|

| The dying warrior in the west pediment is still Late Archaic in character and dies like a warrior by the Berlin Painter |

|

| The exploration of the expressively collapsing muscles and suffering of the dying warrior in the east pediment, only perhaps a decade later is Early Classical |

|

| The figure of Herakles as archer likewise breaks the bounds of Archaic style |

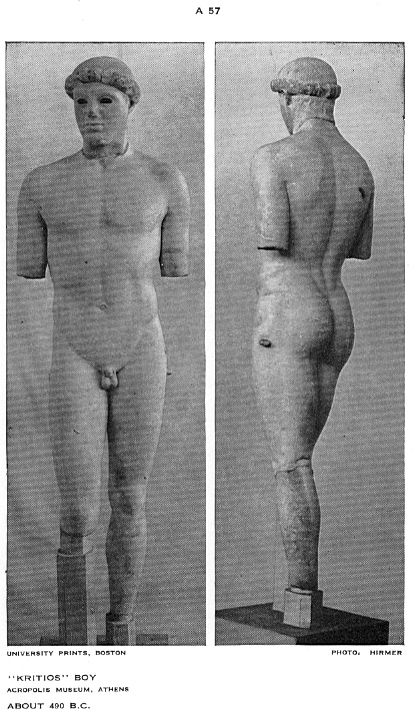

[MA 91] [A 80] [A 79] [A 82] We have just discussed the Temple of Aphaia at Aegina as a Doric

Temple of ca. 500 B.C. Greek

temples were not built in a day or a year; the west pediment sculptures of the Aphaia temple (with Athena standing

straight in the center) seem to date to ca. 490 B.C. and are still Late Archaic

in character; the east pediment, on the other hand, though it represents the

same School of sculpture, participates in the new post-Persian-War approach to

art and is Early Classical in character (some call this the "Severe

Style"). The east pediment (with Athena striding,

her arm outstretched with the aegis over it) is usually dated in the 470's

B.C. The choice of language in the

foregoing sentences is important; this is not linear evolution; Early Classical

is not only a transition from Archaic to Classical but an attitude

distinct from both. B. S. Ridgway

has rightly pointed out that it is more realistic than either Archaic or

Classical; this is the generation when they strive with unmitigated earnestness

to transform the raw data of empirical human vision concentrated on real things

into forms of art. E. R. Gombrich

similarly has called it the shift from conceptual to optical representation: the

Greek revolution. We see the

nature of the change also in the emotional sobriety of Early Classical

art. Compare the Dying Warriors from the corners of the

West and East Pediments at Aegina, some 10 or 15 years apart. Neither has any important deficit in

anatomical knowledge; the real difference is one of approach. The West warrior dies in a ballet pose

that makes a clear silhouette (the Berlin Painter would approve of him) and his

grimace of pain is expressed (perfectly well) in a variant of the "archaic

smile". The East warrior is

based on real study of an expiring body collapsing; the contours of his body

result from this and do not give priority to the clarity of

silhouette. Neither is better than

the other, but they are radically different. Herakles as archer

also is from the East Pediment; he is a younger Herakles than we usually see in

Archaic art, and his face has the new proportions that we already saw in the

"Critian Boy"; the heavy chin with level brow and cheekbones impart

sobriety to the features of the face.

[MA 64] which ornamented the gable of some small

building at Olympia in the

sanctuary, where it was found, is made in the same technique as the Etruscan

striding Apollo from Veii, of hollow terracotta;

indeed some written sources say that the Etruscans learned how to make terracotta

sculpture from a Greek named Euander.

This work exhibits the new natural drapery and facial proportions of

Early Classical art combined with a cheerful buoyancy left over, perhaps, from

Late Archaic. Despite the damage,

notice the ease with which the sculptor renders the boy's body being carried in

the crook of the god's arm; it is Zeus

abducting Ganymedes to take him to Olympos where he will be cupbearer to

the gods, rather like a page at a medieval court.

hand-held and pre-digital but it looks more real

[A 60] [MA 55] Everyone knows about the Olympic Games, which were the

oldest Panhellenic religious-athletic event. But there were Nemean Games, too, and the Pythian Games (of

Apollo Pythios) at Delphi. Pindar,

the great poet whose Odes date from the same decades as Early Classical art,

wrote Odes for the victors in all of them. In this period, Athens was already a democracy, but many

other city states, including those of the colonies in Sicily, still

had tyrannies (like that of Peisistratos in Archaic Athens and of Polykrates in

Archaic Samos). The famous bronze Charioteer of Delphi is part of

an extremely expensive monument set up at Delphi (the foundations of it and

part of the inscription still exist) to commemorate the chariot-race victory of

the team of one of the Sicilian tyrants probably in the Pythian Games of 477

B.C., since the style should not be much later than the mid-470's--in other

words, only a little later than the "Critian Boy" but not Athenian

and of bronze rather than marble, or (compare the faces) about the same time as

"Herakles the Archer" from Aegina. We have, besides the Charioteer, only some horse hooves and

a bit of tail in bronze. There

were four horses led by a young groom, the chariot, and the charioteer standing

in it; though you couldn't really see his feet, they are perfect and

beautiful. Think of the group as

slowly parading past the reviewing stand, the young charioteer standing

straight (like a modern Olympic victor on the stand) but turning his head slightly

towards the judges: contrapposto like

that of the "Critian Boy" thus is precluded. The "lost-wax" hollow-cast

bronze was made in six pieces (the left forearm is missing), with a bronze belt

concealing the waist joint; no statue so large and complex as this can be cast

in one piece, since there is a limit to how far molten bronze will flow before

it cools. When it was new it was

bright as a new penny (but less pinkish), there was silver inlay in the

headband, and the clipped sheet bronze eyelashes were neither corroded nor

crumpled, but the inlaid quartz over brown eyes cannot have looked much

different from what they do today.

If the "Peplos Kore" seems like a perfect Greek girl, the

"Delphi Charioteer" is a perfect Greek boy, beautiful and candid and

noble, kalós k'agathós. Certainly,

the head is the standard for an "Early Classical face"; note, besides

the round large chin and the level cheeks and brow, the very short upper lip;

note how the curls escaping from the headband force forward the shell of the

ear. The drapery is no less

remarkable. Only to the most

cursory and insensitive viewer does it seem uniform; it is characteristic of

Early Classical not to exaggerate for effect. Study how with infinite variety the folds constrained by

cords and belt respond; notice that no two of the long folds obedient to

gravity are the same (if you made a cross-section, it would not look like

regular fluting, just the opposite to Art-Deco drapery) and how the falling

drapery subtly responds to the youth's turning his head and shoulders to his

right. Once again we have an

original masterpiece that is "anonymous" to us, though surely by an

artist who was well known by name in his own time.

[MG 222] [MG 223] The Old Hera Temple at Olympia, which extends, in the photo

of a model in the Olympia Museum, between the round Late Classical Philippeion

and the semi-circular Roman Fountain of Herodes Atticus, is nearly as long

as the Early Classical Temple of Zeus, which was finished by

457 B.C. and is thought to have been built through the 460's, but it is not

nearly so large. In the model, the

Zeus Temple is all white and looks like marble; actually, Elis (Olympia's district)

has no marble quarries, and the temple is built of the local conglomerate,

stuccoed (as Aphaia at Aegina and Corinth were), with only the sculptured parts

and the roof tiles made of marble.

It is by a local architect and has clear and simple proportions; the development

of the Doric Order is by now complete.

The columns were not monolithic and today are represented by rows and

jumbles of fallen column drums.

The restored drawing of the East in [MG 223] shows the rather static

composition of the East Pediment and the akroteria

at the corners and peak of the gable; it also indicates the use of paint (e.g.,

dark triglyphs) and shows the gilded bronze shields that were placed in the metopes. The twelve sculptured metopes with the Labors of Herakles [A 90] were not on the exterior

peristyle (colonnade) but over the

porches: above the columns in antis

of the pronaos and the opisthodomos. The restored cross section of the temple shows its

double-decker interior columnar order, like that at Aegina; it also shows the famous

statue of Zeus Olympios made of gold and ivory (chryselephantine) over an armature, which was included in the list

of the Wonders of the World that started with the Gizeh pyramids. But Pheidias worked from the 440's to

the 420's, so the Zeus statue is not of the Early Classical period. Besides, it no longer exists. It is because of the sculptures of this

temple, in particular, that the nickname "Severe Style" came to be

used of Early Classical art, although it is really the German adjective, "strenge" and not English

"severe" (which has some different connotations) that is meant. Athena, Atlas, and Herakles are

represented as soberly and plainly as they possibly could be; to ease the

burden of the world on his unaccustomed shoulders, Herakles is given a common

pillow, folded double, and Athena herself is dressed in a plain peplos with her hair in a young woman's

everyday coiffure, without a helmet or shield and even without the aegis that is her usual attribute. The artist relies wholly on narrative

clarity of the composition for his story and wholly on human dignity to express

superhuman characters. Only a half

century after the Acropolis kore #674, the sculptor uses no fancy pleats and

diagonal drapes, and Herakles is not made extra burly as he often was in

Archaic art and will be again in Hellenistic and Roman art. He is content, too, with the simplest

composition, with three figures side by side. Here once more Greek art has done something revolutionary,

something that also Early Renaissance artists, like Masaccio, re-accomplished in the 1400's A.D.

|

| This is one of the very oldest of the University Prints! |

MA 66] [A 86] [A 446] [A 89]: The West Pediment of the Temple of Zeus at

Olympia. As comparison of the

two pediments in the reconstructions shows, although the east is the front of

the temple, it is the west pediment that is really exciting and original as a

composition (the individual figures are equally wonderful in both). Its subject is the battle that ensued

when the centaurs crashed the wedding party of Perithoos of Thessaly who was

the best friend of the Athenian hero Theseus, according to the legends. Centaurs were thought to be native to

Thessaly; they were half horse, half human, and their nature, also, was only

half rational; they were particularly impulsive when they had drunk wine. By this period, Greeks used centaurs

and satyrs to express the irrational roots of their own nature. At the opposite pole was the god

Apollo, a very ancient god whose name is not even Greek and may be Anatolian. In Homer and in some old myths (like

that of Niobe, as we shall see) he is a plague god whose arrows kill; by now he

has become a healer and, especially at Delphi, the embodiment of the Greeks'

highest cultural values, such as self-knowledge and self-control. This pediment says it all. The centaurs have come uninvited, drunk

some, lost all control, and are handling the girls, including the bride. The centaurs snort and pant, the Greek

girl expresses distress by only slightly flared nostrils. The young Greeks do their best to

defend their sisters, but the equine and mature centaurs are physically

stronger. Apollo intervenes,

exerting his power by contained strength rather than expended energy; he

outstretches his right arm and the mêlée ceases. To unify the composition, the sculptor carves the scene in

blocks that include more than one figure, and he links all in the general

mêlée; this is a unique experiment that will not recur. He studies real cloth very closely and

does not seem to care whether it looks decorative or not. The head of Apollo is about a decade

later than that of the "Charioteer": the nose is longer, the chin

shorter; the proportions are beginning to change toward the ideal that will

prevail in the next generation.

[A 94] [MA 44] Not all Early Classical art participates in the so-called

Severe Style of Olympia. In the

Museo Nazionale Romano in Rome (until recently housed in the Baths (Terme) of Diocletian, so often called

the Terme Museum) there is a three-sided relief that was found in Rome. Like so much else, it had been taken

there in antiquity, probably from a Greek city in South Italy. It is not earlier than the 460's B.C.,

but probably not later than ca. 450, advanced Early Classical art. It is called the "Ludovisi Throne"; the Ludovisi family once owned it, but

it is not a throne. Also,

it is uncertain whether the main picture is the Birth of Aphrodite from the sea or Ariadne from the earth, nor do

we know the significance of nude girl piping and the veiled female putting

incense in a censer--though theories abound. Make up your own.

If the western Greeks had left us as much literature as the Athenians

did, we'd know better what they thought and meant. The "Ludovisi Throne" is certainly, however, a

masterpiece, in the refined delicacy of the chisel work, in the wonderful

pattern of six arms, in the subtly observed and beautifully foreshortened

figure of the nude girl (one of the earliest real female nudes in Greek art,

and it will be another century before we get a nude female statue). The folded cushions remind one of

Herakles' head cushion on the Olympia metope.

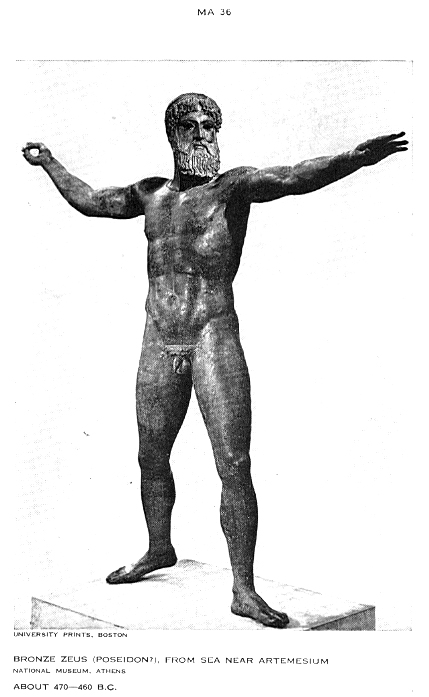

[MA 36] [A 450] Like the "Delphi Charioteer", the God (Zeus or Poseidon) from the sea near

Cape Artemision (the north tip of the island, Euboea, alongside Attica and

Boeotia) is an original bronze masterpiece of the Early Classical period,

obviously by a major master. We

have names recorded of famous sculptors of the generation before

Pheidias and Polykleitos, but we don't have a real idea of their work, so

there's no telling whether the Cape Artemision god is by one of them or by

someone just as good whose name happens to have escaped inclusion in the later

lists. The Cape Artemision god is

not earlier than the west pediment of the Temple of Zeus at Olympia; it already

has the long nose and shaded eyes that point towards the middle of the century,

and the tresses of the hair and beard (only a half century since abandoning

bead patterns for hair!) go much further in suggesting the separateness, and

hairiness, of the tresses than on the "Delphi Charioteer". Here again there is no contrapposto, because, instead, it is

one of those balanced, poised stances on the verge of action that

Classical Greek sculptors loved--the pose of preparing to hurl a javelin, which

could be studied as athletes prepared for the Games, but this is a god: Zeus if

the missile was his thunderbolt, Poseidon if it was his trident; they are

brother gods who otherwise in Classical art look just alike. A god because it is over lifesize and

too mature for an athlete type and wears his hair long, braided and wrapped

around his head, an old-fashioned style (note: it is now that we begin to see

divine figures in art represented in the fashions of the past, as the Virgin

Mary is in Christian art). The

inset eyes as well as their eyelash casings are missing; the groove around the

mouth shows that the lips were copper (pink metal), and so were the

nipples. We owe its preservation

to shipwreck; this masterpiece never got to Rome. Had it reached its destination, we might have descriptions

or marble copies of it and know who did it, but the valuable and splendidly

nude original would surely have been lost. In the perilous years of Late Antiquity or the Early Middle

Ages either Christians or Moslems would have coveted the metal and hated the

nudity. Notice, however, that the

ideal nudity really does seem divinely beautiful rather than humanly sexy; it

is very hard to imagine anyone's finding this statue immoral. The mastery of human anatomy here

approaches sublimity. Even Middle

School children respond appropriately to it, as to Myron's

"Diskobolos".

Note: This statue has a whole blog-Post-essay of his own in TeeGee Opera Nobilia

[A 64]

The Print gives you a modern bronze cast combining the best parts

of two of the best surviving marble copies of Myron's famous Discus Thrower, the Diskobolos,

with his discus complete. More

than thirty full-size copies survive besides small bronze statuettes. It is time to say something about these

copies that we must rely on when the famous originals are lost. They were made because in the last two

centuries B.C. and the first two centuries A.D. (and somewhat less thereafter)

there was great wealth in a fairly large economic upper class, and there were

new cities, too. Every gymnasium

needed appropriate athletic, every library literary, every theater dramatic,

every school philosophical and literary statuary; every wealthy garden court

required garden sculpture. A

mechanical method called pointing had

been invented, probably in the second century B.C., to make accurate replicas

of famous "appropriate" masterpieces. It was easiest to copy bronzes: piece molds were made from

the originals (they could be shipped to workshops in the marble-producing

regions), plaster casts were made from the piece molds, measurements were made

off the casts for the pointing machine (the same device was used down to the

early twentieth century to help in making marble replicas); only the eyelashed

eyes and convoluted hollows had to be protected and could not be molded, so we

find that eyes and fluffy hair, for example, were done partly freehand. The best copies were made taking many,

many measurements; those for middle-class gardens, say, or to fill the niches

in a theater or bath, to be seen from a distance, might be quite

generalized. The very best copies

of bronzes were done in bronze, cast in molds off the plaster cast, but these

are just as rare as originals; mostly we deal with marble copies. When we have dozens of a single statue,

as with the Discus Thrower, we know that the good ones are pretty reliable even

though comparison with one of the rare originals, like the Cape Artemision god,

shows us how important the original master's finishing touches are in bringing

it to life, so to speak. So, the

fine composite cast in the Print is fully justified, and it helps us to imagine

the original; notice how important it is to have the legs unencumbered by the

tree trunk support that was necessary in marble. The small statuette copies, of course, were made

freehand, and cannot be dead accurate, but many of them are quite fine, and in

cases where none of the full-size copies is complete can answer questions about

the pose. The Discus Thrower seems

to have been designed to be set up, perhaps in front of a wall, to be seen

primarily from one side, in which we see the full spread of the arms, which tie

the composition together, and can look straight up into his face. Photography proved long ago that a real

discus thrower is at no single moment in just this position, just as a horse is

never in the "flying gallop".

This pose is not only finely designed to suggest both poise and energy

but to sum up the essentials of preparing to hurl the discus; in this respect

it is like the Cape Artemision god: a synthesis

of equilibrium in one case, of the act of discus-hurling in the other. Myron was famous for the realism of his

sculpture; we are flabbergasted to read that his most famous work was a great

bronze cow, and we wish we had written sources about ancient sculpture that

would tell us more from the artist's point of view, with fewer anecdotes about

fool-the-eye effects.

[MA 90] [A 68] [A 95] [A 458] At about the same date as the Discus

Thrower, which is to say right about the middle of the fifth century and right

on the borderline between Early Classical and Classical style (so that

either/or is a false choice) we have four very great statues, two original

bronzes discovered just over thirty years ago by sponge divers working near

Riace in south Italy and numerous copies in marble of two extraordinary lost

statues which were of bronze.

All of them have been discussed in connection with the name of Pheidias,

the most famous of all Greek sculptors, which is not to say that there

are any sound reasons for an attribution.

On the other hand, they are all three work contemporary with his youth

and they seem to be Athenian, so they tell us something of where he's coming

from, in one sense or another of that phrase, and it seems quite possible,

though not certain, that the Apollo copies in marble go back to an original by

the same sculptor as the Riace statue designated "Warrior A", the one

of which you have a print.

Riace Warrior A is more likely a semi-divine hero than a mortal warrior, but he held a spear and wore a shield on his left forearm. He stands in contrapposto with the free leg forward, as Athenian Early Classical male statues usually do. With the torso turned slightly to his left and his head and standing leg to his right, his whole stance is dynamic, expressive of physical and mental fitness. There were groups of ethnic heroes dedicated at Olympia and Delphi; this statue, and Warrior B which was found with it, having sunk with their ship before reaching Rome, may belong to one of those groups. Since the great sanctuaries seem not to have permitted the taking of molds for production of pointed copies, and the statue was lost to view in the shipwreck, that possibility would explain our having no copies of such a splendid statue. While the Cape Artemision god is still typical of Early Classical art, this statue is on the threshold of art with the attitudes and skills of the Periklean period of Athens and is quite unlikely to date earlier than ca. 450 B.C. The head and beard hair is now very elaborate (some of the curling tresses had to be cast separately). The eyes were inlaid; in this case, it is the quartz and colored material of the irises that has fallen out. As conservation experts cleaned the head a quarter century ago, they revealed under a coating of oxydized bronze the rarely preserved copper for pink lips and (!) the silver teeth; the aureoles of the nipples also were copper. With these imagine the bronze body not quite so dark as it is today (think of one of the stars of the Italia soccer team), and you will have a good idea of an original bronze statue.

Riace Warrior A is more likely a semi-divine hero than a mortal warrior, but he held a spear and wore a shield on his left forearm. He stands in contrapposto with the free leg forward, as Athenian Early Classical male statues usually do. With the torso turned slightly to his left and his head and standing leg to his right, his whole stance is dynamic, expressive of physical and mental fitness. There were groups of ethnic heroes dedicated at Olympia and Delphi; this statue, and Warrior B which was found with it, having sunk with their ship before reaching Rome, may belong to one of those groups. Since the great sanctuaries seem not to have permitted the taking of molds for production of pointed copies, and the statue was lost to view in the shipwreck, that possibility would explain our having no copies of such a splendid statue. While the Cape Artemision god is still typical of Early Classical art, this statue is on the threshold of art with the attitudes and skills of the Periklean period of Athens and is quite unlikely to date earlier than ca. 450 B.C. The head and beard hair is now very elaborate (some of the curling tresses had to be cast separately). The eyes were inlaid; in this case, it is the quartz and colored material of the irises that has fallen out. As conservation experts cleaned the head a quarter century ago, they revealed under a coating of oxydized bronze the rarely preserved copper for pink lips and (!) the silver teeth; the aureoles of the nipples also were copper. With these imagine the bronze body not quite so dark as it is today (think of one of the stars of the Italia soccer team), and you will have a good idea of an original bronze statue.

From

now on until the end of independent Greek civilization in this course, unless

I say otherwise (for there are exceptions) all architectural sculpture is both original and of marble; all freestanding statues shown in marble are

copies of original bronzes, and all bronzes in the

slides are original Greek bronze statues.

"The

Kassel Apollo", [A 68] is

the name of nearly 30 surviving copies, some of them statuettes but most of

them full size pointed copies, of a single famous mid-fifth-century statue of

Apollo: as a young god, he wears his long hair loose, the long hair at this

date, again, betokening the unchanging character of a god (but also due to the

influence of prexisting famous images).

It is named for the Kassel Musem in Germany, because this is the most fully

preserved fine copy, but the National Archaeological Museum in Athens has the

largest number of copies, two of them very fine. We do not have the original. The head in Athens

shown in the slide (the rest of this copy is lost) shows the mouth just open

and teeth inside, as on Riace A, and even in marble renders the long tresses of

hair very corkscrew-like. These

are precisely the features that in copies made at a distance would have to be

made up and rendered freehand, because when you take molds from the original

you must protect delicate parts like the eyelashes and inlaid eyes and you

cannot get molds of convoluted hollows as in the hair and the open mouth;

before taking the mold, such parts had to be covered with wads of lint. Copies of the "Kassel Apollo"

made of marble from Italy or Asia Minor (so made based wholly on molds) have

the mouth closed and have the heavy-lidded, almost Elvis-like eyes that the

Romans of the 2nd century after Christ preferred, but the Athens head of the

"Kassel Apollo" has eyes and eyelids shaped similarly to those of

Riace Warrior A. Evidently this copyist could look at

the original statue in rendering these details. Both the number of copies found around Athens and these

convincingly Classical details in the Athens copy of the head suggest that the

original statue stood in Athens before it was abducted. Some scholars think that it was one

that books mention, the Apollo Alexikakos,

"warder-off of evil", which was by Kalamis, a famous sculptor. Others think that both this Apollo and

Riace A are Pheidias. We cannot

resolve such contradictory possibilities, especially in this course. The reason that it is important to

mention and discuss them is that, although Greek art is largely anonymous to us,

it was not anonymous when it was made; we simply have lost most of the

information (during the upheavals and poverty of Late Antiquity and the Early

Middle Ages). Authors such as the

Elder Pliny and Pausanias give us long lists of names and titles and lots of

anecdotes about famous artists; we even have statue bases with signatures

without statues, as well as statues without signatures. It is as if we had the ceiling of the

Sistine Chapel and had lost all the links of evidence that would permit us to

attribute it to Michelangelo.

Ancient Greek artists, beginning in this period, were star personalities

just as in the Italian Renaissance.

A third, equally important and tantalizing bronze

masterpiece of the middle of the fifth century is the Athena [A 95] known

primarily from (a) an exquisite copy of the head in Bologna, Italy, (b) a pretty good copy with a belonging head of the

same type as Bologna (but not exquisite) in Dresden, (c) an excellent

copy without the head in Dresden,

and (d) a torso (skirtless, armless, headless) in Kassel in which the copyist

strove to express in marble the metallic scaliness of Athena's aegis. A century ago Adolf Furtwängler made the connection among

these copies. He also thought it

was the Athena dedicated by the people of Lemnos on the Acropolis in Athens,

which was by Pheidias; we doubt that identification today and prefer not

to use the name "Lemnia" for this statue-type. Even unnamed and unattributed, the

statue is no less beautiful and important; really knowing art and its history

is not truly a matter of knowing labels, although real knowledge to go with the

names we possess would be a boon.

Here, finally, we see a draped statue in contrapposto. It is

one thing to make mimesis of

the human body in movement, balancing and turning, quite another (much more

difficult) to imply such a body concealed by drapery and to make mimesis of drapery such that it

represents the response of the hanging cloth to the behavior of the

concealed body. No wonder it

happens in a freestanding statue, where it has to work when seen all the way

around, only about 30 years later than the "Critian Boy". Compare the drapery of the Bologna-Dresden Athena with that of

Athena standing behind Herakles on the metope from the Zeus Temple at Olympia

[A 90] only about 15-20 years earlier, or compare the Delphi Charioteer. This Athena's drapery implies

body action very similar to that of Riace Warrior A, only gentler for the young

girl goddess, without showing anything of the body beyond the hint of the knee

of the bent leg. Nothing in

figurative art is more difficult than what is done here; artists less than the

very greatest either betray awkwardness or resort to formulas in handling this

challenge. Athenians liked to

emphasize the girlhood of their goddess (although, like Apollo, she had once

been fierce). In this statue, as

on some vases, she is represented as the maiden warrior at peace: she leans on

her spear and holds her helmet to contemplate it, while her head is bare,

unprotected. Most Greeks have

springy, curly hair; the sculptor gives her a headband which emphasizes the

living springiness of hair by compressing it. He also draped her supernatural aegis like cloth diagonally and cinched it together with the

overfall of her peplos. He made the clump of folds pulled up

over the girdle under her right arm and the folds escaping from under the aegis under her raised left arm into

sculptural nodes with expressive power of their own. Here drapery moves beyond mere naturalism, from mimesis to poiesis, so to speak, as we shall see in the sculptures of the

Parthenon. These significant forms

of drapery do not stand for, do not equate to, something else, the way that the

aegis does (the aegis is Athena's supernatural protection, its origin so ancient

that we don't know how it originated); rather, their expressiveness is part of

what raises the statue from prose to poetry, from mere representation to

art. Even the copy of the head in

Bologna has inset eyes, so we may be confident that the original had. Notice that the Gorgon face on the aegis is still round-faced but no longer

has the fangs and lolling tongue of an Archaic Gorgon.

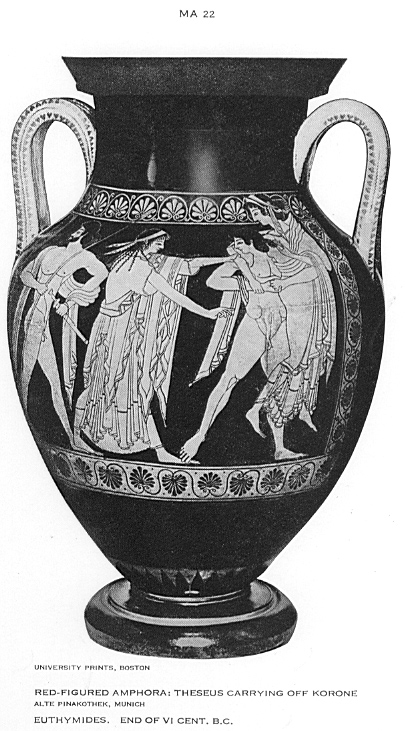

[MA 30]

The second slide shown in lecture shows the whole vase in the Louvre,

Paris. It is a calyx

krater, a taller, slenderer (more evolved) version of the same

vase-shape as Euphronios's krater with the Death of Sarpedon about a half

century earlier. The artist is

called The Niobid Painter after the

picture (on the less elaborately decorated side of the Louvre krater) in your

Print; this picture is certainly a quotation of a lost major painting of the

period, and so is the picture on the front of the vase, whether it represents

Odysseus's visit to the Underworld (Nékyia)

or the Argonauts (as older scholars thought). Neither of these pictures is like most of this

vase-painter's work; that is, the drawing is alike, so we know that it

is the same hand, but the compositions are not. His own compositions have the figures on one ground line, as

in earlier vase-painting, which, we must admit, makes for more coherent vase

decoration; in the pictures of the slaughter of the Niobids and the Nékyia the figures placed at differing

levels look like pale spots scattered on a black background, reminding one of

the large-flowered prints on black or navy blue of women's dresses in the

1930's, which is not so decoratively successful as one Euphronios's composition

of Sleep and Death lifting the body of Sarpedon. But imagine them in full color, with shading, and the dead

Niobid half hidden by her hillock makes sense. We can only guess that the vase-painter took the trouble to

make careful sketches of the wonderful new paintings and quote them on his vase

(which was exported, found in an Etruscan tomb) being either eager to emulate

such work or aware that the reproduction of a famous composition would be a selling

point. A Niobid painting done at

this time is recorded in Athens, and a Nékyia

was in the Clubhouse (Leschê) of the

Cnidians at Delphi; it was still there when Pausanias described it in the

second century after Christ. Both

of these murals are described as having the kind of innovations that the

vase-painting bears witness to--however unsuccessfully: for the Niobid Painter

is not good at foreshortening (see Apollo's shoulder) and the scrambled

overlaps in the scene on the other side of the vase suggest that he did not

truly grasp the rudimentary steps toward a real optical (i.e., how we actually

see) perspective, which the descriptions indicate was accomplished by mural

painters like Polygnotos of Thasos who worked now and were still famous

500 years later (just as Raphael and Michelangelo are today, nearly 500 years

after completing their works). The

Artemis (removing an arrow from the quiver on her back) gives us a simpler

rendering of exactly the same kind of drapery as we just studied in the Bologna-Dresden

Athena. The Niobid Krater is not

earlier than the 450's B.C.

The story is told by Ovid in the Metamorphoses, an ancient book that is just as pleasurable and interesting to read today as the day it was written, during the reign of Augustus (30 B.C.- 14 A.D.). Niobe boasted that, as the mother of seven fine sons and seven fine daughters, she was a better woman than the goddess Leto, who had only the twins, Artemis and Apollo; they, zealous for their mother's honor, slew all fourteen of Niobe's children, and Niobe was transformed into a great rock, from which water oozed perpetually: her tears never cease. This is a good example of a cruel and primitive myth, in which Artemis (as with Aktaion) and Apollo (shooting plague arrows as in Homer) are still vindictive, fierce gods, which Classical taste has modified to concentrate on the piteous fate of the innocent children and adolescents (the same kind of modification as in Classical drama); for the artist, it is wonderful--so many poses (some of which can be half-draped or nude), so many emotions, so many different ages of both sexes.

The story is told by Ovid in the Metamorphoses, an ancient book that is just as pleasurable and interesting to read today as the day it was written, during the reign of Augustus (30 B.C.- 14 A.D.). Niobe boasted that, as the mother of seven fine sons and seven fine daughters, she was a better woman than the goddess Leto, who had only the twins, Artemis and Apollo; they, zealous for their mother's honor, slew all fourteen of Niobe's children, and Niobe was transformed into a great rock, from which water oozed perpetually: her tears never cease. This is a good example of a cruel and primitive myth, in which Artemis (as with Aktaion) and Apollo (shooting plague arrows as in Homer) are still vindictive, fierce gods, which Classical taste has modified to concentrate on the piteous fate of the innocent children and adolescents (the same kind of modification as in Classical drama); for the artist, it is wonderful--so many poses (some of which can be half-draped or nude), so many emotions, so many different ages of both sexes.

[A 413]

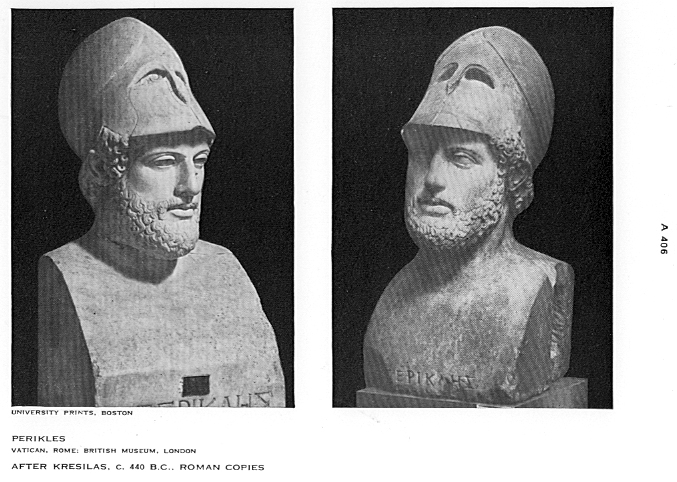

Another innovation of this period is the introduction of the portraiture

of statesmen, and literary men, too, not portraits for the tomb to house the ka as in Egypt but to be set up for

public edification, as we set up Lincoln in his Memorial in Washington

D.C. Indeed, in so doing, we are

heirs of the Athenian Greeks. We have

copies of only a few of the early Greek public portraits. Rarely, we have a full length copy (for

the Greeks portrayed the whole man, recognizing that his body language

was part of his essence), as of the poet Anakreon, but usually we have what the

Romans made most of: busts, which decorated their schools and libraries;

luckily, many of these, like the Themistokles

found in the excavations of Ostia, the port city of Rome, are inscribed to

identify them unambiguously. The

Romans, who traditionally had kept death masks of their ancestors enshrined in

their homes, had no problem with busts for portraits. The Themistokles does seem like a copy of Early Classical

work of the same date as the Olympia, Temple of Zeus, sculptures, but we need

to remember that the original was a full-length standing statue, as was the

famous Perikles to which we now turn, to discuss him in the next section.

Notice the slight tilt of the head in the unbroken and superior copy at right, in the British Museum.