We are forcibly reminded that the abbeys were great centers of learning and music; learning and plainsong are the opus dei (work of God), at least as much as agriculture, since the latter can be done for profit. Especially characteristic of the heads of these Cluny sculptures are the close-set drilled eyes, the neatly combed, center-parted hair, the rather pursed lips of the mouths, and the carefully designed drapery folds, flattened and neatly arranged one on top of the other. Now we have the revival of architectural sculpture on a large scale. The artists must have had recourse to book illustrations and small sculptures, such as ivories, to re-create major sculpture "overnight".

In summary, a Cluny type church has an ambulatory with radiating chapels around its main apse; it has slightly pointed arches (let no one tell you that pointed = Gothic); it has a clerestory and a triforium.

[G 255] [K 51] The Cathedral of St. Lazare at Autun, a little north of Cluny, proves that the type of the Cluny nave was not confined to monastic churches, since a Cathedral is by definition the principal church of a major town and the seat (cathedra) of a bishop, whereas a monastic church, by definition, is primarily for the Order whose monastery it is attached to, and the abbey (if the monastery is Benedictine) is headed by its abbot, or its prior if it is only a priory. St. Lazare at Autun is a long generation later than the design of Cluny III; its nave-wall arcade is distinctly pointed, not slightly, and so is its nave vault. Here we see clearly the difference between windows (in the clerestory, with sunlight streaming in) and the triforium just below it, which is blind. The important thing is to understand what a quantum leap has taken place in the grammar and syntax of the nave wall. Now it has the same level of design logic as the Greek Doric had in the age of the Parthenon. At the floor level, we have the compound pier; in the nave arcade, each pilaster in this compound pier terminates in a figured capital from which the arch springs. The pilasters that go up the wall to frame the clerestory windows are punctuated by capital-like mouldings where they cross the string courses above and below the triforium. The reinforcing transverse arches in the main vault visually spring from the center pilaster of the compound pier, which runs all the way up the nave wall to meet it and give it a visual raison d'être. The word "articulation" gets overused, but here it is precisely correct for the logical connectedness of the whole design, in which each part in its function and relationship is clearly related to those to which it is subordinate and to the whole.

The Last Judgment tympanum by Giselbertus is Autun Cathedral's other claim to fame. It was finished by about A.D. 1130. The portal of an early-12th-century Burgundian church is now recessed in the doorway with colonnettes on the jambs. The tympanum (the Latin spelling of the Greek word for "drum") is stone slabs filling the arch over the door, made to be carved and painted--for these tympana were brightly colored, and some even retain part of the color. Vivid subjects were popular, not least the Last Judgment. Before we assume that the church aimed to terrify simple sinners by the images of souls being weighed in the balance and found wanting, then fed to a people-eating device at right (which looks borrowed from an ancient lion's head water spout!), then tormented, in the lower register, we should think how much we "sophisticates" like horror films (not to say more) and how few vicarious thrills were available, by comparison, for medieval entertainment. It is hard to doubt, considering what gets best ratings on television, that the people of Autun dwelt with delicious shivers on the demons, and on the punishments meted out to other people; like the editors of modern art-history textbooks, they probably found the blessed souls on Christ's right hand far less absorbing. In fact, the blessed souls have faces as blissful as kittens being licked by their mother, quite delightful. And in the center of it all is Christ enthroned in an almond-shaped glory (a mandorla), centered and stable and manifestly just, however strict. Giselbertus signed his work, in Latin; he is the first French medieval sculptor to do so, and well he might, for it is a masterpiece. This is the kind of art that is not to be judged by its naturalism but by its overwhelming and unforgettable imaginative power and by the powerful organization of images that holds it all together without reducing it to tiresome rows of dolls.

The energy that drove this new Romanesque is

sometimes connected to the fact that the world had NOT come to an end in A.D.

1000, the Millennium, but we should consider also that population and

prosperity had been increasing steadily, since no new barbarians had come for

more than a century; thus travel, even sailing, became safer, and trade could

develop. It was in this period

that the great pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela became important, and, no

matter how devout pilgrimages are, from the point of view of merchants along

the Route, they are Business.

PILGRIMAGE-TYPE

CHURCH DESIGN

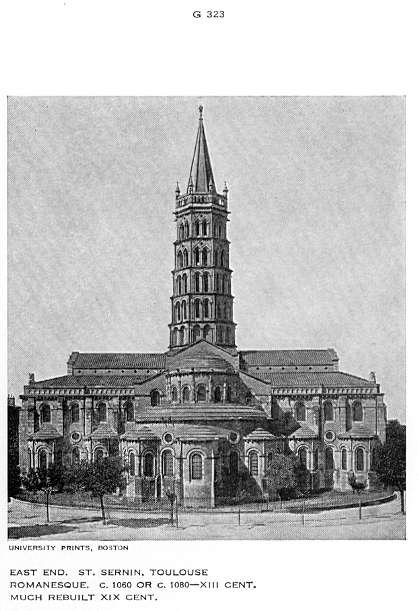

[MG 196] [G 461] Santiago de Compostela in NW Spain (see MAP 18), as comparison of the plan with MG 186 will show, is the same kind of Romanesque church as St. Sernin at Toulouse; there are others of the same type along the Pilgrimage Routes. All have an aisle continuously up one side, around the transept, around the choir and apse (coinciding with the ambulatory there), and back on the other side: you can walk all the way around without ever entering the tall, principal spaces, i.e., the nave and the central nave-like spaces of the transept. The plan is designed for pilgrim traffic. Also defining for the Pilgrimage type are chapels radiating from the ambulatory of the apse (shared with Cluny: it is not one feature alone that defines a type) and a full gallery (second storey above the aisles, opening onto the nave, which we first saw at St. Demetrius in Thessaloniki and in San Vitale, though there in a central-plan church) above the aisles. As the X's on the plans indicate, the aisles are groin-vaulted, and the double lines separating the bays of the tall space (nave and transept) indicate transverse arches strengthening a barrel vault, a round arched barrel vault in these. Pilgrimage churches are rather dark, and a glance at the photo or the elevations tells you why: no direct illumination of the central space; they didn't dare using clerestory openings, as the continuous barrel was very heavy and these large churches have quite high vaults. What is beautiful is the integrity of the fine, solid masonry and the design of the nave wall with its stacked arcades; notice how each arch, large or small, springs from its own capital on its own applied colonnette, just as in the Cluny-type churches of Burgundy, and those that must reach the transverse arches of the main barrel vault are very long, but every arch has its own "footprint" on the floor (so you can read them off the plan!). That compound "footprint" of colonnettes attached to a core pier indicates what we call a compound pier. Now, this logic of columns, capitals, and arches is just a new and wonderful development of the ancient basic idea of superimposed orders.

[MG 196] [G 461] Santiago de Compostela in NW Spain (see MAP 18), as comparison of the plan with MG 186 will show, is the same kind of Romanesque church as St. Sernin at Toulouse; there are others of the same type along the Pilgrimage Routes. All have an aisle continuously up one side, around the transept, around the choir and apse (coinciding with the ambulatory there), and back on the other side: you can walk all the way around without ever entering the tall, principal spaces, i.e., the nave and the central nave-like spaces of the transept. The plan is designed for pilgrim traffic. Also defining for the Pilgrimage type are chapels radiating from the ambulatory of the apse (shared with Cluny: it is not one feature alone that defines a type) and a full gallery (second storey above the aisles, opening onto the nave, which we first saw at St. Demetrius in Thessaloniki and in San Vitale, though there in a central-plan church) above the aisles. As the X's on the plans indicate, the aisles are groin-vaulted, and the double lines separating the bays of the tall space (nave and transept) indicate transverse arches strengthening a barrel vault, a round arched barrel vault in these. Pilgrimage churches are rather dark, and a glance at the photo or the elevations tells you why: no direct illumination of the central space; they didn't dare using clerestory openings, as the continuous barrel was very heavy and these large churches have quite high vaults. What is beautiful is the integrity of the fine, solid masonry and the design of the nave wall with its stacked arcades; notice how each arch, large or small, springs from its own capital on its own applied colonnette, just as in the Cluny-type churches of Burgundy, and those that must reach the transverse arches of the main barrel vault are very long, but every arch has its own "footprint" on the floor (so you can read them off the plan!). That compound "footprint" of colonnettes attached to a core pier indicates what we call a compound pier. Now, this logic of columns, capitals, and arches is just a new and wonderful development of the ancient basic idea of superimposed orders.

[K 50] The Church of La Madeleine at Vézelay has perhaps the most well known tympanum sculpture; with Christ in the

center as at Autun, its subject matter is rarer than a Last Judgment; it is the

Mission of the Apostles at Pentecost

(Acts 2). Because the apostles are to go out and spread the gospel to

all lands, in the compartments around the main picture are very odd

representations of foreigners, such as were mentioned in third- or fourth-hand

accounts in manuscript books describing far-off places that no one had visited

in person: two men with pigs' snouts for noses derive from some traveler's

having said that in Ethiopia men are pig-nosed! When transportation and communications are terribly limited

it is understandable that people might be fascinated by almost any

"precious" tidbit of information; consider how today many will

believe almost anything about extraterrestrials, which, similarly, they can

know nothing about. In the voussoirs around the tympanum are the

signs of the zodiac, again to signify the universality of the Mission. It is easy to become distracted by the

iconography and forget to look at the art, at the style of the sculpture. It is extraordinary and wonderful,

elongated expressively, gesticulatory and animated. It is utterly different from earlier, sometimes awkward

departures from naturalism. No one

could mistake this for inability to imitate nature; it is a style of art that

has nothing to do with imitation or the empirical study of organic articulation

or any sort of illusionism. What

has happened is that many generations of workshop tradition and familiarity

with late Roman provincial monuments (which also accounts for the use of fluted

pilasters that we saw in Autun Cathedral), after a whole generation of

Romanesque architectural sculpture since the time of the Cluny capitals with

the Tones of Music, etc., in the hands of a very gifted and confident sculptor

with a powerful vision of what he wants to accomplish, has coalesced in an

unforgettable, unified style.

Notice the hems of the drapery, where we see the very apotheosis of that

ancient uplifted bit of drapery that we have been noticing since the end of the

5th century B.C. It is hard to

imagine developing this style much further in the same direction. Indeed, in about 15 years, up around

Paris, we shall have the genesis of a whole new approach, a new beginning.

[K 324] The trumeau

is the center post supporting the main lintel of a church's portal. Those at Moissac and Souillac

both are decorated with crisscrossed, exotically stylized animals. The crisscross decorative arrangement

comes from contemporary manuscripts: an initial I, for example, might be ornamented in this way. But the stylization of the animals also

derives from Middle Eastern metalwork vessels, a certain number of which had

been imported into Europe, and survived, which Europeans metalsmiths had been

inspired by (this inspiration is obvious in some 12th century animal-vessels

made for pouring water on the priest's hands preparatory to the Mass). Romanesque architectural sculpture uses

this style much as Late Roman used vine scrolls, with or without animals and

figures. The Moissac trumeau on

the adjacent side has a cross-legged prophet in an elongated gesticulatory

style of great power, refinement, and expression, comparable to that of the

Christ in the Vézelay tympanum.

HALL CHURCHES

[MG 33] The façade of Notre Dame la Grande de Poitiers is broad and low, approximately square. This is because it fronts a church with aisles nearly as high (given the slope of the roof) as its nave (see the next). Such Romanesque churches are found in southwest France (hall churches, later, are popular in Germany). Its portals are recessed with setbacks and with colonnettes on the jambs. Sculpture is confined to blind arcades on the façade--very Romanish, indeed. It is as different as can be from Cluny III or Autun or a Pilgrimage Church.

[MG 33] The façade of Notre Dame la Grande de Poitiers is broad and low, approximately square. This is because it fronts a church with aisles nearly as high (given the slope of the roof) as its nave (see the next). Such Romanesque churches are found in southwest France (hall churches, later, are popular in Germany). Its portals are recessed with setbacks and with colonnettes on the jambs. Sculpture is confined to blind arcades on the façade--very Romanish, indeed. It is as different as can be from Cluny III or Autun or a Pilgrimage Church.

[1617] One of the most remarkable and

wonderful surviving Romanesque historical and artistic documents is an embroidery. We call it The Bayeux Tapestry, but it is not what we

mean by that word. It is yards and

yards of hand-loomed linen, embroidered in wool, almost entirely in chain

stitch, with which you can fill in areas of solid color as well as make strong

outlines. Its date is certain; it

was made almost immediately (but so much embroidery wasn't done in a day) after

the invasion of England, culminating in the Battle of Hastings in 1066, by

William of Normandy, William the Conqueror. Traditionally it was made "by" (at the behest of)

Queen Matilda. Even without making

allowance for the embroidery medium, or the fact that it was made in Normandy

rather than central France, its approach to composition and its figure style

are quite compatible with the style of the vault of St. Savin sur

Gartempe. Like the Parthenon

frieze or the windings of the Column of Trajan, the Bayeux Tapestry is

endlessly interesting from end to end.

It records in short texts labelling vivid embroidered pictures the whole

history of the campaign: diplomatic missions, the army crossing the English

Channel in boats, and all, not only the Battle

of Hastings itself, but it is a detail from the Battle that you have

in your Print, vividly illustrating the text, HIC CECIDERUNT SIMUL ANGLI ET

FRANCI IN PRELIO = Here fell at one and

the same time English and French in battle. You don't need illusionism to convey the shouts and groans

or the cry of a horse breaking its neck, and we hardly notice that red, green,

yellow, black and white are the only colors.

[K 204] Coming from these (deliberately--to

maximize the contrast between the styles) the Bronze Baptismal Font of St. Barthelémy at Liège by Renier de Huy

is even more remarkable. It is a

little later, but that is not the reason for its classical-looking naturalism,

its suave refinement, its superb mastery of bronze casting and finishing. This work comes from the valley of the

Meuse River (Verdun, of World War I fame, is on the Meuse; the river runs northward,

from France, through Belgium, into Holland), so it is called the Mosan style. Back to

Carolingian times, this region had a strong classical tradition. The artist and/or the prelate who

commissioned the font had in mind one of the Wonders in Solomon's temple, made

by Hiram of Tyre, a Phoenician (I Kings

7: 23-26), hence the 12 oxen, but in Christianity they refer to the 12

Disciples. The way that the waters

of the Jordan rise conically and ensure Jesus' modesty may come from a

Byzantine prototype (cf. [MG 42]).

The soft and natural drapery, responsive to the bodies inside it, the

gentle faces with softly waving hair framing them, and, most of all, the

diagonally draped figure in process of pivoting and turning his head are an

astonishing anticipation of High Gothic figure style a century later, to the

formation of which this Mosan work may have contributed.

NORMAN AND

ANGLO-NORMAN CHURCHES

[MG 45] [G 263] [G 329] At Caen (to Americans, the city nearest

the D-Day beaches) William the Conqueror founded two monastic churches: the Abbaye aux Hommes, St. Etienne, and the

Abbaye aux Dames, Ste. Trinité,

similar and equal but not quite alike, the examples we use to define Norman

Romanesque style. Everything about

them is important. The two-tower

façade is both a development from the early medieval Westwerk (as at St. Pantaleon, Köln) and the starting point for the

Gothic façade (as at Chartres, for example, [G 269]). The upper parts of the towers (as you might intuit just by

looking at them) were finished later than the lower parts. The masonry is of the highest quality,

which, as we shall see, permitted innovations in vaulting. The nave of St. Etienne has the logical

design, with colonnettes provided for each arch, as we have seen elsewhere;

like the Pilgrimage churches, it has a gallery over the aisles, but, like

Cluny, it also has a clerestory.

The architect dared combine them because his new high vaults don't weigh

as much, and they don't deliver their burden and thrust evenly like a barrel

vault, because they are groin vaults with ribs. Let's review a bit to get our ducks in a row: groin vaults

go back at least to Rome; ribs were used, e.g., in the domes of both the

Pantheon and Hagia Sophia, but all of those were in concrete and/or brick. Even as St. Etienne is rising, so is

Speyer Cathedral (see below) with mortared cut stone (masonry) groin vaults,

but without ribs, and St. Ambrogio in Lombard Milan with brick-ribbed groin

vaults but not in mortared cut stone (masonry) but a brick and mortar mix. The two Caen Abbayes have cut-stone groin vaults with cut-stone ribs, and the

construction method is new: the ribs are built first, and when they are set

wooden movable forms are hung from the ribs, and on these properly curved forms

the masonry vaults, one section, from rib to rib, at a time. Before, one had to construct, from the

floor up, in wood, stout forms on which to lay the vaults, one whole bay at a time; it took more wood, more

time, more labor. Now only the

forms (centering) for the slender

ribs have to be erected all the way from the floor. What is more, since the curvatures to the lines of the ribs

channels the weight/thrust almost entirely into the piers, and the rest of the

vault can be thinner, so lighter, the wall has less work. So we come back to the clerestory; this

is why the architect dared a clerestory above a gallery and why the nave is

better lit. This is a major

breakthrough, very elegant engineering, and all done by practice, tectonic

vision, and rule of thumb. This

kind of vaulting will be one of the ingredients that go into the birth of

Gothic engineering. St. Etienne

has square bays; the intermediate lighter piers correspond to a transverse rib

(not heavier than the other ribs), on which the diagonal ribs intersect, making

in the vault a square bay divided into six sections: a sexpartite rib vault.

The diagonal ribs are depressed (less than a semicircle) so as not to

rise too much higher than the transverse rib. Now let's look at the nunnery church, Ste. Trinité. It also has ribbed vaults, but its

cross-section is different from St. Etienne's; it has tallish aisles without a

gallery, but a blind triforium such as we saw in Cluny III. The cross-section is very useful; it

shows how a triforium corresponds on the interior to the sloping aisle roof

outside; one more thing: hidden under that aisle roof is a half-arch

buttress. This is the kind

of arch buttress that, moved outside and grounded in a tower buttress, will

become a flying buttress in Gothic architecture.

RHINELAND

CHURCHES

[G 492] [G 500] Even the beginner in reading architectural style can see that these two churches belong to the

same building tradition and that tradition rooted in Ottonian building as in

St. Pantaleon, Köln, and St. Michael's Hildesheim. Maria Laach is an abbey church, good sized,

but Worms Cathedral is a great city cathedral. But both have two transepts with round towers attached, and

both have crossing towers over the intersections of both transepts and the

nave. Both have the exterior walls

articulated with the rows of arches and lesenas

(the vertical flat strips), which come from the brick work of Lombardy (cf. the

taller tower of St. Ambrogio, Milan, in [G 165]) and which we already noted on

the Westwerk of St. Pantaleon. Speyer Cathedral, mentioned above, the

Imperial church of the Holy Roman Empire, is of the same type and even grander

than Worms. Although these

Rhineland churches in the nave still have solid walls, with neither triforium

nor gallery, they have colonnettes running from the floor to each arch,

including one all the way to the transverse arch dividing bay from bay, making

compound piers and articulating the nave wall, and they are vaulted, with fine,

solid stone vaults, plain groin vaults without ribs here. The basic design is very traditional,

but the vaulting is excellent, and at Speyer the vaults are 107' from the

floor, higher than the pointed barrel vault of Cluny III; only the great Gothic

cathedral vaults will be higher.

ITALY: LOMBARDY

[G 165] [G 166] [MG 174] St. Ambrogio in Milan (there has been a church here almost since the time of St. Ambrose himself; he died in A.D. 397) also is true to its old regional tradition. It is built in brick. It has an atrium, and its façade has a tribune from which a crowd in the atrium could be addressed, just as Old St. Peter's had. Its bell towers stand close to it but are built separate from it, as at Sant' Apollinare in Classe (not to mention Giotto's tower at Florence Cathedral and the leaning tower at Pisa Cathedral). The small, plain tower is older than the Romanesque church. The octagon for the unique tower over the last bay before the choir, which was an excellent afterthought, is formed with squinches from arch to arch of the crossing square. True to Italian tradition, the interior is broad and low, compared with Romanesque churches north of the Alps. But, it has compound piers, and a gallery over the aisles, and it is groin vaulted . . . with ribs, but ribs built like Roman ribs, and the vaults are very heavy, so in the nave there is no clerestory (the brilliant idea of the octagon tower with windows compensates). The diagonal ribs are complete semi-circles; since a2 + b2 = c2, it follows that the groin vaults are domed, and, as you see in the photo and in [MG 174], the feeling is almost as if you actually had domes over each bay, separated by the lower transverse arches. As you plainly see, just because two churches both "have groin vaults" does not mean that they are alike

[G 165] [G 166] [MG 174] St. Ambrogio in Milan (there has been a church here almost since the time of St. Ambrose himself; he died in A.D. 397) also is true to its old regional tradition. It is built in brick. It has an atrium, and its façade has a tribune from which a crowd in the atrium could be addressed, just as Old St. Peter's had. Its bell towers stand close to it but are built separate from it, as at Sant' Apollinare in Classe (not to mention Giotto's tower at Florence Cathedral and the leaning tower at Pisa Cathedral). The small, plain tower is older than the Romanesque church. The octagon for the unique tower over the last bay before the choir, which was an excellent afterthought, is formed with squinches from arch to arch of the crossing square. True to Italian tradition, the interior is broad and low, compared with Romanesque churches north of the Alps. But, it has compound piers, and a gallery over the aisles, and it is groin vaulted . . . with ribs, but ribs built like Roman ribs, and the vaults are very heavy, so in the nave there is no clerestory (the brilliant idea of the octagon tower with windows compensates). The diagonal ribs are complete semi-circles; since a2 + b2 = c2, it follows that the groin vaults are domed, and, as you see in the photo and in [MG 174], the feeling is almost as if you actually had domes over each bay, separated by the lower transverse arches. As you plainly see, just because two churches both "have groin vaults" does not mean that they are alike

ITALY: TUSCANY

[B 428] Also, just because churches are in the same modern nation does not imply that they are alike. Tuscan Romanesque is very special. The Baptistery of Florence is much older than the Cathedral it stands in front of. In fact, dating from the middle of the 11th century, it is a little older than most French Romanesque churches. Central-planned, of course; baptisteries are. It is a perfect octagon with an octagonal pointed dome (there are beautiful mosaics on the interior of the dome, which date from the end of the 13th century and are Tuscan Byzantine in style) and a lantern at the top. The sculptures over the three portals, the pedimented window frames, and, of course, their famous bronze doors (in ART 1441) are later. We look at this building a little puzzled. Somehow it looks "Roman", but there is nothing like it in Roman architecture. Roman architecture never had marble veneer on the outside of the building, nor is the marble veneer on the inside of the Pantheon, for example, flat and linear, as this is. What is truly Roman about it is the veritably classical feeling for superimposed and stacked orders, in two clearly defined storeys, and the proportions of the blind arcades, and the true entablature between the arcades and the genuine attic, almost as if the architect had gotten an idea from something in Rome, such as the Arch of Titus. So, since "Romanesque" means "Romanish", this in its own way, is more so than the northern buildings.

[B 428] Also, just because churches are in the same modern nation does not imply that they are alike. Tuscan Romanesque is very special. The Baptistery of Florence is much older than the Cathedral it stands in front of. In fact, dating from the middle of the 11th century, it is a little older than most French Romanesque churches. Central-planned, of course; baptisteries are. It is a perfect octagon with an octagonal pointed dome (there are beautiful mosaics on the interior of the dome, which date from the end of the 13th century and are Tuscan Byzantine in style) and a lantern at the top. The sculptures over the three portals, the pedimented window frames, and, of course, their famous bronze doors (in ART 1441) are later. We look at this building a little puzzled. Somehow it looks "Roman", but there is nothing like it in Roman architecture. Roman architecture never had marble veneer on the outside of the building, nor is the marble veneer on the inside of the Pantheon, for example, flat and linear, as this is. What is truly Roman about it is the veritably classical feeling for superimposed and stacked orders, in two clearly defined storeys, and the proportions of the blind arcades, and the true entablature between the arcades and the genuine attic, almost as if the architect had gotten an idea from something in Rome, such as the Arch of Titus. So, since "Romanesque" means "Romanish", this in its own way, is more so than the northern buildings.

[G 184] [G 185] The greatest Tuscan church that is really Romanesque, although its façade and some other exterior finishing, as well as its wedding cake Baptistery and, of course, the Leaning Tower, are Tuscan Gothic of a special kind, is Pisa Cathedral. Basically basilica-shaped, with a flat coffered ceiling, but with aisles and galleries in its transept as well as its nave (which you can read from the windows and roof levels on the exterior), with uninterrupted Roman columns (real ones, taken from an ancient building)--it still doesn't feel "Roman" exactly. It's the zebra striping (from Islamic architecture, you will recall) and the pointed arch at the crossing, and the crossing tower set on an octagon formed with squinches that give this Tuscan Romanesque interior its exotic flavor. Also, it has rather tall proportions. All these traits taken together give it its unique character.

Breathtaking in scope and so well written!

ReplyDelete