|

| See below [A362] for the relationship of this funerary stele to the sculptor Agorakritos, a close disciple of Pheidias. |

Synopsis of the works shown for this unit:

By 454 B.C.,

when the treasury of the Delian League was transferred to Athens, Pericles was

securely in power in Athens. The

Persians (their "evil empire") were no longer a threat and, in

control of the Delian League, Athens had a virtual empire herself. All the contributing states paid to

protect the Aegean world from the Persians; Athens maintained the requisite

fleet of warships. The Acropolis

of Athens a generation after 480 was still in ruins. Athens now could take advantage of another provision of the

Delian League, the restoration of sanctuaries devastated by the Persians. In the sixth century the sons of

Peisistratos had begun a temple for Athena Parthenos that would have been as

large as the Parthenon that Pericles now built (it was destroyed by the

Persians before it was finished).

Technically, what Pericles now undertook was perfectly legitimate, but

it certainly could not have been done without exceptional funds belonging to

the League. For an ancient

economy, an undertaking like the building program on the Acropolis required a

larger fraction of total wealth than the fraction of ours that NASA and NATO

together require. Only the

Parthenon and the Propylaea were built before first the Peloponnesian War (the

other side led by Sparta) broke out and then, in 429, Athens was decimated by

the Plague (we do not know whether it was Bubonic or some other), in which

Pericles himself died. During

breaks in hostilities the Temple of Athena Nike (in the 420s) and the

Erechtheum (beginning in 421 but not finished until the end of the century)

were built. Socrates taught during

this period as well as a number of Sophist philosophers drawn to Athens under

Pericles. Sophocles' plays are of

this date. The writers who belong

to the period of the Athena Nike temple and the Erechtheum are Euripides and

the author of political comedies, Aristophanes (he had a lot to write about);

towards the end of the century, we perceive a change in the sensibility of the

society both in the literature and the visual arts, as Athens loses her

short-lived political leadership in the Greek world. Our written sources continue to bear witness to remarkable

developments in Greek painting, all lost.

What is clear, and very important, is the emergence of artists as

star-quality personalities and as theorists rather than only artisans (another

very "modern" first from Greek culture). One source tells us of a scene painter (making scenes for

the theater backdrop) who made the lines come together at a point to give the

impression of regularly receding distance: it sounds like perspective. Ictinus, one of the architects of the

Parthenon, wrote a treatise on its design. Pheidias not only was placed in charge of Pericles'

undertakings, and made the chryselephantine

Athena Parthenos, but also seems to have been an intimate friend of

Pericles. These developments were

not confined to Athens. The

sculptor Polyclitus, who worked in Argos in the northern Peloponnesos, wrote a

treatise on his canon of human proportions. Like the ratios in the Parthenon, his seem to be related to

the geometry and number theory of Pythagoras of Samos. The artist as philosopher is a novelty

indeed. In this connection, it is

worthwhile to take note of the Athenian attitudes about the individual in his

society, reflected not only in the funeral oration by Pericles (just before his

own death, recorded in the historian Thucydides) and in the frieze around the

cella of the Parthenon but in the beautiful grave stelae which Athenians set up

on family plots in the Kerameikos cemetery near the Dipylon Gate in the late

fifth and fourth centuries B.C.

Selected works from the University Prints for this period

Kresilas's

portrait of Perikles, illustrated for comparison with the portrait of Themistokles at the end of the preceding post (its authorship is well attested to, but we know practically nothing else of

Kresilas), may have been made in his lifetime or when he died in 429 B.C. Like Themistokles' and Anakreon's, it

was a full-length portrait, but we have only several bust-length copies, of

which the one in the British Museum is not only the most attractive and least

restored but, having never been broken at the neck, guarantees that the

inscription, PERIKLES, really belongs to this facial type; it also shows the

tilt of the head, which lends the portrait individual character. Notice, too, how the helmet, pressing

on the thick curls behind the ears, forces the shell of the ear down and out. This portrait suggests not only a

powerful leader but an inner person, though there is little specific about it;

it is perfectly consistent with the character of the astonishing art of the Age

of Perikles. It suggests what

intricate and subtle meaning being Athenian and being Greek had for them at

this time; we get the same impression from reading Thucydides.

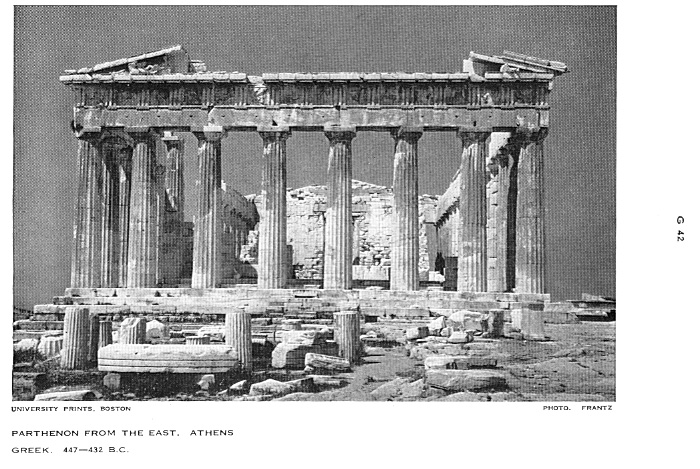

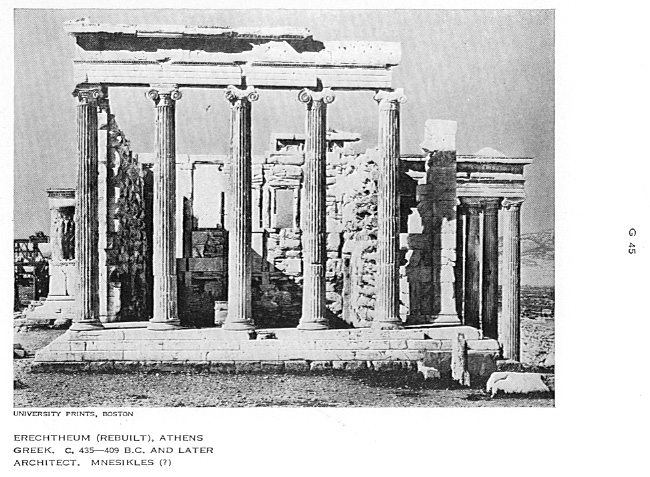

[G 40] [G 38] It is hard to imagine what the Acropolis looked like during the generation between the Persian Sack and the Periklean building of the Parthenon and Propylaia; we know that the Peisistratid Parthenon was never completed, and much of the marble quarried for it was used in the Themistoklean Wall, built to protect Athens in the Persian emergency. The Old Athena Temple, in the middle of the Acropolis, must have remained standing in part, however damaged (labelled "Hekatompedon" on [G 40]); it would be torn down before the Erechtheion was built, beginning in 421. The Periklean Parthenon, or Temple of Athena Parthenos, the Virgin, was begun in 448/7. The principal architect was Iktinos, who wrote a treatise on his design of the temple and its proportions, evidence that he thought of himself as a "philosopher" rather than merely an artisan. Ancient artisans were not also authors. He was assisted by Kallikrates, who may have been a specialist in Ionic design. For the Parthenon, the most famous Doric temple, is not typically and not entirely Doric; in particular, (1) the second, west cella had tall Ionic columns instead of double-decker Doric, as in the main cella; (2) the continuous frieze around the top of the cella wall and across both porches is Ionic; (3) the porches at both ends of the cella are not with Doric columns in antis, but Doric prostyle, which is like the plan of porches of the great Ionic temples at Ephesos and Samos, as well as the Nike Temple and the Erechtheion here (see [G 69]). It also is unusually large; the column diameters are comparable with those of the Temple of Zeus at Olympia, but the façade is eight columns across (with the flank columns, as usual, twice times plus one, so seventeen). The Parthenon, besides, is designed in terms of interrelated ratios, 4:9 being the proportion of total length to total width and of all the larger and smaller proportions throughout the building, instead of in terms of simple 1:2, like the Zeus Temple at Olympia. Athens has its own mountain of beautiful marble, Mount Pentele, and the Parthenon, Propylaia, Nike Temple, and Erechtheion all are built entirely of marble (except for some decorative use of Eleusinian gray limestone on the Propylaia and Erechtheion). Greek temples were built colonnades first, then cella and roof, finally the pedimental sculptures, which aren't structural. The building payment records are partially preserved, and we know that the metopes were complete by 442 B.C.; the temple was dedicated in 438 B.C., which means that Pheidias's chryselephantine (gold and ivory) statue of Athena in the main cella, 40' tall, was finished by then--and, of course, the roof over it; [MG 156] shows an old reconstruction model; there is a better one now in the Canadian Royal Ontario Museum. The reconstruction of the statue is based on reduced-scale freehand copies and descriptions, since it was impossible to make pointed copies of a work such as this. Payment records for the pediment sculptures continue from 438 to 432 B.C.; then the Parthenon, at least, was complete and then, too, the war with Sparta and her allies, the Peloponnesian War, began. The architect Mnesikles designed the new gateway to the Acropolis, the Propylaia, replacing the sixth-century Archaic Propylaia, and construction began in 437 B.C. This building was not finished when war broke out; it was never to be finished, although its appearance was entirely satisfactory, at least in the eyes of later architects; see [G 39] for its western aspect, a drawing showing what the Acropolis would have looked like as you approached the Propylaia, with the huge Parthenon on the highest part of the rock towering over everything else. The inner, east façade of the Propylaia stood on higher ground than the outer, west façade; in the passageway, to reach the higher roof of the inner part, Mnesikles availed himself again of the slenderer Ionic column. In the Parthenon and Propylaia the seminal idea of using a second, fancier or more delicate, Order for the interior of a building is first established. It is possible that Athens' interest in the architectural Order of the eastern Greeks was connected with their being her allies, states that paid tribute to a virtual Athenian empire, monies in return for the protection of the Athenian navy, lest the Persians return. Owing to a clause that allowed these funds to be used to restore sanctuaries destroyed by the Persians, they also helped to pay for these very expensive buildings. The Life of Perikles in Plutarch's Lives of the Noble Grecians and Romans (the title in John Dryden's translation from the original Greek) is not unbiased or wholly trustworthy, but you will find it enlightening and interesting reading; it gives a vivid idea of the intellectual and artistic life of Periklean Athens. The Nike temple, built in the 420's (its parapet, visible in [G 39], added about 410), and the Erechtheion, begun with the temporary Peace of Nikias in 421, interrupted by the debacle of the Syracusan expedition in 415, and completed between 409 and 406, both are entirely in the Ionic Order. In fact, they establish the Athenian version of the Ionic Order which differs from that of the Greek east, in Ionia itself, in some details. [G 70], your Print showing the three Greek Orders, actually shows the Ionic of the Athenian Erechtheion, not the Ionic of Ionia. The name of the architect of the Nike Temple and the Erechtheion is not given in the literary sources, but arguably they might have been designed by Kallikrates; a good case has been made for that attribution. Both [G 39] and the plans drawn to scale on [G 69] show how small and delicate the Nike Temple and the Erechtheion are in comparison with the Parthenon, and [G 69] shows how much more elaborate the plan of the Parthenon is than that of the Zeus Temple at Olympia.

[A 161]

It is mostly as a consequence of its use as a church, of the Virgin Mary

instead of the Virgin Athena, in the Greek Middle Ages (Byzantine Athens) that

only the metope sculpture on the south flank of the temple is well

preserved. This was because the

south side was walled off, so these particular pagan subjects were of no

concern to the church. As you can

see in the general view, the relief sculptures on almost all the rest were

deliberately chiseled off. With

mixed motives, but partly fearing that the Turks, whose religion abhorred

images, would consign even more marble sculptures to the lime kilns (Greece

would shortly be free, but was still under Turkish rule), Lord Elgin had the

south metopes and much of the frieze and pedimental sculptures transported to

the British Museum, then a new institution. There they remain, a bone of contention ever since Greek

Independence was attained. The

south metopes show Greeks fighting with centaurs, not the Wedding of Perithoos

but single combats, almost emblematic of the struggle between humanity and

bestiality, which the Greeks were fully aware was a battle fought within

us. Each is an original

composition, and it is possible to sort out several different sculptors' hands

among the surviving metopes, though they are also sufficiently alike in scale

and spirit to work together rhythmically as part of the same architectural

decoration. We are told that the

sculptor Pheidias, who was a personal friend of Perikles, was the overseer of

the entire Acropolis project, and unquestionably there is a very great artistic

mind and will behind all this work, however little of it (if any

while he was mainly concerned with the Parthenos statue) he may actually have

executed. Comparing these metopes

with those from Olympia with the Labors of Herakles a generation earlier, we

see not only higher relief and livelier and more varied compositions but a wholly

new attitude. It is very difficult

to describe it adequately, but the Parthenon sculpture makes us feel very

strongly that it is really "about" much more than the subjects that

it so wonderfully represents, that it is about what it means to be human, and

we are astonished that carved stone has been able to impress itself so strongly

on the imaginations of generations of different people in this way,

irrespective of their own ethnic traditions. Asian visitors to Athens or to the British Museum perceive

it just as Westerners do, and just as we appreciate Asian classic art, once we

study it. H. W. Janson in his History of Art says of the

pedimental sculptures, "There is neither violence nor pathos in them,

indeed no specific action of any kind, only a

deeply felt poetry of being".

In this context, such abstract-seeming language is not "mere

words"; he is talking about transcending naturalism as such, making poiesis out of mimesis, as we said above in discussing the Bologna-Dresden Athena

(the word "poetry" comes from Greek poiesis). When the

Romans called this art "Classic", the Latin word only meant that it

was top-notch, but since the late 18th or 19th century in the art historical

and critical literature pertaining to this art and High Renaissance art, it has

come to connote the qualities that we have been trying to describe. The metopes are already Classical in

this fuller sense, but it applies a fortiori to the great Panathenaic frieze

around the whole cella and to the pedimental sculptures.

[G 42]

We have been looking at the east frieze; as this view of the east front of the Parthenon shows, the

front of the temple is much less well preserved than the rear; on the spot, we

can only see where the six prostyle

columns of the east porch stood.

The cella had been gutted long before, but some of the worst damage

occurred in 1687, when the Acropolis was under siege. The Turks had their gunpowder magazine in the cella of the

Parthenon, and the temple was blown up when a Venetian cannonball hit it. The Greek Archaeological Service cares

devotedly and skillfully for the temples on the Acropolis; since World War II,

they have re-erected the columns on the north side that had lain in rows of

(chipped) drums on the ground since they were blown out in 1687. The east front is, however, well enough

preserved that we get a good sense of the grace and majesty of the temple front

as one stands in front of it, and in the corners, where part of the raking geison is preserved (with some of the sima, rain gutter, and a lion's head water spout at the north, or

right-hand, corner), casts of the reclining god and the horses (heads)

of the chariots of the Dawn and the (setting) Sun have been placed to show how

they fit in the pediment and how they look when viewed from the ground; these

originals are in the British Museum.

[A 136] [A 137] The east pediment represented the Birth of Athena with the other gods in attendance, the chariot of the Dawn rising in the south corner, the Sun's setting in the north corner; this is a new device for these tight corners, in which we are asked to imagine the horses disappearing behind the floor of the pediment, doubtless inspired by new illusionistic devices in Classical painting. The nicknames, "Fates" and "Theseus", that 19th-century Guidebooks gave these sculptures are not to be perpetuated. The three females are goddesses, and the young male god is either Dionysos or Herakles; the rock that supports his elbow is covered with an animal pelt as well as a cloth drape, and the animal is a large cat: Dionysos's panther or else Herakles' Nemean Lion skin. Herakles was a Hero, not a god, but he had an apotheosis when he died: he became as a god and dwelt among them. Either one of them would have been shown bearded in the Archaic period, and Dionysos would have been clothed, but in the Classical period the very idea of the gods changes. The Artemis in the east frieze is certainly not the image of a killer of Aktaion or a slayer of Niobids. In these pedimental sculptures more than in any others we see what Classical art is intent on and does. Mastery of the organic structure of the human body and of the behavior of draped cloth in relation to bodies by now is so perfect as to permit the sculptor to use the properties of the bodies and of drapery for purely poetic ends. He convinces the casual viewer that they look "perfectly natural", but the massive limbs and torsos of these three goddesses are larger and simpler than natural bodies, the easy seeming pose, with one goddess reclining in another's lap, would be awkward and unendurably uncomfortable in nature, and in the "realistic" drapery the sculptor has taken his profound and detailed knowledge of all the kinds of lines and folds and pockets that cloth over bodies can make, and he has made a great abstract formal art out of it, using hollows in bunched folds for interesting shadows, using stretched cloth to emphasize the thrusts and basic forms of the limbs, which in all three goddesses together make a rhythmic composition. And this great abstract formal art makes the sculptured figures become somehow the essence of divinity, and of humanity ideally considered. The Dionysos/Herakles is more than a representation of one particular god with a particular cult and myths. As mentioned above, even so skillful a writer as H. W. Janson could say nothing more concrete about this figure than "deeply felt poetry of being". Notice, too, considering it as a human nude, that it is not, certainly, devoid of sex, like an angel, but its nudity and its beauty transcend rather than deny all the everyday urges. This is indeed divine nudity, not a state of undress. The sculptor's mastery of anatomy permits him to lengthen the lower torso to give the figure a longer curve and a greater sense of ease without in any way distorting it.

[MA 76]

In the Lykaon Painter's Boston pelike (see [MA 74]), the University

Prints once again selects, to exemplify Classical red figure, a vase with a

picture probably derived from a panel or mural painting of this period painted

in full color and with some indication of terrain. Although such vase-paintings are not so attractive,

considered as vase decoration, as the compositions made up by the vase-painters

themselves with the whole shape of the vase in mind, it is most valuable in

showing how lost Classical painting, like the surviving sculpture, embodied the

new ethos in art, trying to suggest

what it is like to be a mere shade (Elpenor, at left) temporarily revitalized

by the hot blood of the two rams that Odysseus has sacrificed to call him up,

and what it means to Odysseus actually to speak with him; for this is a Nékyia, a calling up of the souls of the

dead (Odyssey, Book XI), and Hermes

as guide of souls supports Odysseus in this endeavor. Fifth-century Athenians, of course, did not think that you

could really call up the souls of the dead, but this is an illustration of

Homer's Odyssey, which the Classical

Greeks valued somewhat as we do the Hebrew Bible (the "Old

Testament"--not "old" to Jews!). The figures compare closely with the Parthenon frieze; the

vase was made about the time when the Parthenon was completed.

[MA 67]

One group of classical statuary that reached Rome without being shipwrecked en route represented the story of

the Niobids, as on the Niobid

Krater, but these date from the time of the Parthenon frieze or pediments. At least three Niobids, one in Rome [MA

67] and two in Copenhagen, belong to this group, which probably was a pedimental

group and possibly should be

associated with another pedimental group which was re-used in the pediment of a

Roman temple in the reign of Augustus.

We do not know where any of these sculptures came from, but it has been

argued rather persuasively that the style of carving is of the island of Paros,

an important school of marble sculpture, since Paros had perhaps the very

finest marble. Our Dying Niobid is a daughter in early

adolescence, falling to her knees as she tries to remove an arrow from her

back; her drapery falls off, giving the sculptor the opportunity to show her

still somewhat childish body and the poignancy of her unmerited painful

death. It is a masterpiece by an

unknown sculptor. The arrangement

of her hair and the "pool" of fallen drapery (which has the practical

advantage of strengthening the base of the sculpture) perhaps recommend dating

her in the 430's. In a pediment,

Apollo and Artemis, a little larger than mortals, would stand in the center,

shooting left and right; Niobids, smaller and taller, running, stumbling,

falling, fallen, and dead provide an ideal array for filling the low triangle

of a pediment. The Dying Niobid is

an reminder that, although in the third quarter of the fifth century Athens

attracted artists from all over the non-Dorian (not allied with Sparta) Greek

world, very important work was being done elsewhere, too--not necessarily on

Paros, even if the style is Parian,

for Parian sculptors travelled.

[A 362]

One Parian sculptor who travelled was Agorakritos, who is named as an associate and favorite pupil of

Pheidias; it may have been Agorakritos who carved the group of Poseidon,

Apollo, and Artemis on the east frieze of the Parthenon [A 157]. One of the most beautiful grave stelai

in the National Archaeological Museum in Athens is unmistakably closely related

to those gods on the east frieze, only just perceptibly later, so if the east

frieze is Agorakritan, so is the stele, his or from his workshop. Once the Parthenon was finished, there

were underemployed sculptors with unprecedented levels of skill and taste

available in Athens. The stele with the deceased youth holding up a

bird in a cage just above a cat (his pet) perched on a stele (his?) with a

small boy (brother or child slave?) disconsolately leaning against it far exceeds

the standard of quality of even the best grave stelai; it is to be dated ca.

430 B.C. The extremely refined

carving of the drapery and the restrained expression of grief and loss (of a

youth still concerned with pet animals, like the boys on the Late Archaic

Cat-and-Dog and Athletics statue base that we compared with Euphronios) are

remarkable. It reminds us once

again that the Greek concept of death was not a matter of rewards and

punishments or a life like this in the beyond; their monuments commemorate and

try to deal with the senselessness of a fine boy's dying when he had only begun

to live.

[G 50] [G 51] Mnesikles' wonderful design for the Propylaia was too complex, with several rooms and with the two façades at different levels, for refinements involving inward tilting and curvature, but its Doric Order otherwise is comparable with that of the Parthenon (and with the smaller temple, the Hephaisteion, on the hill overlooking the Agora of Athens). It also had to have an extra wide intercolumniation for the passage through the center; ruts worn in the rock going through the passage prove that chariots were driven through the Propylaia up onto the Acropolis, presumably in the Greek period. The lower gate that we see when we climb up to the Propylaia today is part of the Late Roman fortification (compare [G 39]), and the small amphiprostyle Ionic temple on the southwest bastion (never forget that the Acropolis is a citadel, which back in the Mycenaean age resembled Tiryns and Mycenae) is the Temple of Nike. The Propylaia itself is better appreciated today looking back at its east façade after we have reached the top of the Acropolis [G 51]. The questions associated with its unfinished parts need to be studied in the upper-division course in Greek art.

[G 52]

The Athenians had built purely

in the Ionic Order before the Temple of

Athena Nike (a stoa at Delphi and

another small temple down by the Ilissos River), besides using Ionic columns in

the Parthenon's west cella and in the passage of the Propylaia, but this is the

first Athenian Ionic temple in this course. Its plan is given on [G 69], a cella amphiprostyle fore and aft.

The undercut steps of the stereobate,

the lathe-turned column bases (and notice that the wall has a molding to

match), the column shafts with deeper flutings separated by fillets, the volute

capitals, of course, and the continuous frieze distinguish Ionic. The sculptures of the frieze have

suffered; the frieze on so small a temple is only about fourteen inches

tall. It had geisons and pediments and a roof, of course, but they are lost, and

the temple might be wholly lost but its blocks were built into the Late Roman

defensive wall hastily thrown up against the Germanic barbarians in the third

century A.D. A hundred years ago,

piece by piece, the Nike Temple was recovered from that fortification and

reconstructed on its own foundations, as you see. It is very gracefully proportioned and beautifully made,

even for Ionic; it dates from the 420's when we begin to see another of those

stylistic shifts in Athenian art, to a more delicate, less exalted style. It has been called "Post-Pheidian

Mannerism", it has been called "feminine", but let us merely

note that Athenian art in the last quarter of the fifth century, after the death

of Perikles, throughout the second part of the Peloponnesian War does differ from Periklean art and

shifts toward gracefulness.

[G 46] [G 45] [G 48] [G 49] [G 47] [A 166] Anyone visiting the Acropolis who feels overpowered by the Parthenon (as indeed we ought) may turn left (standing with one's back to the Propylaia) and regard a unique and lovely temple, the Erechtheion. From this vantage point, we see its back side, the only side without a porch of its own, where the architect, furthermore, had the most difficult task in harmonizing the differing levels and scales of the north and south porches (the small porch with caryatides, maidens, is the south porch), but it is here that we can best grasp what the architect has done. So far as housing cults was concerned, the Erechtheion (named for Erechtheus, the legendary king of Bronze Age Athens) would seem to have replaced the Old Athena Temple, which also had several cellas for several cults, but the new temple was built to the north, farther from the Parthenon, where the architect had to deal with the Acropolis rock's sloping away; either he had to do extensive extra-solid terracing under the foundations or find a creative solution to deal with the slope and multiple cellas at the same time. Consider how very conservative temple design is, and you will appreciate the audacious originality of his solution; there never had been and there never would be another Greek temple like this one. The Erechtheion has just been taken apart and reassembled (in the 1980's), the five caryatides that remain in Athens (Lord Elgin took one to the British Museum [A 166]) have been removed to the Acropolis Museum and replaced with very good casts, to save them from automobile exhaust, and the east façade once again is complete with six columns. Like the Nike Temple, the Erechtheion is pure Athenian Ionic (notice, for example, the wall base moldings that go with the lathe-turned column bases); the uses of maidens for columns is a standard option in Ionic, as we already saw in the Siphnian Treasury at Delphi. The Ionic palmette-and-lotus moldings at the top of the cella wall are most exquisitely carved. The frieze was made in an unusual way; instead of painting a dark blue background to set off the white marble reliefs, they brought grey limestone from Eleusis, twelve miles away, and made half-round white marble figures which were attached to the blue-grey frieze blocks with bronze pins, thus obtaining a dark background that could never fade or flake. You can see the pin holes on the frieze blocks, and in the museum a number of the half-round figures are exhibited pinned to new blocks of Eleusis limestone. The famous north porch is a full storey lower than the east façade, as you can see in [G 45]; here you see the Athenian Ionic columns that appear in most textbook diagrams. They are exceptionally elaborate, with guilloches on the upper torus of the Ionic bases and palmettes (similar to those at the top of the cella wall) for a necking around the top of each column shaft. If you look up into the porch, you can see how the coffered ceiling is made (these are only rarely preserved, so we almost forget that Greek temples even had ceilings!). The North Door [G 49] is probably the most influential door design in western architecture, especially after accurate architects' drawings of it were published in the 18th century, but before then there were doors designed resembling it owing to Roman architects' having used it and their doors having been published in drawings by Renaissance architects. It is all over Washington, D.C. The Erechtheion is entirely gutted, its interior arrangements even uncertain; the Turkish Pasha built his harem into it. Although today all six of the caryatides outdoors on the south porch are casts (subtly colored to blend with the ancient marble), we no longer have the ugly poles in between them. The old cast of the one in the British Museum (second from left in front) did not match so well. Since these statues have to look capable of doing the work of a column, they retain the massive proportions of the three goddesses from the east pediment of the Parthenon, but details of their drapery and the round faces betray their date, after 415 B.C. They need to be closely similar for reasons of architectural design, but they are not replicas; the sculptor worked out the drapery over the breast and falling over the bent leg differently on each. For his villa at Tivoli, the emperor Hadrian in the second century A.D. had copies of the caryatides of the Erechtheion made to stand along the edge of a long pool in its landscape architecture, but they were designed to bear an entablature and look incomplete standing by themselves.

[A 170]

The last fifth-century component of the Acropolis at Athens was the parapet around the Nike temple that we have already noticed in the reconstructed view

[G 39]. A great deal survives, on

view in the Acropolis Museum, but one slab is especially famous, by one of the

three best sculptors who worked on the parapet. It shows Nike, winged, adjusting her sandal (whether

she is fastening or unfastening it, and whether the gesture has special

iconographic significance, is difficult to decide). This relief is one of the finest examples of the fashion of

doing "wet drapery" at the end of the fifth century, although it had

begun a bit earlier. Like the

changes in kouroi in the Archaic

period, this fashion has at once a natural and a stylistic component. Its natural cause was the introduction

of silk culture (ultimately, all the way from China); fine silk, dampened by

perspiration and blown against the body, is more clinging than linen. Its stylistic component was as part of

the trend to a graceful, delicate, and sensuous style in the last quarter of

the century. It is a brilliant

development. The sculptor has all

the advantages of nudity in using the forms of the body as his composition and

all the advantages of drapery in providing rhythmic lines and shaded hollows

and interesting textures, and he has them together Compare her with the Parthenon frieze and pediments; they already have consummate virtuosity,

but the Nike adjusting her sandal some thirty years later uses virtuosity in a

different, daintier way, which one might characterize as lyrical.

[A 108]

The Louvre "Genetrix"

is one of many copies, full scale and statuettes (some of the statuettes of

terracotta), of one of the most popular images of Aphrodite in antiquity.

The original surely dated from the very end of the fifth century, and it

may be the type that the Romans used for the cult image of their Venus

Genetrix. The "wet

drapery" clings so closely that a person who worried about nudity might

protest, why bother? Yet the

purpose of its clinging is the same as in the Nike Parapet relief: the rather

Polykleitan pose and proportions and rhythm are clearly shown in the limbs and

torso, while the lines of the drapery across her body and thighs and the long

plumb lines of the unbroken folds framing her legs impart both stability and

grace to the composition. Only in

the fourth century will the Greeks for the first time represent Aphrodite

completely nude; it is funny how many people have a nude Aphrodite as their

stereotype of Greek art, and we have yet to see one. The Louvre statue has the whole right arm (lifting her

drapery) and the left forearm restored; their style is weak and

affected, but the pose and her holding an apple are correct, because several of

the small statuettes preserve these.

As a freestanding statue of a goddess, the "Venus Genetrix" is

not so slender and delicate; indeed, as you stand in the Louvre and look up

into her face, she seems veritably saucy-faced and wholesome; in this statue,

the sense of grace and lyrical feeling comes from the wonderful lines of the

drapery, so we hardly notice that the body is actually massive.

The Louvre "Genetrix" has recently been beautifully studied and cleaned; the Print is from a very old photograph, but even my photo taken to show her "saucy" face is a quarter century old:

The Louvre "Genetrix" has recently been beautifully studied and cleaned; the Print is from a very old photograph, but even my photo taken to show her "saucy" face is a quarter century old:

Note: The Greek Orders ought not to be shown only as columns, but this old drawing is good so far as it goes:

And the plans of the classical temples is genuinely useful, being pretty much to scale:

********

No comments:

Post a Comment