In Classical Greece and the Hellenistic

world, we were struck by the fact that the major artists seemed to address the

whole citizenry of the polis (city

state) and, after Alexander, secular patrons belonging to the class in power,

economically or politically.

Classical art clearly is addressed to urban, comparatively well educated

citizens, but to all of them, and, like the Greek drama, it is also accessible

to those who may not appreciate its finer points. The artist, for the first time, thought of himself as a

philosopher, to the extent that he too expressed his principles in written

treatises, and there is no evidence that his theories were not seriously

regarded. Change begins in the

Hellenistic period, in as much as public art as dynastic propaganda tends to

become readily accessible to the widest possible spectrum of the public so as

to be effective for that purpose.

Roman public art carries further the priority of the message, over, and

sometimes at the expense of, art for art's sake; not surprisingly neither

Hellenistic patrons nor Roman patrons regarded the artist as an intellectual, a

"philosopher", or, as we should say, as a unique creative

individual. There is some evidence

(as when the emperor Hadrian turns to sculptors from Asia Minor, seeming to

regard them as "real" artists) that in the Greek-speaking world, in

the largest cities, artists continued to be regarded more as creatively gifted

individuals than in the Latin-speaking West. Likewise, until Theodosius closed the Schools in Athens,

cities like Athens continued to be regarded as places where learning was

pursued for its own sake, even after the Heruli, a Germanic tribe, ravaged the

city. It is not true that Jews and

Arabs had no use for art; it was the possibility of image-worship that they

abhorred, and, just as Solomon had turned to Phoenicians to adorn his temple,

so in the eighth (Christian era) century the Great Mosque at Damascus drew on

Byzantine skills. The Early Christians

really did have little regard for art, but when Christianity became the

religion of an empire (and, in the West, the only stable, continuous source of

organized authority in the sixth century outside the area ruled directly by

Justinian), with the same reservations about the risk of image-worship, they

took over and developed what remained of the traditions and workshop techniques

inherited from Greco-Roman Late Antiquity; where the craftsmen were

Christianized "barbarians"--Franks, Saxons, and the rest--they

brought to their work much of their own traditions and their own mind-set, with

remarkable and fertile results. In

the Greek-speaking east, many of the artists were still urban professional

artisans, while in the west, wherever cities and towns reverted to mere

villages and fortified castles replaced towns, professional continuity

dependent on apprenticeship and markets disappeared. In both east and west, something entirely new developed: the

spread of Greek, Syrian, Egyptian, Irish, and Benedictine monasticism led to

the monasteries being the primary centers for continuity of learning and

artisan training. In other words,

for the next few centuries a great deal of the art that we study will have been

made by monks or lay brothers living the rule of one or another monastic

Order. They made art for the

ruling class as well as for the church (they also supplemented the agricultural

basis of their monastic economy by manufacturing, including making arms and

armor), but their finest efforts were acts of worship in material form: church

art. Furthermore, the Greek and

Renaissance and Modern (and Chinese and Japanese) idea of the artist as genius, a Latin word meaning that he is

a creative individual inhabited by a special

spirit, in Latin a genius, is

radically incompatible with Christian monastic community ideals. It is for this reason that we are so

interested when artists in the "high" middle ages, the twelfth and

thirteenth centuries, sign their names to their work or write treatises about

the churches that they have designed and when we see that increasing numbers of

artists and artisans are secular townsmen rather than monks or nuns. It means that the seeds of urban and

secular culture, which will produce the Renaissance, are in fact germinating

and multiplying precisely in the period when church-centered Medieval art

attains its greatest perfection.

As to the question of the audience for which the art was intended, the

answer is not simply that church art was the Bible of the

Unlettered. In the monastic

churches, abbeys and priories, the art was not by any means only for the

unlettered lay brothers and the populace who came to the greater monastic

churches on the major feasts of the church year; learned abbots expended great

learning on their design and often indulged their own theological ideas. Like the Greek Parthenon, however, this

high art was accessible also to the unlearned. Like Roman Imperial propagandistic art, however, it was

tightly controlled from the top; it was part of policy; it was (in our terms)

State/Church-controlled Media. On

the whole, monastic art is rather more communal, even though the religious

orders were highly hierarchical, than the religious art produced for lay

parishes. There is almost no major

serious non-Church art until near the end of the middle ages--no "Dying

Niobid", "Winged Victory" type of public art.

Justinian

(527-565), although Constantinople was his capital, was the last emperor to

speak Latin as his cradle tongue.

But, even later emperors who were Thracian or Syrian by ancestry as well

as Greek, and all of whom were Greek in language, called themselves Rhomaioi, Romans, and regarded the Holy

Roman Empire in the West as merely a Germanic kingdom. Justinian recaptured much of Italy and

North Africa from the Goths and placed his exarch

at Ravenna, south of Venice.

Charlemagne also regarded Justinian's Golden Age (which we call Early

Byzantine) as Roman; wishing to revive the Roman Empire when he was crowned

emperor by the Pope on Christmas, 800 A.D., he turned largely to the law and

literature and art and architecture of Justinian. It looks as if the memory of pre-Constantinian Rome had

receded into the mists for Charlemagne and his advisors, among whom were the

most learned, monastically educated men of his time. The German Otto II in the tenth century was similarly

inspired in seeking a Byzantine princess, Theophano, as his empress. When we shunt off Byzantine art and

history as a mere footnote to Late Antiquity quite separate from western

Medieval history, we are refusing to regard the eastern empire as the kings of

the west themselves regarded it, as the seat of continuity and urban life, as

their only bulwark against the further spread of Moslem princes' power. This did not prevent growing differences

from developing both in religion and in politics. Communications were too infrequent, trade was interrupted,

the Mediterranean Sea was unsafe to sail.

The sixth

century was a great age of church building in the Greek-speaking world. In little peninsular Greece alone,

excavators have found many dozens of good-sized, handsomely planned basilicas

of the Greek rite floor plan, like S. Apollinare in Classe at Ravenna and St.

Demetrios in Salonika (Thessaloniki), and there are just as many in Syria and

Asia Minor. Wherever the walls

have survived, the mosaic pictures are of high quality and great interest. Some of the icons are still in the

ancient encaustic technique. Early

mosques, as at Damascus, proliferate within a couple of generations after the

death of Mohammed (570-632).

Meanwhile, far away in England and Ireland, a century after the death of

St. Patrick and two centuries after the Anglo-Saxon invasion, most of the

monasteries founded by the Irish have become Benedictine and the Anglo-Saxon

kings' subjects have absorbed and begun to digest the British Isles' mixture of

Celtic, Roman, Anglo-Saxon, and Rome-directed Christian traditions. In art, the consequence is a stylistic

complex of great beauty that no one could have predicted. Critical to its formation is the

combination of exquisite craftsmanship based in decorative arts with the

Mediterranean Christian tradition based in the Greco-Roman world. A similar intermingling of disparate

cultures produced new art also in Germany and Lombard North Italy; Scandinavia

was only on the verge of being Christianized. It is against this background that the valiant attempt to

represent Charlemagne as a veritable Roman emperor, in an equestrian statuette,

must be seen, as well as his Palace Chapel by Odo and the Palace School of

manuscript illumination, collectively an extraordinary statement and an

extraordinary effort by a Frankish king.

The art of the

German Ottonian emperors in the tenth and eleventh centuries, continuing much

of what began with Charlemagne's dynasty and with its Byzantine connections,

taking advantage of the end of

Barbarian migration and some increase, therefore, in prosperity, represents a

culture that bridges over from the Early to the High Middle Ages. The human feeling and formal discipline

of the art anticipate Romanesque arts of the end of the eleventh century. The Norman duke William conquered

England with the Battle of Hastings in 1066: the Normans (Norsemen) are no

longer Viking invaders and indeed bring their French language to England. It is therefore worthwhile to look at

one English, pre-Norman church contemporary with Ottonian Germany. [There are fine examples of

architecture in Italy, France, and Spain, also, in the tenth century, but their

study is somewhat too difficult for an introductory course.]

*****

Justinianian

[K 12] In some respects, and those are

characteristic of Byzantine art as a whole, the Diptych with the Archangel Michael is more continuous with and

faithful to the ideals of the Greek art from which it sprang than the Diptych

of the Symmachi and Nicomachi more than a century earlier. Although the body of the archangel

seems rather insubstantial (but less so than you might think, considering that

archangels are supposed to be asomatoi,

bodiless), it has nearly perfect contrapposto

(except that the supporting leg is not directly under the head) and the drapery

follows, obeys the lines of the body perfectly logically; also, the wings are

like real birds' wings, and the hand holding the orb is effectively

foreshortened. The archangel has

none of the curious inconsistencies of the "Priestess of Bacchus" of

the Symmachi. On the contrary, the

inconsistencies in this work are deliberate, like the insubstantiality of the

gold architecture in the mosaics of the Rotunda of St. George: the archangel is

both in front of and behind his architectural framework, which is unrelated to

him in scale. It is deliberately

otherworldly, but it remains in touch with the intellectual and logical bases

of Greek art. The same must be

said for most of Byzantine art from Asia Minor (or by artists sent from

Constantinople) or from the Greek peninsula for the next thousand years. The Archangel Diptych is technically of

the highest quality. The

inscription says, "Receive him/that which is Present, and learn the

Cause/Reason" (the rest of the statement was on the other, missing leaf of

the diptych).

[K 212]

[1604] Equally Constantinopolitan

are two famous books (codices, plural

of codex, a book make of pages) with vellum pages, dyed purple (murex shell,

imperial purple) and written in silver, now tarnished to black. The purple probably means that they

were imperial commissions. Both

are in Greek, one of Genesis, the

other of the Gospels, for use in

reading the Lessons at the liturgy in church. Both have unframed pictures like the illustrations

for books like the Iliad written on

scrolls (rotuli), but the latter were

pen-and-ink drawings with limited added color. Full-color, painted illustrations that are unframed tend to

float on the purple ground, and the narrative necessity of a bridge or a tree

can be awkward, so the choice to eliminate the context, the background, the

frame is significant, in concentrating attention on the figures alone. From the Vienna Genesis, we see

Jacob wrestling with an (unwinged) angel; notice and remember the drapery that

looks as if it were lifted up by an invisible wire (it goes back to windblown

drapery of ca. 400 B.C., via Roman

Victories and other decorative figures) and the conventional tree at the right

that looks like a leafy parasol.

Notice, however, also how easily the illustrator draws figures in motion

and implies bodies in drapery and skillfully highlights and shades them. There is a long tradition of

illustration behind him, and he is in possession of it. From the Rossano Gospels, we have

Christ brought before Pilate; in this illustration, Christ and the men bringing

him are in Greek drapery (himation),

Christ's being, symbolically, gold, but Pilate looks like a Late Roman/Early

Byzantine consul (see the Missorium

of Theodosios, the Diptych of Stilicho, and the Official from Aphrodisias in

the preceding section), and his attendants look like those we shall see with

Justinian in the mosaics at Ravenna, San Vitale. As we observed above, Justinian regarded himself as one with

the Roman Empire, so Tiberius's governor, Pilate, looks like one of Justinian's

provincial governors. Notice again

how the heavy clothes worn at court preclude the use of pleated drapery. These purple vellum books were always

rare, but books do travel, and the importance of Greek books of Scripture in

monasteries cannot be overstated.

Someone like St.-Hilaire of Poitiers (ca. 313-367), Bishop of Poitiers,

a Greek born and educated (his real name was Hilarion), a Doctor of the Church,

surely had Greek books with him in France. Also, when icons later were banned, illustrated books

remained.

Now we turn to the buildings and mosaics of

sixth-century Ravenna built when it was ruled by Theoderic the Ostrogoth (no

barbarian he, having been reared at the court in Constantinople, being

nominally a hostage) and after it was taken by Justinian's armies in the middle

of the sixth century. The

buildings are so important because, from Honorius (402) until 751 (when the

Germanic Lombards took it), Ravenna was the capital of the Western Empire

rather than Rome, and Classis, its port, was the home of the western

fleet. Because Theoderic adhered

to Arian Christianity and Justinian (of course) to Orthodox Christianity,

Ravenna has two each of several things: two Baptisteries, two Sant'Apollinare

churches (the second one is in Classis), but only one San Vitale.

[G 122] [B 27] [B 28] The church of Sant' Apollinare Nuovo is confusingly (since nuovo means "new") the older of the two basilicas here dedicated to that saint. It was built by Theoderic a generation before Ravenna was taken from the Ostrogoths in 540 by Justinian's famous general, Belisarius. The mosaics on the walls of the nave are perfectly preserved, but, under Justinian, were altered--to remove the figures of Theoderic and his court from the intercolumniations of the representation of Theoderic's palace at the west end of the south wall (we know it's the palace, because it is labelled "palatium"). The long processions mosaics represent martyr-saints each with his or her crown of martyrdom and palms of victory, and each is named. The men approach Christ enthroned, the women Mary with the infant Christ, who is offered the gifts of the Magi (whom we have already seen on the "triumphal arch" of Sta. Maria Maggiore and on the hem of the Empress Theodora's robe in San Vitale). Although the background is solid gold, the style and the general effect here is a little softer and less hieratic than in San Vitale; it is just as Byzantine, for, as we noted, culturally Theoderic was no barbarian. The column capitals are of a special kind, peculiar to this period, with acanthus leaves swirling around them, as if caught in an eddying wind, and notice the typical Early Byzantine trapezoidal impost block, between the carved capital and the springing of the arch.

[MG 166] [MG 167] [1612] Sant' Apollinare in Classe is a generation later, and its mosaics are contemporary with those in San Vitale, though not evidently executed by the same workshop of mosaicists. Its bell tower is typically Italian, built separately from the church like Pisa's most famous one, but it is a later addition. Typical of a Greek basilica is the faceted exterior (here semi-octagonal) of the apse and the separate rooms built on either side of it, just like those at San Vitale. Neither of these Ravenna basilicas has a transept, but the older basilicas in Rome, except for Old Saint Peter's itself, don't have one either. Inside, Sant' Apollinare in Classe shows us an open timber roof, such as Santa Maria Maggiore and Old St. Peter's once had and Greek basilicas in Thessaloniki and many other places in Greece, too. Here we have lost all the mosaics on the nave walls, but in glorious recompense the "triumphal arch" and apse mosaics are preserved. In the apse, in the center, the orans is Saint Apollinaris; Christ is represented not in bodily form but by the cross that is his glory superimposed on the star-studded vault of heaven, but in the center of the cross is a small head of Christ, bearded as in the Greek church. The conventional green landscape is Edenic, a sinless realm bathed in cool, clean light, not a visual but a spiritual landscape; the sheep are the greges, the flock of the congregation of the faithful. On the "triumphal arch", the sheep are the twelve disciples, coming from the gates of Bethlehem and Jerusalem (the clouds are the mosaic version of the same conventional clouds as we saw on the pictorial relief of the Sleeping Emdymion); above them is the bust of Christ, blessing (cf. K 175 in Section XIV, below), flanked by the symbols of the evangelists: Matthew (winged man), Mark (winged lion), Luke (winged ox), and John (eagle--winged by nature), with the same kind of clouds. These symbols, which we shall see now repeatedly for the four evangelists, derive from the vision of Ezekiel in the Hebrew scriptures (Ezekiel 1:10) and are only one example of Christian writing and art seeing the whole "Old Testament" (not "Old" to Jews!) as typifying and culminating in Christ ("Christ" is Greek for "Messiah", that is, Anointed).

[K 297] The Mount Sinai, St. Catherine's Monastery, Icon of the Madonna and Child

Enthroned with Saints is one of several early icons preserved there that

are in the same medium exactly as the Roman-Egyptian Fayum portraits studied

earlier: encaustic on gessoed wood

panels. Many must once have

existed; technique so fine as this is never a flash in the pan but in a long

tradition. But early icons were

destroyed during the period of officially sanctioned Iconoclasm (730-843), and

only the geographical isolation of this monastery preserved a few. The image is like a larger, finer

version of the style of the Rossano Gospels, or you could say that the St.

George shows us one of the courtiers of San Vitale, only softly, in paint, with

light and shade. The Madonna, too,

is gentle and human, and the colors are lovely.

Greek Peninsula

Greek Peninsula

Syria

[MG 238] Another regional school of

sixth-century basilica design is Christian Syria. Der Turmanin

shows the interesting features of the façade: twin towers with a tribune between them over the arched

entrance. There is nothing like

this in Asia Minor, Greece, or Italy.

The question is whether, with the spread of monasticism, not least from

Christian Syria, the idea of twin towers on a façade, such a standard feature

of medieval churches in France, had its source here. The answer is not certain, but sometimes it is just as

important to learn what is uncertain as to master rock-solid certainties.

[O 429] [O 433]

[O 434] Although its leafy

capitals and trapezoidal impost blocks and its timber roof remind us of the

foregoing, the Great Mosque at Damascus,

of the 8th-century Ummayad Dynasty, belongs to Islamic Syria; the world has

changed. As for Hagia Sophia, we

know the architects' names, `Abd-al-Rahman and `Ubayd B. Hurmuz, and its exact

dates, 707-715: Islam keeps good records.

A mosque is not like a church.

We are not looking at a nave and aisles but at the equal spaces between

rows of columns. It is not laid

out for liturgical worship but to bring together all the faithful of the region

for daily prayer and to hear the readings. It is laid out rather like an orchard or, you might say,

like a very great Arab tent with many poles. We also notice that the arches of the arcade are very tall

and, of course, the arches in the wall above are not a clerestory, since they

do not open on the outdoors, though they do let light through from the distant

windows. With the spread of Islam

to North Africa, part of Sicily, and Spain (cf. the Mosque at Cordoba at the

end of this section), Islamic design is not marginal to this course. The mosaics in the Great Mosque at

Damascus are actually the work of Byzantine (Greek or Syrian) craftsmen. That is why they remind us so forcibly

of Pompeii and Herculaneum. Their

date, ca. 715, falls within the period of Iconoclasm in the Greek church when

artists were underemployed for work in churches. Although nothing like them can be seen in Christian

churches, they would have found parallels in the Palace at Constantinople and

in public buildings, where the traditional refreshing images of landscape

architecture and idyllic settings were customary and appropriate. But for the Great Mosque, we might have

no evidence of work of this kind, in mosaic, at this level of skill, at this

date, although we see similar landscape in book illustrations in the 10th

century (see K 148 in the next section).

We now turn to the art of the 7th to 11th

centuries in western Europe.

[K 180] In 1939 the ship-burial of an Anglo-Saxon

king was discovered in East Anglia near a village called Sutton Hoo; you can see

its contents today in the British Museum in London. Nothing about most of the objects would tell you that the

king and his people were by this date, ca. 650, Christians: the great hanging

bowls are adorned with disks with Celtic designs in enamel (recalling the

Desborough Mirror and the Battersea Shield), the great solid-gold buckle

reminds us that the Angles and Saxons who came, traditionally, in 449 were

Germanic, and the purse lid has Anglo-Saxon designs that remind

us, further, that in their migrations, in the 4th century, the Germanic tribes

had been over north of the Black Sea, whence the rather Scythian-like bird of

prey, not to mention the hero between lions recalling the Sumerian motif on the

Philadelphia Harp from the Royal Cemetery at Ur! The ribbon interlaces,

which these artists combine with abstracted animals, possibly arose from Coptic

elaborations of guilloche border

patterns. Coptic? Egyptian? It would seem far-fetched but for the unifying phenomenon of

these centuries: the international spread of monastic foundations; possibly

Coptic monks, or church objects from the Coptic Christian world, transmitted

the germs of these motifs. The

church in its first millennium was truly katholikós

= universal: non-national. As for

the Christianity of the king buried here, it is attested by Anglo-Saxon (Old

English) literature and by the presence in the ship-burial of silver communion

spoons of Byzantine manufacture, probably from Constantinople. [At this time, and still today in the

Greek Church, Holy Communion is administered, wine and a bit of bread together,

from a special spoon]. We already

saw Germanic jewelry with cloisonné

[K 305]; here we have solid gold champlevé

with garnets in the cells.

[K 184] [K 185] In the Northumbrian Lindisfarne Gospels, from a monastery in northern England, and about a half century later, we also have the author page and the carpet page (our examples in this case both belong to Matthew). The carpet page here incorporates the Cross but otherwise is pure interlace, with and without animals, thus differing from the carpet pages in the Book of Durrow mostly in its more evolved intricacy: considering the work and the mind-set that went into all of this rational interconnectedness is mind-boggling. From scored lines visible in raking light on the vellum and from visible pin pricks scholars have deduced the use of a fine grid and an unwinding string compass as well as a rigid compass to create the pattern. The colors here are subtle and very beautifully harmonized. The author page, on the other hand, betrays (what in fact is documented in this case) the presence in these Northumbrian monasteries of copies of Gospel books from the Mediterranean world, from Rome (and, to judge from the use of the Greek word for "saint", written in Roman-alphabet letters, from the Greek-speaking world, too). It is not only that Matthew (o agios Mattheus) is represented straightforwardly as an author writing his book, with his symbol, the winged Man (imago hominis) tucked behind his halo; he is in three-quarter view, wearing an himation with (sort of) folds, seated on a (sort of) foreshortened seat, with a pleated curtain at the right. It is fascinating to see what the Anglo-Saxon artist does with such a prototype. He disassembles the seat and footstool, and he makes what were shadows in the folds of drapery into orange slivers on a green robe. It is as if the illusion of optical vision in his model made sense to him only in terms of its potential for pattern. He piously retains the traditional three-quarter view for Matthew but alters it to make it lie flat on the page and work with his decorative use of flat color.

[1616] The Irish Book of Kells is about a century later; it is the latest of the

great Hiberno-Saxon Gospels. From

the Book of Kells we look at the third kind of decorated page, the illuminated

initial. At Matthew I:18, after all the "begats", the parentage of

Christ himself is given, beginning in Latin with the words Christi autem. Here

the first gospel is given a second illuminated initial page that the

others don't have; it is traditional: using the Greek letters, a large chi and rho, X P, for Christi. Although the Book of Kells is the most

richly illustrated of all, it does not have such mind-boggling pure interlace,

because, as an Irish manuscript, it uses the repertory of Celtic motifs (the

whorls, etc.) much more than the Anglo-Saxon ones, and it adds to the purely

formal decoration all sorts of little animals and faces. The elaboration of illumination in

monastic manuscripts could go no further than this. The Book of Kells also has the evangelist

"portrait" pages and throughout its text, wherever there is space at

the end of a line or section, delightful small, whimsical drawings. They are loving adornments without any

particular reference to the text of the gospels.

[K 240] After centuries of Roman colonization

in the western half of Germany, the

horse and rider on the stele found near Hornhausen may reflect acquaintance

with provincial Roman images of riders; indeed, it probably does. But as with the Anglo-Saxon version of

a draped figure in 3/4 view (the Matthew of the Lindisfarne Gospels), here the

Frankish (do not equate "Frankish" with "French" in the

modern sense of the word) artist has thoroughly negated three dimensionality by

means of the double outline around the horse. Also, he felt no need to provide enough space behind the

shield for us to assume the rider's body there. And, of course, at the bottom of the stele, we see the same

kind of animal interlace as in the contemporary Lindisfarne Gospels, only

carved instead of drawn and painted.

[K 241] Early Medieval churches had the area

around the altar surrounded by a stone fence, usually carved (in Rome, the

church of Santa Sabina, a 5th-century basilica, still has one). The Balustrade of the Patriarch Sigvald in the Baptistery of Cividale

Cathedral in northern Italy is Lombard work. The Lombards (a Germanic tribe whom the Italians called

Langobardi = Long Beards, the tribe that took Ravenna in 751) had some

acquaintance with Early Byzantine church art, and the basic layout of the

Sigvald relief, the cross with trees and candlesticks, for example, is

Byzantine; placing the animals in wreaths and the tree of life guarded by

griffins came from the same source but reflect Byzantine use of motifs from

Sassanian Persian weaving and metalwork.

The "chip" carving here is cruder than chip carving technique

in Byzantine work, and the contours of the figures are cooky-cutout (remember

the stelai in the Grave Circle at Mycenae). The Symbols of the Evangelists, of course, are the same Man,

Lion, Ox, and Eagle that we met first in Sant' Apollinare in Classe. This is a splendid example of

Mediterranean and Germanic arts just beginning to coalesce.

[K 243] The North Germanic (Norse) Vikings ca.

800 A.D. were as yet hardly touched by Mediterranean religion (Christianity) or

general culture, although the Eddas do make their gods, the Aesir, descendants

of the Trojans! Books, at least a

few, had, as usual, travelled. On

the other hand, the written Eddas are later than the Animal Head on a Post from the Oseberg Ship

Burial. This Viking art is

later than the Lindisfarne Gospels or the poem Beowulf, about contemporary with the Book of Kells, but earlier

than Norway's famous wooden (stave) churches. The Norse version of animal interlace is very flat with

evenly spaced ribbon elements. The

ancestry of the dragon head is as complex as that of the creatures on the purse

lid from Sutton Hoo.

CAROLINGIAN ART

[K 249] Artistically, culturally, the Bronze Equestrian Statuette of Charlemagne

from Metz sums up everything that in Europe west of the Saale River,

excluding Brittany, Spain (which was part of the Ummayad Caliphate), and the

British Isles, distinguishes the Carolingian Empire from the Merovingian

kingdom that preceded it. The

horse's head may be small in proportion and its legs rubbery, but compared with

the Hornhausen horse it is a miracle of Greco-Roman naturalism; so is the treatment

of drapery in Charlemagne's cloak.

Small as it is, for those who made it, it must have evoked very

powerfully imperial images like the equestrian Marcus Aurelius which then stood

near the Lateran Basilica, the Cathedral of Rome. It proves (however the goal was accomplished) that

"research" into the Roman past was not confined to monastic scriptoria.

[MG 200] It is not often that we can learn most

about architecture of a certain kind in a given period from buildings that

never got built as planned (and in any case have been replaced long since by

newer buildings). Such is the case

with the table-top size Plan for a

Benedictine Monastery at St. Gall of A.D. 820. Besides the plan itself, drawn to scale (the module is the

length of a bed in the dormitory) although without wall thickness, we have all

the descriptive labels (written in verse meter in Latin, in the legible

Carolingian book hand that is the basis for our printed fonts) on the plan (not

included in the copy from which your Print is taken) to tell us which building

is which and what was in the upper storey of two-storey buildings (around the

cloister). Further interpretive

information is in the Rule of the Order of St. Benedict, the only monastic Rule

that is published and thus available to laymen. There is so much to learn from the St. Gall Plan that a

whole course can be based on it.

Here we shall only notice what we need to know for this course. The abbey church, the cloister, and the

abbot's house were built of stone, but needed steeper roofs (to shed heavier

snows) than in Italy. The church

has two apses, for altars to SS. Peter and Paul; so have some later ones in the

Rhineland. The scriptorium (St. Gall was an important

center of book production) is in the upper storey of the square north of (left

of) the choir. We saw a choir in San Vitale, but not in the basilicas in Rome; now we see a

church with a transept (deriving

straight from Old St. Peter's) and a choir between the transept and

apse. The church has many altars,

because every Benedictine abbey had members who were priests as well as lay

brothers (who, like nuns, were not), and priests all must say Mass daily. The twin towers, with spiral

staircases, at the west are built separately and held bells. West of the abbot's house is the

School: any child who was educated at this period went to a monastic school

(although a royal child might have tutors instead), and west of that is the

Guest House for Distinguished Visitors

On the south side of the western apse is the Guest House for Commoners;

the Guest House for Distinguished Visitors has a necessarium naturæ, an

outhouse, but the Commoners' hasn't.

The School, the Abbot's House, the Doctor's House, the Infirmary, the

Novitiate, and the Monks' Dormitory all have necessaria naturæ; in the

corner of the Monks' necessarium is

(labelled) a lucerna, since the Order

of St. Benedict specifies that a lamp must be left burning there at all

times. Some very clever bits of

planning here go beyond the requirements of the Rule: the Infirmary and the

Novitiate each has its own chapel (at this date, novices were young boys, not

ready to share fully in monastic life), but the architect has them built

together, double-ended, with a dividing wall, each entered from its own

cloister; the doctor's house, herb garden, and leech house are near by. South of the Novitiate is the Orchard

(each fruit tree labelled) sharing its plot of land with the Cemetery, then the

vegetable garden, then the hen house and goose house with a dwelling for their

keeper between them. Between the

main cloister and the perimeter wall is the Industrial Area: barrel makers,

sword and armor makers, goldsmiths, leatherworkers--everything needed and some

to sell. At the west are all the

barns, marked according to the animals to be kept in them. The Monks' Cloister, finally, which is

rather like the peristyle in a Pompeiian house, is attached to the south side

of the church (the church was 200 feet long). The dormitory has a door into the south transept, since

Benedictine monks must rise to sing an Office in the wee small hours; the Cellar

has large barrels for wine and small kegs for beer (water was iffy to drink,

and the Rule allows a pint of wine apiece, daily); even without its

inscription, the Refectory is recognizable from its long tables and has

passages to kitchen, bakery, and brewery.

Notice that such passages connect all the parts of the layout that are

part of the monks' Enclosure; the agricultural and industrial personnel, as

well as school boys and visitors, had no casual access to the Enclosure. It is thought that most of the

buildings were of native timber-frame construction, just like barns and

workshops, et al., outside of monasteries in this region.

[MG 185] The Abbey Church of St. Riquier at Centula, completed in 799, no longer

stands. It is known from a drawing

in an 11th-century manuscript (now lost), copied in an early 17th-century

Benedictine printed book. Thus we

know its elevation (its vertical

projection), whereas for St. Gall we knew only the plan. With narthex, nave, transept, choir,

and apse, its plan resembles St. Gall except that the narthex is

designed like a second transept but unlike the transept it is in two storeys

with groin vaults supporting the upper floor (where you see Xs, there are

groins), and there are four towers with spiral staircases attached

flanking the choir and to the west façade: note the arched niche fronted by two

columns between the west columns--above the niche the wall is flat; this makes

a distinctive two-tower façade, the lineal ancestor (whatever the

possible relevance of churches like Der Turmanin) of all the western

two-towered church façades.

Germans have a convenient name for this, which we all use: Westwerk. But there is more which is unlike Rome's basilicas that we

must learn here. Where the

transept and the transept-like narthex cross the same-widthed nave, the crossing squares thus created are framed with arches, which support crossing towers. No early

church in Italy has a crossing tower.

The drawings show round crossing towers here; the transition from square

to round cannot be ascertained since the church no longer stands but was more

likely, perhaps, a squinch (see

below) than a pendentive. From the

drawings, also, it is thought that the spires

of all the six towers were open and wooden, as your drawing shows. What is quite certain is the wholly new

shape of the Centula church (near Abbeville, France). Besides having the necessary steep roof, its design is

insistently vertical: it is the cumulative effect of Westwerk, tall narthex/transept with spired crossing tower, tall

transept with spired crossing tower, two more slender towers, and even an

extra-tall apse. We take churches

with "aspiring" proportions for granted, but this is where it all

starts; all the basilicas of either Latin or Greek rite are

fundamentally horizontal buildings.

Perhaps the necessity of a steep roof combined with knowledge of the use

of domes over central-plan churches inspired the northern builders to create

these innovations.

[K 308] The Grandval Bible represents the Carolingian School of book

illumination located at Tours and a generation later than Charlemagne's own Palace

School manuscripts. Here we have

illustrations to Genesis 2: Adam and

Eve. These are copies of

illustrations in a Bible made in Italy in the 5th century, not much later than

the Vatican Vergil. In the narthex

of the church of San Marco in Venice the mosaics in one dome are also copies of

just such a Genesis. It had framed pictures with Late Roman

landscape elements and short figures recalling those in the Parting of Lot and

Abraham on the nave wall of Santa Maria Maggiore; just as Christ was beardless

in 5th-century art in Italy, so here even God the Father is beardless (very

strong evidence in itself that the model was a very early Latin Bible). The sky is horizontally striped in

blue, lavender, pink; these stripes derive from optical-illusion skies where

the artist observed that only the high sky looks blue and it shades to white or

pinkish at the horizon. Eve

nursing Cain in a rustic bower while Adam delves (as a consequence of that

apple, in the register above) has, even in the Carolingian copy, much of the

childlike charm of 5th-century western art. The storytelling is direct and literal.

OTTONIAN ART

[K 254] How very different is the portrait of

the Emperor Otto II (or III) receiving

the homage of the Provinces from the Registrum Gregorii, an Ottonian

manuscript book of the late 10th century!

If this is Otto II, he is the emperor who married the Byzantine

princess Theophano, and Otto (whichever) is represented very similarly to

Theodosius on the Missorium in Madrid or on the base of the obelisk in

Constantinople, even to the way the raised knee is handled. But this is almost exactly 600 years

later. The Homage of the Provinces

goes back at least to the Roman emperor Hadrian (we have reliefs of provinces

from the temple built to honor him when he died in 138). Stylistically, there are real changes

from Carolingian drawing. Not only

is the style of drawing more disciplined than before, even in the Palace School

manuscripts, but it is a different kind of discipline, emphasizing clarity of

contours, some of the smoothest contours we've seen since Egyptian art. These contained forms are especially

characteristic of the Trier-Echternach School. The frontality, not so much of the central figure, but in

the relationship of the whole composition to the frame and the surface, also is

a change from Carolingian style.

This work, where it relates to Byzantine work, relates to Middle

Byzantine, with which it is contemporary, right after the end of Iconoclasm,

rather than to the past--Justinian's Early Byzantine. From that source surely comes the preferred color tonality:

cool and predominantly pale, what we think of as pastel or sherbert colors,

favoring the secondary hues, green, orange, and violet, more than previously.

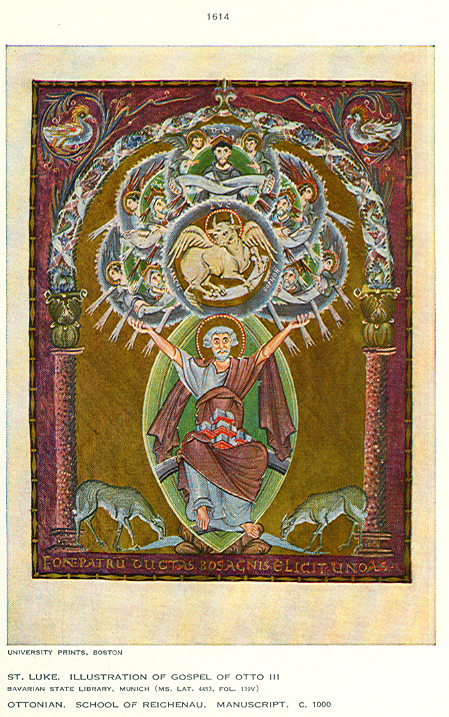

[1614] Although the Reichenau School, way up

the Rhine (Reichenau is a perfect place for a monastery, being a tiny island in

the Untersee part of Lake Constance, where modern Germany, Switzerland, and

Austria meet), has a livelier manner of drawing than Trier, it shares the new

discipline and the lavender and green color combination. The Codex Aureus (Golden

Book--and on purple vellum) of Otto III, ca. 1,000 A.D., is a splendid imperial Gospels. Here we have the portrait page for

Luke, rather than Matthew, both author portrait below and evangelist symbol

above, the latter surrounded by the heavenly host, with a prophet as an

antetype for Luke at top center; all this is framed in a living arch on

purple-mottled columns, with exuberant leafy capitals no longer really

Corinthian. The explanation is

written in a metric line of Latin at the bottom: FONTE PATRUM DUCTAS BOS AGNIS

ELICIT UNDAS = The Ox (Luke) brings forth waters (note the sheep

slaking their thirst at the bottom) drawn

from the Source of the Fathers

(i.e., from the Hebrew patriarchs and prophets, asserting that Christ is the

Messiah foretold by the Hebrew scriptures). This is truly an elaborately worked out picturing of Church

theology. The objects in Luke's

lap are codices of his Gospel.

[K 291] The Gero Crucifix from the time of Otto II, ca. 975, now in Köln

Cathedral (begun 1248), not only possesses the discipline and clear contours

that we have seen in the foregoing, but it is nearly lifesize, carved of wood,

joined at the shoulders, gessoed and painted, the colors still discernible

after more than a millennium and concomitant generations of candle and incense

smoke. Still more important is

what it is and means. There has

never before in western art been a Christ on the cross like this one, which

emphasizes his humanity and suffering.

Indeed, for the first thousand years of the Church images of the

crucifixion of any kind are few and far between. The best comparison is with the

Crucifixion at Daphni [K 230; see next section] about a hundred years

later. The art of the early Church

tended to deemphasise the painful and degrading side of what, as they knew, was

the most disgraceful form of capital punishment and too, too mortally

human. Only approaching its second

millennium does the church, and the whole body of the faithful, gain the

confidence to consider that Jesus' very glory came through his acceptance of

the cross--a precondition, after all, of his Resurrection and of Christians'

salvation. The Gero Crucifix is

evidence of Christians' reaching this stage of spiritual maturity. In the history of medieval art, as a

nearly lifesize masterpiece, even more powerfully expressive than one with

"correct" anatomy, it is one of the first signs of the rebirth of

substantive (full-size) sculpture, which will flourish a century later in the

West.

[MG 38] Also in Köln and of the same generation

as the Gero Crucifix is the Church of St.

Pantaleon. Its Westwerk is

original, and we now see why we took the trouble to describe the Westwerk of St. Riquier (Centula) in

some detail: in plan, this one would look almost exactly like it. In fact, Ottonian architecture grows

directly out of Carolingian architecture, only it is less tentative, more well

thought-out, after nearly 200 years' experience, and it has some new

details. On the Westwerk of St. Pantaleon, for example,

the rows of little arches under the string courses combined with the narrow

strips on the corners and between the windows, here built in stone, derive from

the brick work of Lombardy, which is, after all, part of the Ottonian

Empire. Köln is famous not only

for its Gothic Cathedral but for its early (Ottonian and Romanesque) churches.

[MG 199] [MG 198] St. Michael's Church in Hildesheim (1003-1033) took a direct hit from a bomb in 1945 in World War II. It has been lovingly rebuilt. Even the wooden ceiling which had fine 13th century paintings on it (totally lost) has been painstakingly restored and repainted, working from photographs. Small consolation (since it could have been done without the sacrifice of the original fabric of the church), but, in the process of study to rebuild it, excavation and the removal of some later additions brought to light new evidence for the original design, so that a better plan and exterior elevation can be drawn today than the one on the Print. Looking either at the plan or the view down the nave, we see that Hildesheim has double apses (like the church on the St. Gall plan) and crossings and a choir (like St. Riquier), and, as in the latter, the plan is based on the crossing square used as a module. But it also has alternating supports like St. Demetrios in Thessaloniki! These make it explicitly clear that the nave is exactly three crossing squares in length, and, considering the Byzantine connections that we have noticed, it may well be a borrowing from Byzantine basilica churches. Only, since St. Michael's has no gallery (second storey) above the aisles, but a flat nave wall like previous western churches, the square piers cannot continue up vertically. The zebra arches here are probably inherited from Carolingian practice, whereas in the Palace Chapel at Aachen they were a fresh borrowing from an early mosque, like Cordoba.

[MD 35] The

Bronze Doors of Bishop Bernward of Hildesheim are not exterior doors but

lead to the crypt of St. Michael's (which, incidentally, is not the

Cathedral of Hildesheim). Bishop

Bernward not only had St. Michael's built but was a scholar, and he went to

Rome, where he saw Trajan's column and basilicas with bronze doors (Santa

Sabina has wonderful 5th-century doors, but they are of wood). He returned and had cast a paschal

candlestick in the shape of a spiral column, but with the life of Christ

instead of Trajan's Dacian Campaigns figured on it. It seems strange to us today for a great ecclesiastic and

scholar, but Bernward is reported to have been also a fine craftsman and bronze

caster. He has to have been, for

these bronze doors which were made (the inscription lets you read the date

plainly, MXV) in A.D. 1015 are the first bronze doors cast in one piece

since Roman antiquity, about 700 years earlier (calculating from the completion

of the Basilica Nova of Constantine).

The doors have lions' head pulls (rings in lions' mouths), which

Bernward surely saw in Rome (the earliest known examples go back to the 5th

century B.C. in Greece); of course, the Ottonian lions' heads prove that the

sculptor was not familiar with living lions. The leaves of the door, valvas,

have Old Testament stories on one, the Life of Christ on the other--recalling

the north and south nave walls of Santa Maria Maggiore: from the Fall to the

Redemption is the idea. The scenes

in the panels could easily have been adapted from pictures in an illustrated

Bible, although with compositions different from those in the Grandval Bible,

but in any case we have here an artist fully capable of creating his own

narrative drama in eloquent speaking gestures. God: Why did you eat of it? Adam: The woman gave it to me. Eve: The Serpent said we should eat it. It could not be more economical or

vivid. The 3/4 views are handled

skillfully; what might be a fault in a less expressive work, the shortening of

God's arms, here only enhances the sense of his shoulders hunched up in

outrage. The plant life necessary

to indicate the Garden of Eden most certainly came from book illustrations; now

you see why we have taken the trouble to notice every conventional tree we came

across. Artists in the Middle Ages

do not look at trees in order to draw them but only at models in pre-existing

pictures. E. R. Curtius in his

famous book, European Literature and the

Latin Middle Ages, pointed out that poets, similarly, did not (until the

13th century) look out their own windows at the Springtime but took Springtime

phrases from the poets of Antiquity which they adapted for their own verses,

even "smelling" trees that didn't grow within 1,000 miles of where

they lived.

[G 364] Early Medieval architecture is not

confined to France and Germany--not by any means--but we can only consider one

example, from Late Anglo-Saxon England, the Tower of the Church at Earl's Barton. Subtract the clock and the battlements at the top, both

Victorian, and the rest of the church, which is every stage of Gothic. Here, a century and a half later, is

the English counterpart to the Lorsch gatehouse (with little arches and

vertical strips as on St. Pantaleon--but very differently rendered, being much

farther from their Lombard origin).

The little arcade near the top has column shafts shaped just like fat

cigars, and here too the use of angular shapes for arches reminds us of

half-timbering. In fact, beside

the Anglo-Saxon church tower, the Lorsch gatehouse, apart from its colored

patterning, looks downright Roman.

After the Norman invasion in 1066, church architecture in England will

be a regional extension of the Norman architecture of northwest France, just as

Old English will give way to half-French Middle English. Yet the Earl's Barton tower is certainly

well built, to stand a thousand years.

[G 431] Repeatedly we have mentioned the

Ummayad Caliphate's great legacy to Spain, and to Europe, the Mosque at Cordoba. Like the Great Mosque at Damascus about

a century earlier, it has leafy capitals with trapezoidal impost blocks

arranged in rows to support tiered arcades. Only here, as promised, they are zebra arches, with

alternating dark and light voussoirs. We have already seen that Carolingian

and Ottonian architects found this attractive. Notice besides that here the tall arches nip in at the

bottom, as if continuing the line of the circle; thus they are slightly

horseshoe-shaped, and some Romanesque architects will adopt this

horseshoe-shaped, more than semi-circular arch.

No comments:

Post a Comment