"Barbarians"

is believed to come from the Greeks hearing the speech of their non-urban

neighbors as mere "bar-bar" prattle; it was the peoples on the

northern and eastern fringes of the Hellenistic world who were called barbaroi. How early Germanic language tribes were in central Europe is

uncertain; in his account of the Gallic Wars, Julius Caesar speaks of Germani, but that word is actually a

Latin adjective implying blood relationship (the Spanish word for

"brother", hermano, comes

from it), and the tribes on the upper Rhine thus designated in Latin may have

spoken a Celtic rather than Germanic tongue. In any case, the Hellenized world, both Greek and Latin,

thought of Celts, Germans, Thracians, Sarmatians, Parthians, to name a few, as

radically different from themselves.

When we look at their art, even when it shows the influence of contact

with the Hellenized world, we understand why. In every case, it is an art based on pattern and luxury material

rather than on formal theory and humanistic narrative; that is to say, the

Gauls themselves never even thought of making a "Dying Gaul" or any

other subject based on the heights and depths implicit in being an individual

human being. That is not to

say that the non-urban peoples lacked fine feelings and not to suggest

that they were incapable of making intellectual and humanistically personal

art; after all, given a few centuries, these same populations' descendants

produced all of European art and, in the East, the great mosques of Isfahan and

Samarkand, not to mention Persian miniatures and the Arabian Nights at the court of Harun al Rashid (786-809). Study of the world's arts shows that homo sapiens everywhere can, and will,

in the space of a few generations, learn to produce whatever art forms he

conceives to be desirable. What

their art tells us is that at the time of the Late Roman Empire they had not

desired to make art at all like that of the Hellenized ancient world's

art. At this time, too, the

"barbarians" are becoming part of the urbanized (civilized) world,

and we shall see the fascinating process of new art being born in mixed

cultures.

In Late

Antiquity, we see Greco-Roman traditions deeply modified in Coptic Egyptian and

Sassanian Persian art, but also in great, prosperous cities the curious

transformation of pure Greco-Roman art, long before the Early Byzantine

(Justinianian) period, into a cooler, drier, more "academic" style,

of which fourth-century gilt-glass portraits and ivory diptychs offer excellent

examples. In some of these, it is

clear that the artists are losing their intellectual grasp of organic structure

(there are related developments at the same time in language and literature). The fourth and fifth centuries after Christ

are pivotal. It is these centuries

that are called "Early Christian" in those countries where the church

was already established with authority.

"Early Christian" is not a style; the styles of Late Antiquity

are shared in the Greco-Roman world of these two centuries with the art of

other religions (until these are put down by Theodosius, emperor 379-395) and

with secular art; furthermore, there is already a clear difference between the

art of the Greek-speaking world, descending from the art of Greece and Asia

Minor from Alexander down to Constantine and less affected by barbarian

migrations, and the art of the Latin-speaking world. The former will become Byzantine art, the latter western

Medieval art.

These

differences extend even to the shape of the principal building type, the Early

Christian basilica, depending on whether the particular building is built to

serve the Greek or Latin rite. Old

St. Peter's, St. Paul's Outside the Walls, and Sta. Maria Maggiore, all in

Rome, exemplify the type of the Latin rite.

Capital of

Roman Empire moved to Constantinople

330

Julian the Apostate, last Pagan emperor, 361-363

Theodosius I, the Great, 379-395

his sons: Arcadius (east), Honorius (west)

End of western Roman empire, 476 (to Odoacer the Goth)

ALSO:

Sack of Rome by Visigoths, 410

St. Augustine, died 430

St. Ambrose, died 397

St. Patrick, died (?)461

St. Benedict, died 543

Theodoric the Ostrogoth (Dietrich, in German), died 526

Julian the Apostate, last Pagan emperor, 361-363

Theodosius I, the Great, 379-395

his sons: Arcadius (east), Honorius (west)

End of western Roman empire, 476 (to Odoacer the Goth)

ALSO:

Sack of Rome by Visigoths, 410

St. Augustine, died 430

St. Ambrose, died 397

St. Patrick, died (?)461

St. Benedict, died 543

Theodoric the Ostrogoth (Dietrich, in German), died 526

Some

of the pieces that will be considered in this section of the course are earlier

than Constantine, some later; some are secular art, some sacred, and of the

latter not all are Christian, because other religions persisted among persons

who patronized arts and some of the peoples north of the Alps had not yet heard

of the Mediterranean religions.

But all of the art of late antiquity, in one way or another, shows the

traditions that had been inherited from the Hellenistic world slipping into

oblivion and/or falling under the impact of outsiders' art. In this course, we can only touch on

this complex and difficult period, but we cannot ignore it without rendering

the art of succeeding centuries unintelligible.

[K 305] By the 4th century A.D. there were eastern

(Ostro-) and western (Visi-) Goths all over Europe, and the Celtic peoples

(Caesar's Gauls and their cousins) were hard pressed. Behind the Goths were the central Asian Huns (who, with the

Magyars, gave their name to Hungary).

The European regions that were most deeply Romanized are those that

speak Romance languages today. The

artistic traditions of the Goths and even the Celts, who had known Greeks,

Etruscans, and Romans for so long, were radically different from the traditions

of Mediterranean and Near Eastern civilizations, in one way more like the

Scythians, because these peoples had not been urban before they came into the

urban Greco-Roman world (for they came into Asia Minor, too, and a German

tribe, the Heruli, had invaded Athens, Greece, in the 3rd century), and most of

their surviving art is jewelry, weapon adornments, and horse trappings. Consider the Brooch from Szilágy Somlyó

in the Hungarian-speaking part of Rumania and the Fibula in the form of an Eagle. The east European brooch has no figural representation at

all; what matters to these people is the beauty of the colored gems and the

precious metal setting, the craftsmanship that does honor to the lucky owner,

and the design as such. Although

the eagle fibula (a fibula is a safety-pin)

is representational, the eagle is maximally abstracted, and the value of the

metal, the colors of the gems, and the design as such are what really

matter. Both of these pins are for

fastening cloaks and are executed in cloisonné,

of the kind called champlevé, in

which the dividers that define the cells in which the gems (cut to shape) are

placed are not soldered onto a flat piece but are left standing and are part of

the backing. Almost all of the

Gaulish and Gothic (German) tribes knew this technique, the latter probably

having learned it from the former.

We shall also see cloisonné done with enamel.

[M 188] Much earlier are the Celtic finds from

England that were being made just about the time that Julius Caesar invaded

England and through the Julio-Claudian dynasty. These represent the last Celtic art from England that is not

stylistically mixed with the art of the ruling Romans (called Romano-Celtic)

and, after the 5th century, with the art of Germanic Angles and Saxons and that

of Mediterranean missionary monks.

Archaeologists call the Celtic styles of Europe that follow the

Hallstatt (the Vix Krater was in the tomb of a Hallstatt Celtic princess or

priestess) "La Tène". This art is technically superb and elegantly curvilinear

but, like the Germanic pins, it abhors representing things as we see them. La Tène designs were originally

inspired by the floral patterns on imported Greek and Etruscan pottery and

metalwork, but the Celtic artists relentlessly abstract from them the

pure curves and recurves in never-ending movement that are the essence of their

art. Thus the Celtic art, although

fundamentally different from Germanic art, is just as radically unnaturalistic,

just as devoted to colors and materials and craftsmanship. The famous examples that we have here,

the Desborough Mirror and the Battersea

Shield, are both on view in the

British Museum.

[K 173] The gilt glass portraits (most are portrait miniatures) of the

3rd and 4th centuries, however, come from the very heart of the Greco-Roman

world and were made for members of the upper classes. Whenever the persons are named, the writing is in Greek, but

we don't know exactly where in the wide Greek-speaking world they were made. The flecks of gold leaf and black paint

(sometimes with other colors) are applied on the back of the glass,

which is mounted in metal, so that the easily damaged image is protected. Thus, they remind us of miniatures in

lockets or of silver-on-copper daguerréotypes, which had to be covered with

glass and framed similarly. Like

the ivory diptychs (they are contemporary with the earlier ones), the gilt

glass portraits show us the faces of the leisured and cultured classes of Late

Antiquity holding onto their values and the remnants of a lifestyle for dear

life, as we feel, also, reading Boethius's Consolation

of Philosophy or the poetry of Ausonius or the anonymous masterpiece, Pervigilium Veneris. The Bouneri and Kerami medallion is exactly

at the watershed between "Late Roman" and "Byzantine"

style. It shows how much of the

understanding of drapery folds (even in the heavy brocaded fabrics now worn by

those who can afford them) and of the structure of the face (the shadows that

create the relief of the noses represented frontally are perfectly understood

and rendered), for example, will survive intact in Byzantine art, while the

feeling of the portrait images, with their frontality and intense, staring

non-expressions, is distinctly post-Constantinian. There is no way of telling what religion these people

believed; the style is pervasive in their socio-economic class.

[K 223] Weaving is something else:

multi-colored flat weaves, such as twills, with silk or wool weft on a cotton

or linen warp, necessarily simplify and schematize flowers and figures. Prized patterned textiles were made and

exported in Late Antiquity not only from Sasanian Persia (the most beautiful,

silks, which made their way west, as well as east to China via the Silk Routes and were widely imitated) but from Egypt

("Coptic" because the town, Coptos, near Luxor was a trading center

of the Christian Egyptians in the pre-Islamic centuries). Coptic

Textiles have a wide variety of

motifs, mostly from ancient mythology but some Christian, in a style more

remote from the ideals of classical tradition than the weaving technique as

such demands.

[O 416] The Sasanian Persians (whose religion

was Zoroastrian) ruled a great empire, bridging from the Greco-Roman world to

the Indo-Chinese world (226 until the Arab Conquest in 640, whereupon the last

Sasanian king fled east and died a refugee in China at the Tang court). Pervasive western ignorance of the

history of the pre-Islamic Iranian middle east is abysmal and as much

responsible as anything else for our diplomatic difficulties in this part of

the world. Ardashir I took

Ctesiphon, their capital, from the Parthians (remember the recovery of the

Standards from the Parthians on the breastplate of the Primaporta Augustus) in

A.D. 226. Shapur I (242-272) built

the magnificent new palace at Ctesiphon,

with its imposing hairpin-shaped brick vaults over the audience hall. Here we see the Sasanian architect

handling superimposed orders in his own way, using "blind" arcades in

a manner appropriate to brick. We

saw long ago that the absence of stone quarries in southern Iraq and Iran made

the successive peoples who inherited the traditions going back all the way to

the Protoliterate Sumerians the world's innovators in construction and design

in brick. Early Byzantine

builders, as in Hagia Sophia, learned not only from Roman but also from Persian

brick, while Islamic architecture in brick, after the Arab conquests, is, of

course, the direct descendant of this tradition.

[O 418] Near Persepolis, where earlier we

studied the Achaemenid palace begun by Darius the Great in 521 B.C., are the

cliffs at Naqsh-i-Rustam, in which

the tombs of the Achaemenid kings, including Darius, are cut out of the living

rock. Below the ancient tombs, on

the face of the cliff, are the reliefs

of Sasanian kings, the same sort of thing, you could say, as the reliefs on

the Arch of Titus 180 years earlier, but from the other side's point of

view. It is because of this

relief, showing the triumph of Shapur I

in A.D. 260, that, when we studied the portrait of Gallienus, I mentioned that

he was the son of Valerian; Valerian is the Roman emperor shown kneeling before

the magnificently mounted Shapur I.

These also are the enemies from whom the Romans learned of the slatted

armor we saw on the Porphyry Tetrarchs and the use of large army horses capable

of carrying the extra weight of horse armor. Learned the hard way: in 260 A.D. Valerian's army was

destroyed by Shapur's, and there were barbarians in Greece (Heruli), Asia

Minor, and northern Italy (note that I do not call the urban, literate

Sasanians "barbarians"), which his son Gallienus could not hope to

cope with. On the other hand, the

Naqsh-i-Rustam relief is eloquent witness to the long, continuous contacts

between the Persian and the Greco-Roman world: Valerian kneels in 3/4 view,

with pleated drapery--but wears Persian trousers; both Shapur and Valerian,

although not in motion, have flying capes (that go back to examples such as the

Stele of Dexileos of 394 B.C.) but with very oddly stylized folds. Once again, it is a case of artists' using

something not created and developed in their own tradition, but here they make

something out of it more original than at Palmyra.

[O 424] The Sasanians are most famous for the

patterned silks from the royal looms

and for their metalwork, both of which

were exported and prized far and wide, influencing these mediums in both

Byzantine art and Chinese art, affecting even early medieval metalwork in

western Europe. Our example, the Silver Plate of Khusraw II Hunting, is

late Sasanian, so contemporary with the Early Byzantine empire rather than the

western Romans; in fact, Justinian's general, the great Belisarius, had to

fight his father Khusraw I; this time Belisarius was the victor, and we see a

Renaissance idea of the battle by Piero della Francesca in the True Cross Cycle

of frescoes at Arezzo (Khusraw, Khosru, and Chosroes are variant spellings of

the same name, the last being what the Greek sources call him). From the point of view of 15th century

Italy, Chosroes is just one more "infidel" for the Cross to

conquer. As comparison with the

Silver Missorium of Theodosius I, [K 216], below, suggests (and many other

examples could be compared), between the 3rd and 6th centuries there was a

great deal of artistic cross-fertilization between middle eastern and

Mediterranean metalworkers. Note

that the iconography is the Royal Hunt, with exactly the same meaning as in the

Assyrian lion hunts at Nimrud and Nineveh.

Now we turn to the Christian art

of the Late Antique Greco-Roman world, from Constantine to Justinian. This is imperial Christian art, no

longer the art of one of the minority religions, but it antedates the end of

the Empire in the west, and it also antedates the Age of Justinian, when the

term Early Byzantine becomes truly appropriate for the Christian art of the

Greek-speaking world.

[MG 52] [MG 53] [MG 54] The Old Basilica Church of St. Peter is not significantly later than the completion of the Basilica Nova, though it dates from the second half of Constantine's reign. In its structure and its basic design, unlike the Basilica Nova, it is a typical traditional basilica with a flat timber roof and regular colonnades separating the nave (central space) from the aisles and a regular clerestory wall, as we saw at Pompeii and in the Basilica Julia in the Forum Romanum (also Trajan's Basilica Ulpia), rising above the aisles for high windows to light the nave. On the other hand, it is a religious building, so it has the orientation of a temple, with the entrance aligned with the apse at the opposite end. Most Roman temples after Augustus had apses. In the Roman temple, the statue stood in the apse; in the Christian church, the altar (often raised on steps, a bema) stood in front of the apse, which framed it. The Roman temple was placed at the end of a colonnaded forum (as we saw already at Pompeii); the Christian basilica has a colonnaded courtyard in front of it, which now assumes the name atrium that three centuries earlier had named a room in a Roman house. Constantine's architect used the basilica form for a church, because Christianity is a congregational religion, whereas people used Roman and Greek temples singly or casually, a few at a time; a basilica is par excellence the building type capable of holding many people, and, because in the early centuries of the church, only the baptized could be present at the Holy Communion, Christians could not hold their rites in the open, as the ancient Greeks had done (except in the Eleusinian Mysteries). The catechumens (those being instructed, not yet baptized) could congregate in the atrium. Old St. Peter's has one feature that will be widely influential in the future, a feature that other Early Christian basilicas do not have, so when we see it later we know where it comes from: the transept. As the Latin name implies, it cuts across between the nave and the apse, and it is high-roofed like the nave, and thus is just as apparent on the exterior as when you are inside. It makes the plan T-shaped. At this date the cross of the crucifixion is a T (tau), and it is hard to doubt that the transept, the one radical innovation here at the invention of the Christian church plan, was devised to make the church building like the cross in which it is grounded. St. Peter's tomb (traditionally, and archaeology suggests probably in fact) was below where the bema of his basilica was sited, and tradition holds that Peter himself was crucified. Old St. Peter's stood until the present "basilica" by Bramante, Michelangelo, and others, was built in the 16th and 17th centuries. Our knowledge of the old basilica is based on excavation and on numerous drawings of it made shortly before it was torn down. These show the timber roof open, without a coffered ceiling.

[K 3] The Standing Good Shepherd in the Vatican Museum, as well as the Seated Young Christ, Teaching in the

Vatican, also continue Roman style of the late 3rd and early 4th centuries,

only with Christian subject matter.

Until the 6th century, in the West, Christ is regularly young and

beardless, often resembling a young Orpheus or a young Apollo (whose images had

been among the prototypes for those of the new state religion). As in the Lot and Abraham mosaic, the

figures are somewhat short and large headed, but also beautiful and, although

the running drill is much in evidence, it is used adroitly and does not look

like just so many random slots.

The most important point is that the overall feeling of these images is

idealized but not august, not severe, not royal.

[K 144] The perfect example of the style we

have just seen in the round is the Sarcophagus

of Junius Bassus, who was the urban prefect of Rome (≈ mayor) and died in

A.D. 359, so this is the dated sarcophagus of a well documented person. The Seated Young Christ, in particular,

closely resembles the Christ enthroned in the center of the upper register on

the Sarcophagus, which was found in the grottoes under St. Peter's. Now, why is the University Print

labelled "Greco-Roman-Asiatic"?

The sarcophagus is of the type, with niches formed by little

columns, that since the 2nd century was usually made in western Asia Minor

(other types were made in Athens and Italy). Besides, the almost lacy architectural details, done with

the drill, are usually seen, full size, in Greece and Asia Minor (for example,

in the architectural members of the real palace of the emperor Galerius

excavated in Thessaloniki in northern Greece). Once again, therefore, the stereotype of "typically

Roman", "purely Western" is challenged. Moral: humanity has a hard time

outgrowing unscientific separatisms.

Was the sculptor of this Roman prefect's sarcophagus from Asia

Minor? Where, then, was the

sculptor of the Seated Young Christ trained? For that matter, whom did Constantine (who ruled, mostly,

from Constantinople), or his agents, choose to work for him in Rome? We don't know, but 4th and 5th century

art from Italy is, on the whole, different from that of Greek cities.

The Sarcophagus of Junius Bassus gives us a fine repertory of standard compositions for Biblical subjects in the middle of the 4th century: The Sacrifice of Isaac, Christ Arrested, Christ between Peter and Paul, Christ brought before Pilate, Christ washing his disciples' feet, Adam and Eve, Palm Sunday (with Zacchaeus up in the tree), Daniel in the Lions' Den, Christ being led away.

The Sarcophagus of Junius Bassus gives us a fine repertory of standard compositions for Biblical subjects in the middle of the 4th century: The Sacrifice of Isaac, Christ Arrested, Christ between Peter and Paul, Christ brought before Pilate, Christ washing his disciples' feet, Adam and Eve, Palm Sunday (with Zacchaeus up in the tree), Daniel in the Lions' Den, Christ being led away.

[K 221] The ivory panel with the Maries at the Tomb and the Ascension of Christ,

on the other hand, is one of a group of wonderful ivories made around 400 that

are thought to have come from workshops in northern Italy, perhaps in Milan

(ancient Mediolanum). These are

wonderful because, although their subject matter is Christian and the figure

proportions are short-bodied and large-headed, so much of what was vital in

classical art is alive in them.

Instead of imitating something Augustan or Hadrianic, these artists to a

remarkable degree still understand the underlying principles that gave the old

styles their emotional power and sense of rightness. Take the figure of Christ, with the feet firmly set, with

the drapery pulled tight, grasping God the Father's outstretched hand so you

know he won't let go. Take the

mournful figures sobbing and leaning on the tomb. Take the lovely figure of a wingless angel at lower left,

looking like the young philosopher, Christ in the Temple-type,

teaching-gesture Christ, whose speaking gesture tells the Maries that he is not

here but risen. And these figures

are only about three inches high.

Of course, the story and the message are all-important, and the built

tomb (a Roman tomb, such as well-to-do families built; the artist was

unfamiliar with the sort of rock-cut tomb that Jesus was actually buried in) is

very small compared with the human figures, but that sacrifice had

already been made in the historical reliefs on the Column of Trajan.

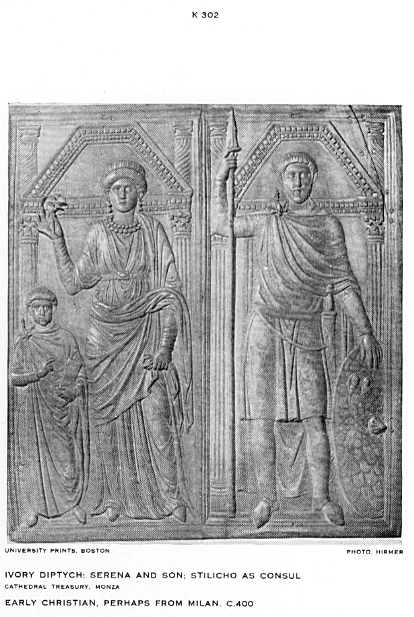

[K 302] The diptych of Stilicho (as Consul) and of his wife Serena and their son

combines the striving for beauty and refined carving of the Symmachi-Nicomachi

diptych and the real understanding of form of the Three Maries/Ascension ivory

with something else: the court style of the emperor Theodosius the Great

(compare the next two works). And

who was Stilicho? He was a Roman

general (Theodosius's chief general, as Belisarius would be Justinian's)

and a great statesman, with Theodosius's niece as his wife, and on Theodosius's

death he was guardian to Honorius, the heir to the throne of the western Empire

(who in 408 had him wrongly killed, Stilicho remaining noble to the end), but

by birth he was a Vandal, a German, whose ancestors a century earlier

had been settled in what is now Rumania.

So much for ethnic labels (from the ravagings in the next century by

Vandal tribesmen we get the word "vandalism"). With the diptych on the occasion of his

consulship before us, we see that he knew and cared, too, about the quality of

artists. The low relief figure of

Stilicho, all in proportion, is perfectly related to the drapery, and the

figure of the little boy is all grace.

Serena, though, is a bit weak in the midsection.

[K 216] The silver Missorium (disk)

with the Emperor Theodosius and his sons Arcadius and Honorius (heirs, respectively, to the

eastern and western halves of the Empire) is of the same date. The emperor in the center is framed by

the arcuated lintel of a temple pediment; in the intercolumniations left and right

are his sons; Arcadius, the elder, is the larger figure at left. Outside the temple-façade that frames

these rulers by divine right (that is the idea, now that Christianity precludes

their being divinized in person) are their armed bodyguard. This is Constantinopolitan imperial

iconography, out of which Byzantine imperial imagery will develop. Like Stilicho's, their figures are tall

and slender, and although attenuated (not solid looking) to the point of

suggesting disincarnation and frontal (because iconic), are perfectly related

to their courtly draperies. The

logic of drapery is preserved.

[K 197] You may remember that one of the

centers from which the emperor Hadrian ordered sculpture for his Villa at

Tivoli was Aphrodisias in Asia Minor,

so will be less surprised to see the most wonderful full-sized portrait statues

of the early 5th century coming from Aphrodisias. The Statue of an

Official suggests what a full-length three-dimensional marble statue of

Stilicho might look like, if we had one.

Even though the man is represented wearing a loose-draped toga over his

sleeved garment, we still have the strongest sense of the bulk, weight,

continuity, and potential for movement of his body inside it, and none of the

lines of folds or edges of falling cloth are used decoratively but are functional. Also, the man is a real, individual

person. These Aphrodisias statues

are the last of their kind for a very long time; we shall next see his like in

the Gothic period statue of St Theodore, [K 76], at Chartres Cathedral, ca.

1220.

[K 215] In Istanbul you can still see the

outlines of the great Hippodrome, now an open green area, with the obelisk that

Theodosius I (emperor 379-395) had brought from Egypt (because there was one in

the Circus Maximus in Rome). The Base of the Obelisk of Theodosius is

the prime example of what we mean by Theodosian style; it is as if the silver

Missorium, or the diptych of Stilicho, were to be translated into stone relief

(the blue-gray marble of western Asia Minor). The workmanship (we can see this even though the surface is

much worn having been exposed all these centuries) is very fine and exact,

especially in comparison with the narrow frieze on the Arch of Constantine, but

we can no longer speak of a "failure" of naturalism or rendering of

space. Here indeed we have art

that eschews those goals; its goals are divine dignity and gracious power

expressed in formal frontality.

Here is a new art born from an old but with its own agenda. It is the very precision and logic of

the carving that emphasizes the avoidance of any illusionism or anecdotal

sentiment.

[MG 168] [MG 170] [1611] Galla Placidia's Mausoleum at Ravenna is the earliest of the imperial monuments that we shall study there (see MAP 3, south of Venice). She was Theodosius's daughter, Honorius's sister; recent reference books put her death ca. 450. Her life history would make an unbelievable epic movie, with her exerting great influence in the last reel when her son Valentinian III was made emperor. Her mausoleum also is central-planned but in the shape of cross with short, equal arms. Beside the powerful forms of San Vitale, built a century later, it looks like nothing in particular (but then, on the outside, the Pantheon in Rome looks like just a big cylinder). Inside! Almost all the colored marble veneer, the inlaid marble floor, even the alabaster window panes (these may be replacements, but early) are preserved. Above, all is glass mosaic. The vaults are dark blue with patterned stars fit to remind you that heaven is for the vision of God, they are so lovely. One of the mosaics at the end of an arm of the cross shows the deacon saint, Lawrence, whose martyrdom was to be roasted alive on a gridiron, which is shown ready; he has a cross over his shoulder to indicate his following Christ even to martyrdom, but only Late Medieval art would think of physically representing the roasting; here it is the meaning, not the feeling, that matters. The mosaic of Christ the Good Shepherd is different both from the emblematic representations that we saw in the catacombs and from later images of this idea. Christ is still shown beardless, and he is in a natural, twisting three-quarter view pose (how different from the reliefs on the base of Theodosius's obelisk!), and the six sheep are not lined up like symbols but disposed as naturally as mosaic will allow in a Mediterranean traditional rocky, sagebrushy landscape, in front of a pale blue, graduated sky (even the Lot and Abraham in Sta. Maria Maggiore in Rome at about the same date, for all their naturalism, have a gold background); these sheep are not only woolly and modelled in light and shade and seem really to be standing and lying down but two of them are even foreshortened. Not that this is like an American landscape of, say, Yosemite in the 19th century. It is conventional landscape, but the convention that it follows is that in which naturalness rather than emblematic formality is used. As with the St. Lawrence, it is the meaning that matters; this style expresses the real humanity of Christ and the real creaturely relationship between him and his "sheep", his flock; it says that caring is part of and within nature. Yet the artist, dressing Christ in gold, with a purple cloak visible over his shoulder and across his lap, with a golden halo, leaves no doubt that this mosaic represents the risen Christ caring for humankind; a golden cross means that the cross of pain has become the cross of glory. I describe this at length, because when a work of art is ancient and the name of the artist is lost we tend to overlook how much meaning there is in stylistic choices. The people for whom this art was made were not so image-saturated and overstimulated as we are.

[K 5] A hint as to where naturalistic

conventions were preserved, and continued, survives in one of the oldest

complete illustrated books that we possess, The Vatican Vergil.

This is a codex (plural, codices), that is, a book with pages

bound between covers, rather than a rotulus, a scroll; both types were still

used. As you recall, Vergil wrote

the Aeneid for Augustus, but he also

wrote Eclogues, which are bucolic

shepherd poems (not about realistic shepherds, but about Arcadian life as a

return to untarnished, uncomplicated simplicity), and Georgics, which are poems on how to run a farm! Thus he did for Latin what Homer,

Theocritos, and Hesiod had done for Greek. It is the Georgics

that this picture illustrates, and it exemplifies perfectly what is meant by

conventional landscape, naturalistic in intent: the illustrator did not look at

real nature to do it; he had learned how to do it in his apprenticeship; but he

had learned how to make a few plants and buildings give the feeling of

nature. Similarly, by this time,

we have reams of Latin poetry that gives the most delicious feeling of nature

written, in many cases, without so much as opening a window. Eventually, of course, it will lose its

roots and dry up (cf. [MD 35], Adam and Eve at Hildesheim, A.D. 1015).

[K 211] Very obviously, the Mosaics around the Dome of the Rotunda of

St. George in Thessaloniki although also of the first half of the fifth

century (now dated ca. 410) are altogether different. We are back in the world of the Silver Missorium of

Theodosius, but now in a religious mosaic rather than courtly metalwork. On the Missorium it is Theodosius and

his sons that are framed by wholly symbolical architecture; here it is the

saints (Onesiphoros and Porphyrios are only two of them) and in the center of

the dome that they surround was the bust of Christ borne aloft by angels (very little

of this survives). The unreal

architectural forms both on the Missorium and here should remind you of the

Antonine Market Gate of Miletus and even of the upper wall in the Ixion Room of

the House of the Vetii at Pompeii: they all derive from the design of

stage buildings in the theaters of the Roman Empire. In these mosaics this illogical, disembodied architecture is

finally given very specific meaning: rendered in gold and on a gold background

(which is infinite light instead of a mundane sky) it is the City of God

(which just in these years Augustine was contrasting to the World in which the

Church Militant operates).

Logically constructed architecture, no matter how rich, could never

convey this idea; it would look merely like the Palace at Constantinople or

Domitian's in Rome or even Galerius's Palace here in Thessaloniki (the Rotunda,

before it became a church and these mosaics were done, was the mausoleum of the

pagan emperor Galerius, one of the Tetrarchs under Diocletian, who built a

palace and a triumphal arch here, and his mausoleum as Diocletian did at Split;

that is why St. George's is round).

The tall, beautiful saints stand before the City of God, each and every

one of them with his arms raised in prayer (like the orantes in the catacombs); they pray in worship and they pray for

the church of believers. You may

notice that they look like priests celebrating Mass; that is because church

vestments go back to court garments of this period. You may find some book that says that gold is used to make

the picture flat. No. Gold is used for glorious light. The tall figures of the saints are the

equivalent in mosaic of the tall official by a sculptor of the school of

Aphrodisias, of nearly the same date.

It is out of this Theodosian and post-Theodosian art of Greece and

western Asia Minor that Early Byzantine art will come.

*******

No comments:

Post a Comment