Babylon, Persia, Saitic Egypt, Archaic Greece and Etruria

There are so many Prints for this period that I shall not be able to make additions, since the page would get too long for many computers, but you can find good images also on line. Google and Wikipedia will take you to them.

[G 28] By the end of the 7th century (612 B.C.),

as the syllabus describes, with the collapse of the Assyrian Empire, Babylon entered what has become the

period of her greatest fame, thanks to excavations a century ago and, not

least, to the stories of Babylon in the Hebrew Bible, though these stories are

not only biased but ill informed.

Culturally, the Neo-Babylonian period was indeed brilliant; it was also

brief, since the Persian king Cyrus captured Babylon in 538. The reconstruction drawings made by the

architects attached to the excavations give some idea of the grandeur of the

temple quarter. All we really know

of the Hanging Gardens is how famous they were, included in the Hellenistic

period list of the Wonders of the World.

[A 11, right pair: Kleobis and Biton]

Here is a good example of regional difference. This pair of statues are kouroi,

but only the kouros type is

like the Attic New York kouros. They are not at all blocky but fleshy

and rounded; their proportions are different; they have hair like the Dame

d'Auxerre statuette of ca. 640 and the little ivory kneeling boy from Samos of

about the same date; they also have the quasi-inlaid eyebrows, round eyeballs,

short noses, triangle-cornered mouths, angular jaws, wide-spread pectorals,

double-curving arch of the rib cage, trapezoidal pubic hair, large genitals,

short arms, and hands with large, square-tipped thumbs--everything, in fact,

that characterizes a male figure in the Daedalic style. Sixty years ago they already were

recognized as the last major works done in the Daedalic style. Notice that although they are more

natural looking than the New York kouros,

they are not to be dated later; on the contrary, their Daedalic character

requires dating them no later than necessary. The inscription on one of the bases is fragmentary, but

enough is left to be sure (1) that the sculptor signed his work

(----]medes of Argos), something that artists today take for granted, precisely because, beginning about now, the Greeks began to do so; this means that the statue had more prestige if it was signed by a highly regarded artist, so the artist was gaining status as more than a skilled workman, and (2) that the pair of statues was dedicated, at Delphi in the sanctuary of Apollo where they were found, by the city of Argos, since the sculptor was Argive. (Note that work found in all the great sanctuaries of Greece was brought there and dedicated by cities, and private citizens, all over the Greek world; there is no such thing as a Delphic style). As twin statues, therefore, they have been thought, ever since they were found, to represent the legendary paragons of filial piety of the city of Argos, Kleobis and Biton, who, when the oxen were not brought in from field work in time to be hitched up to take their mother to the great Argive Sanctuary of Hera for the goddess's festival, yoked themselves to the cart and got her there on time; they died of exhaustion as they slept in the temple (in a state of grace, to put it in Christian language). Since, also, Herodotus tells us in Book I of his Histories that the Argives set up statues at Delphi of Kleobis and Biton, the identification would seem as nearly certain as we can hope for. The statues have a magnificent presence and are over life size, but details such as their eyes and hair are very finely carved.

(----]medes of Argos), something that artists today take for granted, precisely because, beginning about now, the Greeks began to do so; this means that the statue had more prestige if it was signed by a highly regarded artist, so the artist was gaining status as more than a skilled workman, and (2) that the pair of statues was dedicated, at Delphi in the sanctuary of Apollo where they were found, by the city of Argos, since the sculptor was Argive. (Note that work found in all the great sanctuaries of Greece was brought there and dedicated by cities, and private citizens, all over the Greek world; there is no such thing as a Delphic style). As twin statues, therefore, they have been thought, ever since they were found, to represent the legendary paragons of filial piety of the city of Argos, Kleobis and Biton, who, when the oxen were not brought in from field work in time to be hitched up to take their mother to the great Argive Sanctuary of Hera for the goddess's festival, yoked themselves to the cart and got her there on time; they died of exhaustion as they slept in the temple (in a state of grace, to put it in Christian language). Since, also, Herodotus tells us in Book I of his Histories that the Argives set up statues at Delphi of Kleobis and Biton, the identification would seem as nearly certain as we can hope for. The statues have a magnificent presence and are over life size, but details such as their eyes and hair are very finely carved.

[G 64]

Now we turn to one of Greece's most venerated temples. Later referred to as the Temple of Hera, alone, it may have been

for both Zeus and Hera until the Early Classical Temple of Zeus near by was

built in the 460s B.C. It stands

in the sanctuary at Olympia, where

the Olympic Games were by the time of its construction about 175 years old, and

it replaced an earlier temple that had stood in exactly the same place; its

predecessor, however, did not have a colonnade around the cella. So long as

pagan religion survived, this temple was maintained and cherished; thus it

remained in use for about a thousand years. There are many questions about its architecture that we

cannot answer; except for a great terracotta ornament from the peak of the roof

(which you can see in the museum at Olympia), we have no parts of the

superstructure, nothing above the capitals of the columns, not even a

fragment. We assume that the upper

parts were of wood, which was still the traditional structural material of

temples on the Greek peninsula, perhaps especially in so ancient a sanctuary as

Olympia. We know that the original

columns were wood (Pausanias who wrote in the middle of the second century

after Christ saw a surviving oaken column in the back porch of the temple, and

the stone columns which we see are all different and of widely different

dates), and wood columns could not have borne a weightier superstructure (the

superstructure is called the entablature). We know that above the orthostats, the cella walls were of mud

brick, because the top surfaces of the orthostats are not fixed to take courses

of ashlar above. Considering that

Corinth had built an all-stone temple with terracotta tiles for the roof (but

without any columns) in the seventh century, and would very soon build [A 46]

an all-stone colonnaded temple at her colony on Korkyra (Corfu), the use of

traditional materials for the Hera Temple at Olympia, ca. 600 B.C., was

conservative. The plan of the

temple, on the other hand, is up to date and sophisticated. In the cella, instead of a row of columns down the middle to support the

roof, the need to reduce the span of the roof beams was met by columns on both

sides of the cella interior, near the wall. Thus, entering the door, one had a clear view of the statue

at the opposite end of the cella; these interior columns also give the interior

rhythm and a sense of scale, so it won't be just a vast, dark box. The peristyle

(exterior colonnade), in the case of a temple with a mud brick wall, protected

it from rain; what is remarkable here is an innovation in the spacing of the

columns: subtly closer together towards the corners of the temple. This is called angle contraction, and it

indicates that the lost superstructure had a proper Doric frieze, consisting

of alternating triglyphs and metopes, which we shall see in

the next temple: one needs to adjust the spacing of the columns in order to

have triglyphs meet at the corners.

In fine, both the Doric Order and the Ionic Order took their

design elements from traditional wooden forms (remember our seeing the bundled

column with a bud capital in Egypt in a wooden model in Dynasty XI and in a

stone temple in Dynasty XVIII) and recast the traditional forms in terms

of building in ashlar stone. The

architects recast them so thoroughly that it is impossible to

"translate" the stone forms back into wooden construction, even

though some things are obvious, such as that guttae derive from dowel pegs.

[A 46]

Corinth had a colony on the lovely island (find it on the map opposite

the present border between Greece and Albania) of Korkyra, often called by its Italian name, Corfu. It was

prosperous, and early in the sixth century built a state-of-the-art temple in

the Doric Order, dedicated to the goddess Artemis, that is the earliest known

to us (a) built entirely of stone, with a stone peristyle, and (b) with stone

sculpture in its pediment. Any structure with a pitched roof must

have either gables or a hip roof; if it has gables, they may be open (but birds

and bees build nests in them, and rain gets in) or closed; if closed they may

be blank, or the back wall may be concealed by decoration. Pedimental sculpture in closed

pediments is what the Greeks preferred, from this time forward, for their

temples. The Corfu pediment has

the Gorgon Medusa in the center,

flanked by her children sired by the god Poseidon: the wingèd horse Pegasus (only Walt Disney gives him a

whole family of baby pegasoi, in Fantasia)

and the hero Chrysaor, both only

partly preserved. Flanking this

group are heraldic cats; since they have spots, leopards might be intended (if

the artist had heard tell of African spotted cats), but art historians call the

Archaic cats "panthers" unless they have male lions' manes. Left and right of the panthers, in the

corners of the pediment, quite small, are gods in battle (the one with a

thunderbolt must be Zeus). The

artist who composed this pedimental composition did not yet address three

challenges that will have been met a hundred years later, when, as in Greek

drama, also in the fifth century, they will strive for Unities: Unity of Scale

and Unity of Subject Matter; also, they will avoid heraldic symmetry. It is indeed a challenge, because the

low, wide triangle with very acute angles (constricted space) at the sides is

one of the most difficult shapes to compose coherent pictures in. Notice, too, that this pedimental

sculpture is in half-round relief; before the end of the sixth century,

pedimental sculptures will be carved fully in the round and set into the

pediment, fastened with strong metal pins to the back wall and secured in

cuttings in the floor of the pediment.

Yes, its floor; the pediment of the Parthenon, for example, is deep

enough that one could sit up there and have a picnic without fear of falling

(being much smaller than the sculptures).

The Corfu pediment is still shallow, and the moldings (geisons) framing it are not yet like

what we shall see on Classical temples.

But it is very perfect in its own way. The Gorgon indeed is carved with such almost metallic

crispness and in such fine detail that we are led to suppose that, in this

early effort, the sculptors did not yet realize, had not yet considered, that,

from the ground, such delicate detail could not be seen. The pediment is dated ca. 580, so the

temple may have been initiated a decade or two earlier; the dating of the

pediment is derived from comparing the Gorgon with Corinthian vase-painting of

the early sixth century (which is dated on intricate grounds that you may study

if you take Art 4409) and the head of Chrysaor with the statue to which we now

turn, but in the latter case it is this temple, once we have it dated, which

dates the statue that is developmentally comparable.

[A 24]

The kore from Keratea, some miles from Athens in Attica, now in the

Berlin Museum, is our first sixth-century maiden statue. Kore

(which is Persephone's name, as the daughter of Demeter, and still means daughter in modern Greek) is the

feminine form of kouros; the plural

is korai. Like the kouros,

the kore statue has its roots in the

seventh century; not only is the Dame d'Auxerre a proto-kore but we even have a full size statue of similar type (too badly

battered to be easily appreciated).

As with the kouros, however, the great series of

real korai is a hallmark of

sixth-century Greek art. The

maiden from Keratea was once thought by many to be a goddess, because of her

cylindrical headdress and the pomegranate; thirty years ago, however, an Attic kore of ca. 550 B.C. was found, and we

have her inscription (with her name, Phrasikleia), which tells us that death

took her before she could be married--and she is dressed the same way as the

Keratea girl, also with jewelry, also wearing red, so evidently these are girls

dressed as the brides that tragically they never were to be, just as the kouroi are beardless: adolescent ephebes or doing military service (one

married only afterward). Although

one is Corinthian and male, the other Attic and female, the facial structure

and proportions of the Keratea kore

and Chrysaor at Corfu are so alike that they are generally thought to be

contemporary. In any case, she

falls between the flat-eyed, flat-cheeked New York kouros [A 443] and the Calfbearer [A 19] both of which, like her,

are Athenian work. It is wonderful

to have a statue like this one with so much of the color preserved, reminding

us that Greek sculpture (as

distinct from neo-Classical) was never

chalky white and in the Archaic period was very vividly colored, though they

seem always to have left the flesh the off-white of the marble, for both sexes (for limestone

sculpture, which was coated with gesso and painted, just as it was in Egypt,

the males were red-brown and the females pale, following the ancient color code). Notice the loving attention the

sculptor gave the finger and toe joints and nails; long before artists can

master the organic whole of the entire figure, they can lavish care and close

observation on the small parts. I

have saved the most remarkable detail in this statue for the last: it is an

epoch-making innovation. Most of

her drapery is just done with ridges and grooves, as we have seen occasionally

in Egypt and Mesopotamia, and to show her feet the artist just cuts out an arch

to expose them. But look at the

ends of the shawl! It seems to us

such an obvious thing to do, show the actual folds with a zigzag, but here it

is done for the first time in the

history of the world (unless an earlier one should turn up tomorrow);

the artist has shown cloth behind cloth, cloth lying over cloth, to show how

many times the shawl is actually folded; he is showing its three-dimensionality

structurally, so we can count the folds and see the tassels on both

corners. If this were just an

experiment with no future, it would not matter so much; it would be in a class

with those occasional Egyptian experiments with a face drawn in three-quarter

view--mutations without progeny.

But from this beginning, they will continue experimenting; look ahead to

[A 27] and [MA 22]; a person born ca. 590 who lived to ca. 510 would have seen

that whole development in the works all around him or her. We shall see more change in those 80

years in Greece than we have seen in the whole 2,500 years (so far) of Egyptian

art. Good or bad? Simply a fact.

Greek

art is different because it is the beginning of western art as we know it, art

in which change is largely artist-motivated, art for a society that begins to

be interested in art for the thrill or quiet satisfaction of looking at it,

that does not expect it to be magic or replace the perishable body or appease

potentially angry gods. The

families who place a kouros or a kore either on the tomb of a beloved child or as a votive statue in a

sanctuary, as on the Acropolis in Athens, are vying with each other to see who

can set up the finest and most admired statue. They intend for their fellow citizens to admire them and

envy them, grave statues included; now, like the great cathedrals of Europe

later, Greek sanctuaries and even cemeteries begin to function somewhat as

museums, too. After all, is it not

like dedicating a memorial stained-glass window in your church? Doesn't one expect everyone to admire

it? Does it not boost your social

standing? This is the secular and

social function of much religious art from now on.

[A 19]

If we wish to study a kouros a

generation after the New York Kouros and Kleobis and Biton, not far in date

from the Keratea Kore, we find that there is, unless one turns up tomorrow,

none of the same quality and state of preservation. The Moschophoros (English: Calfbearer) from the Athens Acropolis (and ,like the other Acropolis

sculptures, on view in the Acropolis Museum), however, is a masterpiece and

will serve just as well: he is older, he wears a cloak, and his arms hold the

newborn calf that is an offering to the goddess--all traits that depart from

the kouros type, but his legs in the

striding position, his frontality, and the exposed anatomical parts are all

comparable. Like the Keratea Kore,

he has tremendously muscular, massive arms and shoulders (this massiveness is

favored in some Athenian workshops and at some times more than others), and he

is far less four-sided than the New York Kouros. The organization of the planes of his face, his smaller eyes,

his less emphatic mouth all suggest that he could be as much as a decade later

than the Keratea Kore (note that now we talk of decades rather than centuries

and millennia; as we discuss the chronology, thus do we inform you how to study

it). The sculptor uses beads for

the hair (most Greeks have curly or wavy hair, so the beads serve pretty well),

but they no longer could be mistaken for a wig. It is an expensive statue, fully lifesize and with inlaid

(rather than painted) eyes. Its

masterly quality resides in the coherence of the parts (it all hangs together)

and in the artist's making design sense out of what would be in life an

awkward, visually confusing composition: a new calf, all legs and joints,

draped around a man's shoulders.

The dumbest assumption we can make about this art is that

"natural≈better"; no, the very dumbest is that "more

detailed≈better".

[A 22]

Not all kouroi and korai are Athenian or even from

peninsular Greece. Indeed, the

most important temple of this generation, arguably, was the Rhoikos Temple

(named for its architect), the third

of four successive Temples to Hera in the greatest of her sanctuaries, that on

the Ionian island of Samos (on [MAP

2], it is the island nearest the coast between the coastal Ionian cities of Ephesos

and Miletos). Only copyright law

prevents our having it in the University Prints. We must take note of it because Rhoikos and Theodoros of

Samos, in this temple, first used stone-cutting lathes for making the bases of

Ionic columns, and here for the first time we know that there was an

Ionic capital with a volute across it (the earlier Samos Heraion already had

the deep prostyle porch of an Ionic

temple plan). The Archaic temples

of Ionia, here on Samos and a little later at Ephesos and Miletos, not only are

the largest, most expensive temples of the sixth century B.C. in Greece but

also the places where some of the masons and stone carvers drafted by the

Persian king to build Persepolis (look ahead to [O 408, ff.] in your Prints) had learned their craft. So the amazing quality of the statues

dedicated to Hera on Samos in the generation of the Rhoikos Temple is perfectly

consistent with the wealth and brilliance of this, one of the loveliest, best

watered Greek islands. In the 19th

century, the Louvre called its statue "Hera", mistakenly thinking

that a statue dedicated to Hera (as the inscription tells us this one is, by a

citizen named Cheramyes) would be a Hera, just as some kouroi dedicated to Apollo (inscribed)

led to museums' calling all kouroi

"Apollos". Since then

finds in many sanctuaries have settled the question: in sanctuaries, the

statues of girls and boys are set up by their parents as votaries of the

deities in question--and to show off

wealth and social status, just as debutante balls and quinceañeros are staged for the same purpose. The Louvre Kore of Cheramyes, in fact, has a sister, literally her sister, from the same family dedication (the

Samians who could afford to set up statues of the whole family in a row on one

base!), now in the Berlin Museum. The Louvre girl has a cloak, the Berlin

girl none, but she holds a pet rabbit; I suppose she is the younger daughter,

whereas the Louvre girl has put away childish things, such as pets. Both bear Cheramyes' dedicatory

inscription. Until recently we had

no good idea what Samian heads of this period looked like (the primitive

feeling that carved faces harbor a personal force has led to their destruction

in many places), but recent excavations have produced kouros statues with heads; the faces are rounded and plump and

smiling. Cheramyes' dedication

(the korai in the Louvre and Berlin

survive) dates from about 560 B.C.; notice that the Ionian Greek sculptor is

less interested in articulation (how the parts fit together) than the Athenians,

but he was more interested in showing a girl's softly rounded bodily form and

his skill in a sensuous detail: how knuckles look with soft wool wrapped over

them. One of the most remarkable

things about ancient Greece to us is that, without political unification under

a central government, the Greeks were always keenly aware of being one people;

at the same time, each city state (polis)

had its own particular institutions and artistic traditions.

In the Print [G 59] showing the former reconstruction of the Siphnian Treasury at Delphi in the Old Delphi Museum, a very large votive sphinx (far larger than those that come from grave stelai) faces us. I am showing you slides of her taken in the New Museum, sitting on her volute capital, an early Ionic capital (columns were not used only in buildings); the sphinx was dedicated by Naxos, the largest of the Cyclades Islands, as we know not only from written evidence but because it is made of Naxian marble, about 560 B.C. Naxian style (note the face of the sphinx) is somewhat sharper and crisper than Samian, but the capital of the sphinx shows you what an early Ionic capital looks like.

In the Print [G 59] showing the former reconstruction of the Siphnian Treasury at Delphi in the Old Delphi Museum, a very large votive sphinx (far larger than those that come from grave stelai) faces us. I am showing you slides of her taken in the New Museum, sitting on her volute capital, an early Ionic capital (columns were not used only in buildings); the sphinx was dedicated by Naxos, the largest of the Cyclades Islands, as we know not only from written evidence but because it is made of Naxian marble, about 560 B.C. Naxian style (note the face of the sphinx) is somewhat sharper and crisper than Samian, but the capital of the sphinx shows you what an early Ionic capital looks like.

[MA 17]

We have not yet looked at Archaic vase-painting. By the 560s B.C., the Corinthian

industry was in trouble, and the Attic potters were no longer farouche experimenters. To state simply changes that occupy us

for several weeks in a course devoted to Early Greek Art, by the second quarter

of the sixth century we have had real (not proto-) black-figure technique for a whole generation, and Athenian

vase-painters have mastered everything that they could learn from the

Corinthians: how to marshall figures in neat friezes, how to avoid mixing

incised details with details rendered in other techniques--in a word,

professional discipline. The

mature black-figure technique will prevail until near the end of the sixth

century.

Like the Late Protocorinthian Chigi Olpe [MA 13] the François Vase comes from an Etruscan tomb and, like it again, it is an exceptional piece, not typical of its time even though that time is a great period in vase-painting. It is called after the Italian archaeologist, Alessandro François, who spent half his life finding all its pieces and putting together the jigsaw puzzle; it is a volute krater; a krater with volute handles is new; they look alien to clay (hard to make of clay) and probably in fact derive from bronze volute kraters; cf.[MA 89]

The François Vase with its two hundred neatly inscribed figures and fascinating subject matter and double signatures (each twice: "Ergotimos made" and "Kleitias drew", with "me" or "it" understood) and great size is so stupendous that we are prone to overlook the most important thing of all, especially for a course like this one: a basic change in taste. Like the kouros in [A 14] and the rider in [MA 41], all of the figures, including the animals and the miniature figures on the foot, express a new ideal in physical beauty, trim and neat and slender and sprightly; this is the new ideal of the middle third of the sixth century, especially in peninsular Greece (art of the Cyclades and of Ionia had never been massive like the Calfbearer and the Keratea Kore, anyway). Notice that such a change has nothing to do with any kind of progress or evolution; it is a change in attitude, like the change in our own century from Modern to Post-Modern. Other changes, such as evidence of increasing knowledge of and ability to incorporate the anatomy of the human body and three-dimensional drapery, also continue, independent of the change in taste.

Like the Chigi Olpe the François Vase may be related to paintings with similar subject matter, and drawn at a not much larger scale, done on gessoed wooden panels and dedicated in sanctuaries. But wood usually does not survive in Greece, so the hypothesis cannot be tested against any evidence. Similarly, I cannot test my suspicion, based on our having very few pieces of vase-painting by Kleitias, that he himself may have spent much of his working life doing paintings on something other than vases. Not that in this period vase-painting was an inferior medium. We think of "painting" as having light and shade, and landscape or room interiors in the background, and emphasizing the play of brushstrokes, but from literary sources relating to the fifth century we know that trying to show roundness by shading began only then, so a better parallel, technically, for the lost paintings of sixth-century Archaic Greece would probably be the colored outline of Egypt, as in the Tomb of Nakht.

The main scenes on the François Vase relate to the hero Achilles in the Trojan Epic Cycle (only part of which is actually in the Iliad and Odyssey). On your Print, showing one side of the krater, on the lip is the Calydonian Boar Hunt, in which Peleus, Achilles' father, participated; on the neck are the Funeral Games in Honor of Patroklos, Achilles' friend and comrade in arms, who died at Troy (Iliad, Book XXIII); in the main frieze, all around the vase is the procession of the gods themselves attending the wedding of Achilles' parents, Peleus (who was mortal) and Thetis (who, as daughter of Nereus, was immortal and divine, thus expressing the feeling that there is something divine about a hero); in the frieze below the handle roots is the Death of Troilos--Troy would not fall while he lived, and Achilles lay in ambush until the boy came to water his horses at the fountain house; the animal frieze below is purely decorative. You can just see on the left, on the handle, if you know what is there, a hero bearing the body of his comrade off the battle field. Finally, on the foot, a miniature battle of miniature scope. Among the post-Homeric poems in epic style are playful miniatures, like "The Battle of the Frogs and the Mice"; if you have a very small frieze, therefore, you want to draw a very small epic; on the foot of the François Vase we find the "Battle of the Pygmies and the Cranes" (this is not the only time it occurs in Greek art, so we know that Kleitias didn't just make it up). The pygmies ride goats, being too small for horses. Do not make the mistake of taking this for bad anthropology. Any knowledge they had of the real small forest people of western Africa was at many removes from first-hand knowledge; it is like their knowledge of Central Asia, where they put the Amazons. What it is instead is a bit of artistic and literary sophisticated play.

Like the Late Protocorinthian Chigi Olpe [MA 13] the François Vase comes from an Etruscan tomb and, like it again, it is an exceptional piece, not typical of its time even though that time is a great period in vase-painting. It is called after the Italian archaeologist, Alessandro François, who spent half his life finding all its pieces and putting together the jigsaw puzzle; it is a volute krater; a krater with volute handles is new; they look alien to clay (hard to make of clay) and probably in fact derive from bronze volute kraters; cf.[MA 89]

The François Vase with its two hundred neatly inscribed figures and fascinating subject matter and double signatures (each twice: "Ergotimos made" and "Kleitias drew", with "me" or "it" understood) and great size is so stupendous that we are prone to overlook the most important thing of all, especially for a course like this one: a basic change in taste. Like the kouros in [A 14] and the rider in [MA 41], all of the figures, including the animals and the miniature figures on the foot, express a new ideal in physical beauty, trim and neat and slender and sprightly; this is the new ideal of the middle third of the sixth century, especially in peninsular Greece (art of the Cyclades and of Ionia had never been massive like the Calfbearer and the Keratea Kore, anyway). Notice that such a change has nothing to do with any kind of progress or evolution; it is a change in attitude, like the change in our own century from Modern to Post-Modern. Other changes, such as evidence of increasing knowledge of and ability to incorporate the anatomy of the human body and three-dimensional drapery, also continue, independent of the change in taste.

Like the Chigi Olpe the François Vase may be related to paintings with similar subject matter, and drawn at a not much larger scale, done on gessoed wooden panels and dedicated in sanctuaries. But wood usually does not survive in Greece, so the hypothesis cannot be tested against any evidence. Similarly, I cannot test my suspicion, based on our having very few pieces of vase-painting by Kleitias, that he himself may have spent much of his working life doing paintings on something other than vases. Not that in this period vase-painting was an inferior medium. We think of "painting" as having light and shade, and landscape or room interiors in the background, and emphasizing the play of brushstrokes, but from literary sources relating to the fifth century we know that trying to show roundness by shading began only then, so a better parallel, technically, for the lost paintings of sixth-century Archaic Greece would probably be the colored outline of Egypt, as in the Tomb of Nakht.

The main scenes on the François Vase relate to the hero Achilles in the Trojan Epic Cycle (only part of which is actually in the Iliad and Odyssey). On your Print, showing one side of the krater, on the lip is the Calydonian Boar Hunt, in which Peleus, Achilles' father, participated; on the neck are the Funeral Games in Honor of Patroklos, Achilles' friend and comrade in arms, who died at Troy (Iliad, Book XXIII); in the main frieze, all around the vase is the procession of the gods themselves attending the wedding of Achilles' parents, Peleus (who was mortal) and Thetis (who, as daughter of Nereus, was immortal and divine, thus expressing the feeling that there is something divine about a hero); in the frieze below the handle roots is the Death of Troilos--Troy would not fall while he lived, and Achilles lay in ambush until the boy came to water his horses at the fountain house; the animal frieze below is purely decorative. You can just see on the left, on the handle, if you know what is there, a hero bearing the body of his comrade off the battle field. Finally, on the foot, a miniature battle of miniature scope. Among the post-Homeric poems in epic style are playful miniatures, like "The Battle of the Frogs and the Mice"; if you have a very small frieze, therefore, you want to draw a very small epic; on the foot of the François Vase we find the "Battle of the Pygmies and the Cranes" (this is not the only time it occurs in Greek art, so we know that Kleitias didn't just make it up). The pygmies ride goats, being too small for horses. Do not make the mistake of taking this for bad anthropology. Any knowledge they had of the real small forest people of western Africa was at many removes from first-hand knowledge; it is like their knowledge of Central Asia, where they put the Amazons. What it is instead is a bit of artistic and literary sophisticated play.

[A 14]

Now, if we return to Corinth, we can see in a famous kouros (one of the first discovered;

that is why the old nickname, "Apollo", has tended to stick to him)

the same basic change in taste as in the figures on the François Vase. The Tenea Kouros takes its familiar name from the village near Corinth,

Tenea, where it was found; it was almost certainly the grave marker of a young

man. It takes only a couple of

moments to grasp that this kouros

embodies the same sprightliness as we saw in the figures on the François Vase;

that the sculptor also knows more about anatomy and how to carve marble to

suggest soft, breathing flesh than we have seen before; that the Tenea Kouros

is not Athenian--for example, the hair is stylized like a soft washboard. Balancing all that mass of marble on

such very slender ankles and tiny feet is really audacious.

[MG 363]

The elegance of the Tenea Kouros prepares us to find at Corinth the most sophisticated of all

Archaic Doric temples completed in the mid-6th century. Excavations since the label on your

Print was written (always remember that the University Prints are, literally, stereotyped; they can't just

change the label on the computer) have shown that the foundations were laid no

later than ca. 560 B.C. Today only

seven monolithic columns still stand, at the west (rear) end of the temple, but

before a 19th-century earthquake there were eleven, and an old engraving shows

them, and the entire plan is attested to because, instead of having had to dig

deep to bedrock and lay many courses of masonry to ensure that the stylobate would remain stable and the

columns would always stand without tipping (the stylobate was slightly domed

and the columns were made to tilt very slightly inward, as in later Classical

temples), here on Corinth's Temple Hill, which is an outcrop of sold limestone,

the Corinthian builders had to make cuttings in the living rock to receive the

levelling courses, and these cuttings remain visible. The surviving columns give us the intercolumniations

(distances between column center and the next column center), so the whole plan

can be calculated. The temple is 6

X 15 columns, which is long proportions, but, look, it has two cellas, back to back, requiring the

extra length. Thus, too, each

porch with columns in antis

is a pronaos (front porch) rather

than an opisthodomos (back

porch). In both cellas, there is a

central space with columns at both sides, forming the interior Order. It is typical of Archaic temples to

have monolithic column shafts, and in earthquake-prone Corinth it is also

common sense. In the capitals, the

echinus is still very broad, but not

pancake-like, as at Corfu a generation earlier, and the columns themselves are

slenderer and more widely spaced.

Although the frieze of triglyphs

and metopes is lost (doubtless a

victim of the lime kilns of medieval and early modern Corinth), we are

confident that it existed, because on the face of the architrave block that is in

situ, and visible in the Print, we see carved in relief the taenia and one regula with guttae plus

half each two more regulae. In Doric Order design, the regulae line up, one under each triglyph [see G 58 and G 37]. When a Doric building is complete, we

read the taenia and the regulae (as we are meant to) as part of

the frieze, but in construction in stone it makes good sense to carve

them in one piece with the architrave. Students who know some Latin will

notice that some of these terms are Latin words; this is because, like the

architects of the Renaissance, we take for our basic authority the Roman

architect and writer, Vitruvius (he lived in the time of the emperor

Augustus). The Corinth temple is

built of the local limestone (building whole temples of marble was not yet

customary); as usual, this was coated with a fine stucco made of marble dust,

which sealed the surface and made it gleaming white. Architectural details were painted in bright colors, just as

details were in Archaic sculpture; for example, the taenia was always bright red, the triglyphs and regulae

midnight blue or black. If this

seems gaudy, remember that the bright, dry air of Greece tends to

"bleach" color.

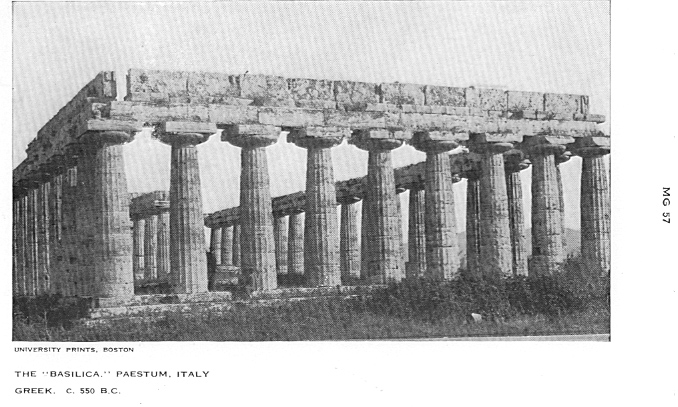

[MG 57]

At Paestum, south of Naples,

the Old Hera Temple (ludicrously

nicknamed "Basilica") sits

right beside the New Hera Temple (nicknamed "di Nettuno", Italian for

Poseidon, just because Poseidonia is the original Greek name for Paestum). Most architectural historians date it

as late as ca. 530 B.C., a generation later than Corinth, since, obviously, in

the absence of records, we must date things by their latest traits. The earliest trait of this

temple, a row of columns right down the middle

of the cella (so, where do you put the statue?), had been outmoded since ca.

600 B.C. We emphasized that

"colonial" (as at Corfu) does not necessarily imply

"provincial" in the sense of being less sophisticated and somewhat

backward, but in the western colonies, in south Italy and Sicily, we

find both interesting regional traits and backward and awkward

traits. In the

"Basilica" at Paestum, decoration on the underside of the echinus and the strong swelling profile

of the columns are regional traits, but the columns down the middle of the

cella and the very flat, broad echinuses are old-fashioned while the

construction of the frieze is inept; notice too that this temple has nine columns across the front.

[A 38]

Returning to Athenian sculpture, we should understand that sphinxes from grave stelai, like the

one from Spata in your prints or one, even finer, found built into the

Themistoklean wall in Athens, can be compared with kouroi and korai; they

have human heads, and the change to a slender, springy anatomy affects their

feline bodies just as it does anthropoid bodies. In this period, the sphinxes do seem to have slightly larger

eyes at any given date than mortal figures or those of the gods. Also, when we have the entire grave monument,

and the figure of a deceased youth is carved in profile view on the shaft, he

looks almost exactly like a kouros of

comparable date viewed from the side.

[MA 41]

On the Acropolis in Athens, there were fewer Archaic kouroi than korai, but we have parts of several riders, exceptionally expensive

sculptures, dedicated by the families of young men. Owning fine horses then was like owning an Italian sports

car now. The fragmentary sculpture

known as the Rampin Rider (the

original head was taken to France in the 19th century and is in the Louvre; the

fragments of his body and the horse were excavated later and are in the

Acropolis Museum; the join of the head and body was made 60 years ago, and

today the Louvre has a plaster cast of the body, Athens a plaster cast of the

head) is the most interesting of these riders; some have wondered whether it

might not be one of the sons of Peisistratos himself, the date (middle of the

sixth century) being about right.

The youth wears the wreath of an athletic victor. It is Athenian work showing development

comparable with the Corinthian Tenea Kouros (the dating on the Print is too

late). Evidently, the main view of

the statue had us looking at the horse's left flank; for that reason, the youth

turns and tilts his head, towards the viewer. In a kouros

statue, the head never turns; here we even have a slight turn of the

shoulders. Because the youth is

mounted, shifting the head and shoulders does not entail shifts in the spine,

pelvis, and knees, as it would in a standing statue that has to be balanced

around a plumb line. When we look

at the head alone, we see how refined the carving is, how gracious and elegant

the whole expression of the head; this statue is the epitome of

mid-sixth-century sprightliness; it is so fine that only gradually do we

realize that the eyes are still rather large and flat and that the corners of

the mouth are still rendered with little triangles--a warning not to date it

too late just because it's so good.

[MA 19] [1505] The art of Athens in this phase of Archaic art, from about

540 to about 525 B.C. is best exemplified by the art of the greatest of all the

Attic black-figure vase-painters. Exekias was also the potter of his

vases, and as such invented (on the evidence) three new vase shapes, or new

models of basic shapes: a new model of the one-piece amphora, like the Vatican amphora [MA 19 is drawings from

it], a new kind of broad drinking cup, which we call the Type A kylix [1505 is the inside of the bowl of

his famous kylix in Munich], and the calyx krater [MA 74, second row, at

left], a shape that we shall study in a later example. He signed his vases several times, in

beautiful lettering, with both the verb-forms, "drew me" and

"made me", and it is true that the shapes of the vases are just as

fully masterpieces as the drawing on them. He also introduced a new kind of inscription, in which the

name of a popular boy (or more rarely a woman) is followed by the adjective kalos; like the French beau, this word implies "fine"

in all respects: good as well as handsome. Kalos-names are

useful to art historians, because a boy had that sort of popularity for less

than a decade (not before puberty, and not once he was of an age for military

service and thereafter eligible to marry), so all vases praising the same boy

(sometimes a person who in middle age was a well known man) are closely

contemporary. The youth whom

Exekias praised was Onetorides.

Although many Greek vases have a principal side with an obviously more

important picture, great vases like the Vatican Amphora of Exekias have two

equal, original pictures. The

story of Ajax and Achilles playing a

board game during the long siege before the walls of Troy is not in the Iliad; it was in one of the lesser epic

poems. It makes a wonderful

subject for Exekias. First, the

equilateral triangle of the composition, countered by the inverted triangle of

their spears and varied by Ajax's helmet on his shield and Achilles' on his

head (making him dominant).

Second, the epic nature of the characters justifies Exekias's giving

them elaborate shields and densely embroidered cloaks; this dense-packed

elegant incision (also on their beards and on the horsehair crest of Achilles' helmet)

virtually makes an intermediate tone, setting off the pale background and the

solid black areas; this is a new, artistic use of incision. Third, the absence of physical activity

in the scene permits us to concentrate on that which Exekias is the first

artist (known to us) to really do: he conveys the psychology of the two

legendary heroes as he conceives it by the way that he draws, in a way

radically different from expressing grief, for example, by open mouth and

tearing of hair and abandoned gestures.

Here we move from melodrama to tragedy--and earlier than the birth of

Athenian tragedy in the theater.

Achilles is confident, relaxed.

Ajax is tense: he has an eyebrow drawn with two short straight lines,

his left arm is folded tight and he grips his spear tight, and the tensing of

his leg muscles is expressed by the heel lifted off the ground; also, he is

hunched over and on the edge of his seat.

The scene on the other side shows an everyday event in the life of the Dioskouroi ("Zeus's boys",

known in Latin as the twins, Gemini),

Kastor and Polydeukes, born from an egg that Leda laid when Zeus, in the form

of a swan, impregnated her; the adult male at the right of the picture is her

husband, Tyndareus, the boys' putative father. Greek boys (like their Cajun counterparts) entertain

themselves by going hunting; here the Dioskouroi are returning from a hunting

expedition, are welcomed home by Leda and Tyndareus, as well as the family dog

and a small servant boy (in Archaic art, children are still drawn like small

adults). This picture exists for

its own sake; it is pure charm. We

already have compared the Peplos Kore with Leda. Polydeukes, reaching to let the dog lick his hand, is like a

kouros statue come to life, a little

more developed than the Rampin Rider, a little less so than the Anavysos

Kouros. Exekias's beautiful horse

makes us realize how great is our loss in having so little of the Rampin

Rider's horse. And look at

Tyndareus's drapery! Men had long

worn mantles (himatia) wrapped diagonally,

but heretofore they were drawn flat; Exekias indicates the diagonal folds and

shows just how it is draped. This

is another important breakthrough.

Although Exekias was primarily a painter of large vases, the Munich cup [1505] is perhaps his most famous piece, because of the unique and original picture of Dionysos in a boat. The whole inside of the bowl is coated with a special glaze that we call "coral red", which provides the effect of the "wine-dark sea" and sets off the white of the sail. The story was that the god of wine, Dionysos, desiring sea passage sought it of Tyrrhenian pirates (Greeks called "Tyrrhenian pirates" those who called themselves "Etruscan merchants"). As they sailed, the Tyrrhenians began to feel that their passenger was too spooky and should be disposed of, overboard. Dionysos, being divine, knew their thoughts and, by his power, transformed the mast into a living grapevine, seeing which the Tyrrhenian pirates, in insane fear, themselves jumped overboard; Dionysos kindly turned them into dolphins, leaned back, and continued his voyage. It is a Just-So Story: Why the Dolphin Follows Ships at Sea. As with so many of Exekias's pictures, this is a rare subject in Greek art, and no other version is so fine as this. There is nothing superfluous, but the whole story is here, yet it is also a masterpiece of pure design, a perfect composition in a circular frame, with both the vine and the dolphins nearly enough symmetrical to fulfill decorative requirements but freely enough disposed to seem alive.

Although Exekias was primarily a painter of large vases, the Munich cup [1505] is perhaps his most famous piece, because of the unique and original picture of Dionysos in a boat. The whole inside of the bowl is coated with a special glaze that we call "coral red", which provides the effect of the "wine-dark sea" and sets off the white of the sail. The story was that the god of wine, Dionysos, desiring sea passage sought it of Tyrrhenian pirates (Greeks called "Tyrrhenian pirates" those who called themselves "Etruscan merchants"). As they sailed, the Tyrrhenians began to feel that their passenger was too spooky and should be disposed of, overboard. Dionysos, being divine, knew their thoughts and, by his power, transformed the mast into a living grapevine, seeing which the Tyrrhenian pirates, in insane fear, themselves jumped overboard; Dionysos kindly turned them into dolphins, leaned back, and continued his voyage. It is a Just-So Story: Why the Dolphin Follows Ships at Sea. As with so many of Exekias's pictures, this is a rare subject in Greek art, and no other version is so fine as this. There is nothing superfluous, but the whole story is here, yet it is also a masterpiece of pure design, a perfect composition in a circular frame, with both the vine and the dolphins nearly enough symmetrical to fulfill decorative requirements but freely enough disposed to seem alive.

[MA 89]

Since Greek art is ancestral to all the basic assumptions of western

art, we easily forget that in the two and a half millennia (five times as long ago as the Renaissance)

since it was made wars, greed, religious objections to the subject matter of

Greek religion, and ordinary deterioration of materials all have taken their

toll. We have only bits of late

Greek books. We have hardly any Greek

painting, though we know how famous it was. We have an even tinier fraction of all the Greek bronzes

that once existed (both statues and vessels) than we have of the original stone

statues. The griffin heads gave us

a glimpse of Orientalizing metalwork.

Even books of the Roman Empire period mention Archaic bronzes, as well

as later ones, with admiration.

Occasionally one is found, almost always in a rich burial of some

foreign people, for example the Thracians who lived in what is now

Bulgaria. The great Vix Krater, today the principal

treasure of the Archaeological Museum at Châtillon-sur-Seine, comes from the tomb of a Celtic princess or priestess

of the Hallstatt A period; she was buried, judging from the latest objects

buried with her, shortly before 500 B.C.; the krater is hard to date exactly,

but it is much closer to 550 B.C.

It is five feet tall and five feet in diameter, a masterpiece of

extraordinary value from one of the famous bronze-working centers, such as

Corinth or Laconia (Sparta), and it is not surprising that it should have taken

a couple of generations to travel all the way to northern France. It may have belonged first to

Etruscans; it may have been traded at Marseille (a Greek colony, Massilia) and

travelled up the Rhône river system; it may have been enjoyed as a prized

object by the Celts before it became funerary wealth. Why do we not find such things in Greek tombs? The Greeks regarded death differently

and did not stuff tombs with worldly goods.

[A 44]

There are inscriptions by some of the figures on the east and north

friezes of the Siphnian Treasury and even a signature, unfortunately too

fragmentary to be sure of, but it points to one of the Cycladic sculptors who

are also known from signatures to have worked in Athens in this period, when

there is much more Island influence than before in Athenian sculpture. Siphnos did not have its own school of

sculptors, much less a major artist like this one. In the details that we are studying we have part of the Battle of Gods and Giants (in Greek

myths, a more primitive, earth-born race of divinities), Dionysos at left, then

Kybele, the great goddess of Asia Minor with her lion chariot--one lion biting

the buttocks of a giant who turns his head so we see his helmet frontally, then

striding in step the twins, Apollo and Artemis, and a fleeing giant. The bodies are massive and bulky,

reminding us of the approximately contemporary Anavysos Kouros. Even though we must emphasize again

that a relief sculpture is a carved picture, so that the artist can do any

kind of pose or effect that he could do in drawing on a vase, still this is

extremely bold and innovative work, with its wind-blown drapery, twisting

figures, convincing renderings of the dead and dying (appealing to the artist

not for their gore but for the challenge that they afford), and elaborate but

clearly thought out composition.

The drapery of the seated assembly

of the Olympian gods on the east frieze takes the drapery that Exekias used

on Tyndareus on the Vatican Amphora one step further; it is not more than a

decade later. Notice how Ares

turns his upper body in three-quarter view. But there is something more. When we turn back to Athenian Late Archaic art, we shall see

a new vase-painting technique, which reverses

black-figure; now the background will

be black, and the figures the reddish colors of the clay. In architecture until now Greeks had

colored the figures and left the background pale, following the example of

Egyptian reliefs, but in the friezes of the Siphnian Treasury you can clearly

see, especially in the crevices around the figures, the remains of dark paint,

and the figures were pale (marble) with only facial features, hair, and border

patterns in color; in other words, the relief figures here are painted like kouroi and korai. Art historians

are convinced that there is a real connection between the change to a

dark background in the frieze of the Siphnian Treasury and the change to the

new red-figure (black background) technique in Athens only a couple of years

later, at most. The change to

red-figure vase-painting is a hallmark of the Late Archaic period.

[O 408] [O 406] Iran (±50°E.) seems a long way from Greece (±22°E.), but the

Achaemenid Persian Empire already

extended from Asia Minor (and had terminated Egypt's Saitic Revival of Dynasty

XXVI in 525 B.C.) to modern Pakistan and some of northern India and, when

peninsular Greece showed concern for the Ionian cities that had been swallowed

up, Darius I, the Great, was convinced that Greece could not be let be. Not that the Persians were heavy-handed

overlords; the Hebrews greatly preferred them to Babylon; ordinarily they set

up a satrap (a local dynast, what we

would call a puppet government) to maintain order and collect taxes. Remarkably, the tiny Greek city states

stood up against the Persians, even managed to cooperate with each other to an

unusual extent and, not without great cost, eventually kept their

independence. Given the Persians'

logistical difficulties fighting overseas (none of our large transports!),

their eventual defeat was not due to Greek valor alone, but the Greeks did

defend themselves valorously; they never forgot it. Did the Hebrews ever forget that David overcame Goliath?

[O 405]

A relief from the Treasury at

Persepolis shows the king enthroned like a divinity, with incense burners

in front of him, approached by a foreign ambassador who holds his hand before

his mouth even as Hammurabi did before the god Shamash, in the Old Babylonian

18th century B.C. This ambassador

wears the sleeved and trousered garments of a central Asian, but the king and

his bodyguards wear loose draped clothes, and in these we see the first pleated

drapery in Middle Eastern art. It

is a regimented, formulaic version of Archaic Greek drapery at exactly the

phase that we have just studied in the Siphnian Treasury at Delphi; in the

latter, no two drapes are alike; here all are done identically--any hint of

personal individuality in any of the figures is rigorously excluded. Also, in Greece, within another 15

years, the drapery had evolved much further, whereas here in Persia, once they

had imported sculptors create a style for them, it was maintained unchanged

until Alexander the Great conquered the Persian Empire in 330 B.C. Perhaps when you get a style readymade

and not out of your own tradition (which in the case of the Persians was more

like Scythian art than like this) you are not equipped to make it evolve; you

can only clone it. The remarkable

thing here at Persepolis is that a small army of foreign artists was caused to

create a brand-new architecture which, while using what they knew from their

homelands, is definitely a unified, Persian style.

[O 414]

Nowhere is that seen more clearly than in the capitals in the form of addorsed bulls (as here) or lions. This is a brand-new type of bracket

capital; the primary ceiling beams fit between the backs of the bulls' heads,

the secondary beams lie at right angle on

the bulls' heads between the horns, and the forelegs are tucked under squarely

to adapt the animal foreparts to their architectural function. Between the animals and the fluted

shaft are volutes, recognizably similar to those of Archaic Ionic capitals

(which at Ephesus had rosettes in the center of the volutes) but used

vertically instead of lying across the echinus horizontally.

[O 415]

Greek artisans were always skillful in adapting their styles to the

taste of foreigners, not least the Persians, even in the later years of the

Persian Empire when Greek art was Late Classical. The wingèd ibex is a

handle from a silver vessel; the ibex is an animal that goes back all the

way to Late Neolithic (the Susa A beakers) in southern Iran, and here it is

designed in accord with the decorative preferences of the Persians, except that

the naturalistic wings are purely Greek, and the little plaque below the hind

legs is a Late Classical mask of a Greek satyr. This piece is not "possibly" but patently

Greek workmanship; they also made wonderful pieces with Thracian or Scythian

subject matter to the taste of those peoples. Why "compromise" their own style? Greece is not wealthy in natural

resources, only in skills; also, her neighbors craved these products.

[A 27] Kore #674, on the other hand, has a

very marked personality. This is

the work of an Athenian sculptor of about 510 B.C. It is almost lifesize and preserves nearly as much paint as

the Chios Kore, #675, including the paint on her eyebrows and eyes. Even though we have no reason to think

that the korai are really accurate

portraits, what is important is that beginning with the Peplos Kore the best

ones are strong, individual characterizations, meaning, if nothing else, that

the parents of daughters took them seriously as individual persons and wanted

them represented in full personhood in the statues they dedicated--not just as pretty female

horseflesh. We have not seen such

individuality in votive statues in any previous art. The sense of quiet inwardness in Kore #674 is really remarkable. The sculptor has given her more delicate

facial structure, smaller, more sloping shoulders, half-closed eyes, and a

sober mouth that looks as if it might speak. The Archaic smile and the robust and bouncy forms that went

with it were beginning to go out of fashion.

[A 12]

In June, 1959, in the course of road work in Piraeus, the port city of Athens, men came upon a warehouse that

had burned down early in the first century B.C., perhaps in the time of Sulla,

when a lot of Greek art was being transported to Rome. The fire was the reason for four major

bronze statues remaining buried there and thus being saved from the

vicissitudes of history. The other

three date from the Late Classical period, but the fourth is this Late Archaic bronze kouros. Since he is not only over lifesize but

held a bow (probably) in his left hand, this should be an example of the kouros type serving for the statue of a

youthful god: Apollo. Prof.

Caroline Howard, indeed, believes that all four of the Piraeus bronzes were

booty from the sacred island of Delos in the Cyclades, one of the principal

sanctuaries of Apollo and Artemis, who, according to the myth, were born

there. Because we have no other

large bronze kouroi to compare, we

can only say that based on the pelvic area the Piraeus Kouros must be a little

later than the Anavysos Kouros, perhaps ca. 520-510 B.C. It certainly is work by a major artist,

and its discovery came as a great surprise. The freedom with which the artist treats the arms and hands

is due to its being bronze, hollow cast, by the same lost-wax method that we

studied in the Dynasty of Akkad.

It was what we call a direct casting; when it was found, the clay core

and the oxidized metal armature were still inside it. It now is exhibited in the Piraeus Museum.

[MA 65] shows two sides of the very fine base of a lifesize kouros statue (cuttings for feet in kouros position can be seen on the top of the block); the third

sculptured side (back is blank) shows youths pitting a leashed dog against a cat. Since it was found near the Dipylon,

the kouros probably was a grave

statue--of a youth of eminent family, when even the base is so fine and

elaborate as this. The figures of athletes are less than a foot tall, no

larger than the figures on a large vase; the background is painted red, the

figures left pale, so they stand out like figures done in the red-figure

technique, especially resembling the athletes on a calyx krater by Euphronios

in Berlin. The artist is very

interested in details of musculature and experiments with showing how the rectus abdominis muscle (which he renders in a way that reminds us of a

muffin tin) responds to twisting in the torso. Euphronios's work coincides with the adolescence of a future

general, Leagros, who was a strategos

at the Battle of Marathon in 490 B.C.; in the decade ca. 510-500, he was the

most popular youth in Athens, praised, with the vase-inscription "Leagros kalos" by the principal vase-painters, by Euphronios most of

all--thus the dating, ca. 510 B.C., for the reliefs on the statue base.

[MA 86] Of the two most wonderful vase-painters

whose best work was done during Leagros's youth, Euphronios specialized in cups and kraters, Euthymides in amphoras

and related shapes. Euphronios's calyx krater, once in the Metropolitan

Museum, NYC, made by the potter Euxitheos,

is famous not only for its beauty and interesting subject matter but because in

1972 a million dollars was an unprecedented price for a Greek vase. This calyx krater is still broad in

proportion to its height, not very different from the first one by Exekias some

twenty years earlier; it is a vase-shape that gives the artist an unbroken

field to draw on. The subject of

the main picture is the piteousness of the death of the very young hero, Sarpedon--beardless and long-haired, he

has only "peach fuzz" on his cheeks--raised to poetic tragedy by

showing Hypnos (sleep) and Thanatos (death) in the form of wingèd

men bearing his limp and bleeding body from the field of battle. Hermes, the god who guides souls to the

underworld, superintends this epic EMS.

Notice what Euphronios can do with the new technique, drawing with a

brush instead of incising the lines; he can dilute the glaze-paint for a pale

brown subordinate line or use it very thick for a strong contour line, and he

can vary the thickness of the line. Notice also the difference that red-figure makes in the

drawing of the floral chains above and below the picture. Finally, notice that this large punch

bowl (kraters were for mixing wine with water at a symposium) has very

adequate, well designed, sturdy handles.

[MA 22]

One of Euthymides' two famous

amphoras in Munich will serve as an

example for Euphronios's equally great contemporary (also, compare his drapery

with that on Kore #674). They seem

to have been friendly rivals; alongside one vase-picture Euthymides wrote,

"Thus never Euphronios".

There is some evidence that they both hobnobbed with the upper

class. Perhaps both of them, but

certainly Euthymides, who signs his name, "son of Polios", in the

formula that free-born citizens used, was an Athenian citizen; some of the

artists and artisans were metoikoi

(dwellers-with-us, i.e., resident aliens), and some were slaves or freed

slaves. These observations add

nothing to his work, which would be just as great in any case, but they are

significant for the social standing of artists in Late Archaic Athens. Theseus,

Athens' own hero, like the other Greek heroes, figures in stories where a bride

is abducted (Athenian men did not

abduct their wives; these stories are understood as occurring in a legendary

past: the bronze age); here he carries off Korone. Euthymides is more selective as to

which muscles he will draw in detail and which only imply; he is more concerned

with the powerful contour (as of Theseus's leg) and with drapery swinging with

the action of the figures; his gestures are more emphatic. That is just his personality. Note that this amphora is a direct

descendant of Exekias's, only it is not so fat; on this vase-shape, in this

generation, it is not unusual to do part of the border patterns in

black-figure.

|

| With color digital photos, this cup is the subject of my January post in Opera Nobilia |

[MA 23]

The Berlin Painter was

Euthymides' pupil but is as different an artistic personality as he could possibly be. He is the last vase-painter to decorate the Exekian Type A

amphora, and even he abandons the frame around the picture. After all, in red-figure, the picture

is no longer a pale "window" on a black pot; the ground is also black

behind the figures, so the Berlin Painter took the step of simply spotlighting

his red figures on the black field.

This decision entailed very thoughtful grouping, as you see on the Berlin Amphora, from which he takes his

name, since we have no signature.

Here there is no story, just the exquisite contrast between the satyr (Nature Boy) and the urbanely

elegant deity, Hermes; one clothed,

the other nude, one with a horse's tail and ears, the other with his wingèd

helmet, both equally slender and long-legged, with their arms and implements

reaching out to animate the solid black field. The final characteristic touch is the fawn; it is a woodland

creature, so it belongs with the satyr, but its real function in the design is

to separate the legs of the two anthropomorphic males (which otherwise,

visually, would be tangled) and in a gesture typical of the species to point up

with its head to Hermes' hand holding his kerykeion

(caduceus) and a kantharos [MA 74,

row 4, right]. It is so artful and

so natural, all at once.

[MA 28]

Our last Late Archaic red-figure vase-painter actually worked mostly in

the next period, after the end of the Persian Wars; the give-away in his

drawing is the wavy lines in the drapery and the proportions of the faces

(there are other such date-indicators elsewhere in his work). The Brygos Painter's Louvre kylix dates from the 480s, the Berlin

Painter's amphora from about 490, but the Pan

Painter's Boston bell krater with the Death of Aktaion on one side (and the god Pan chasing a young

goatherd on the other: we take his name from the picture of Pan) should not be

labelled "first quarter, V century B.C.". It could perhaps

date from ca. 475, but that's not the same thing. If you take the senior course in Greek art, we shall see

whom the Pan Painter actually apprenticed with, but here we need only observe

that he admired the Berlin Painter and tried to maintain into the second quarter of the 5th century the

emphasis on elegant design that the Berlin Painter epitomized. We call such an artist, who works in

the manner of pre-existing art rather than basing his style on primary experience,

a Mannerist, and seeing Mannerism

emerge at this point in Greek art is yet another indicator of the art's

self-awareness, as Art. The

picture of Artemis slaying Aktaion is a perfect example of the Pan Painter's

Mannerism: the V-shaped composition, the reaching out of limbs and three

C-shaped doggy tails to animate the black field, the ballet-dancer poses of the

angry goddess and the doomed hunter.

For the story, as such, is

primitive and gory; the hapless Aktaion happens to see the fiercely virginal

huntress goddess bathing in a pool, and she not only turns her arrows on him

but maddens his own hunting dogs, so they attack him as they would prey.

[B 1]

The Pan Painter's clinging to Late Archaic design is understandable in a

period when, as we know from literary sources and can see in the impact on most

vase-painters, Greek painting began seriously to address the illusion of

optical reality: showing light and dark with shading, abandoning the single

ground line to try to show figures and things in deeper space, seeking ways of

showing, for example, fish in water, figures in mist, the flash of light on

metal, the frothing at the mouth of an exhausted horse at the end of a

battle. Alas, that we have not one

of those paintings. Such effects

are impossible in red-figure, and the impact of such experimentation on

vase-painting was deleterious to the design

of the vase; now they sometimes forgot that pictures on vases are decoration as

well as pictures. Nor can their

occasional efforts to imitate painting in full color really give us an idea of

what the famous lost paintings were like.

Recently at the Greek colony of Paestum

south of Naples, Italy, archaeologists discovered a tomb with full-color paintings of about the same date as the Pan

Painter's bell krater. On the ceiling

is a remarkable picture of a man diving into

a pond from a built diving platform, with a couple of spindly trees to show

that it is outdoors; on the wall is a banquet scene. This is the same kind of subject matter as we find in

Etruscan tombs of the same date (so silly people can no longer pontificate

about how only the Etruscans give us

proto-landscape or how curious it is

that the Etruscans, "unlike the Greeks" show funeral banquets in

their tombs, as the Egyptians did; in fact, tomb paintings from Lycia, neither

Greek nor Etruscan, in southwest Asia Minor of the Late Archaic period also

have the funeral banquets). Of

course, Paestum is a western colony, and we have already seen that their

Archaic temple is significantly different from one in the Greek peninsula,

Corinth. But, in any case, tomb paintings, whether Greek colonial

or Etruscan or Lycian, give us no more idea of the famous innovative

breakthrough paintings described in literary sources than vase-paintings do,

and rather less than the few vase-paintings that (ill advisedly, so far as the

decorative effect is concerned) actually try to imitate a full-color painting.

|

| (author's photo, 1959) |

[MA 70, left] We did not study Etruscan Orientalizing, although their

jewelry and other metalwork closely parallel Greek Orientalizing; their

cinerary urns are very much their own.

Not since Samarra Neolithic of the sixth millennium B.C. have we studied

a vase that literally expresses the metaphor of the human body as a

vessel. The Etruscans of Dolciano practiced cremation; a cinerary

urn is for the ashes of the

deceased: notice that the handles

attach to the shoulder of the pot,

where, on the front, there are nubs for nipples; the neck of the pot = the human neck and supports a schematic

"portrait" of the deceased.

To complete the metaphor, the urn is set in a throne of the shape that

was a seat of honor among the early Etruscans. These urns are certainly interesting, but, to tell the

truth, they have very little to do with Etruscan art of their century of

greatest wealth and power, the sixth century, when Etruscan kings ruled Rome

and when the impact of Greek art, acquired by trade, on their own art was

pervasive.

[B 2]

It even extends to the subject matter. No story could be more particularly Greek than that of

Achilles lying in ambush to kill young Troilos so that Troy might be

taken. We saw it on the François

Vase in the 560s; here it is in the third quarter of the sixth century on the

wall of a tomb at Tarquinia, one of

the most important Etruscan artistic centers (see [MAP 3], where

"Corneto", the formerly used Italian name for the town, marks the

site of Tarquinia). The tomb is

called the "Tomb of the Bulls"

for one of its other motifs. This

is Etruscan Archaic art contemporary with Exekias, but the Etruscan artist,

although he uses the same composition for the Troilos story as we see on

numerous Greek vases, is much more prone to fill up all the "extra"

space with plant life. Also he is

blithely unconcerned about bodily proportions of either men or horses but

emphasizes expressive gestures, so that the scene is vivid. Furthermore, these tombs are chambers

the size of a room in a house and indeed are made to resemble house architecture,

and they are covered by large tumuli. Even the Tomb of the Diver at Paestum

is not like these, while in Athens and Corinth and the Cyclades funerary

customs were radically different.

For the Athenians, a stele or a statue was a monument to the departed (as the inscription on the Anavysoskouros makes clear). For the Etruscans, the cemetery was

literally the city of the dead, the tomb chambers dwellings, and the paintings

on their walls (apart from a few like this one of Troilos and Achilles) representations

of a good life in the beyond. As

we observed earlier, it is the Greek belief that is untypical and so, also,

their funerary art, which is concerned with loss and memory rather than with

rewards and punishment or a magical promise of everlasting banquets and sports.

[MB 27], a view into the Late Archaic "Tomb of the Lionesses" at Tarquinia

illustrates those points. The

ceiling is painted to show the ridge pole of a house and there are Tuscan

(=Etruscan) Doric columns at the corners; men recline at banquet on the walls

at left and right; on the end wall dancers at a banquet flank servants on

either side of a huge volute krater, which looks as if it is

silver-plated. Until the Vix

Krater was found, we might not have believed that a real krater could be so

large. Above the krater we see the

lionesses that supply a name for this tomb. A detail of the confronted male and female dancers shows the

same vitality, combined with disregard for proportions or articulations as the

earlier picture of Troilos. Note

that the ancient "color code", red-brown for males, is observed. We are not certain of the significance

of the dolphins leaping over the sea on the lower wall, although it is easy to imagine

that they might betoken passage to a world beyond.

|

| (There is another one in the Louvre, which now has benefited from cleaning) |

[A 325, (B)] Etruscan master bronzes survive as infrequently as Greek

ones, but one of the most famous of all ancient bronze sculptures, the Capitoline She-Wolf, is probably

Etruscan work of the last years of Etruscan rule in Rome, though we have no way

of ascertaining that the artist had an Etruscan rather than a Latin (or even a

Greek) name; the eyes, however, are executed similarly to those on some bronzes

that are certainly Etruscan.

Although the babies now nursing from the wolf are Renaissance work, the

familiar story, the foundation legend of Rome, the she-wolf nourishing the

abandoned babies, Romulus and Remus, and her full teats make them appropriate,

except that their Renaissance style

would go better with the Classical Arezzo Chimaera, illustrated on the same

Print, than with the Late Archaic She-Wolf. The Wolf is a technical and artistic masterpiece, better

than merely realistic, embodying the very character of the powerful animal

protecting the future founders of Rome as fiercely as she would her own

whelps. She has never been lost or

buried but has been on exhibit in Rome ever

since she was made. Roman

coins show this or a similar she-wolf nursing the babies, and knowledge of

these coins guided Antonio Pollaiuolo in making the replacement babies.

[MA 49]

The other towering masterpiece of Etruscan Late Archaic is the group of